Trivia Crack is a competitive trivia game developed and published by Etermax in 2013. Initially, the game launched for iOS and Android but would later become available on other mobile platforms. Its color theme and light subject matter make it accessible to kids and older. The game shares some key mechanics with my team’s game (tentatively titled Braniacs) as players are expected to sift reasonable sounding falsehoods from the crazy truth; however, its dynamics of deceit contrast by being generated by a computer rather than other players, and the multiple players in Brainiacs can either offer meaningful insight or tell conniving lies.

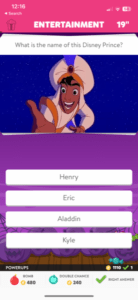

Trivia Crack relies on multiple choice; the game will ask a question, and the player has four options to choose. Like classic multiple choice on the SAT, some of the options are definitely off, some sound very reasonable, but only one can be correct. Due to the vast bed of trivia in the game, however, it’s very possible the player will have absolutely no idea the answer. In cases where my expertise, I exercised some deductive reasoning skills that were relatively reliable (but not all the time).

The key aesthetic then is characterized by uncertainty, pensive thought, and resolution to uncover the truth. This is similar to the desired aesthetic of Brainiac, as the underlying mechanics and dynamics share parallels. In Brainiacs, one player reads a claim, and it’s up to every other player to determine if the claim is true or false. Abstractly, this reduces to a multiple choice problem, except there are only two choices. A slight difference, however, may be the reaction players have when settling on a decision. There’s a sense of “oh, well there were many options, I was likely to pick the wrong one” in Trivia Crack. However, with only two choices, I saw players get particularly excited during playtesting since the right answer was often the answer they didn’t pick. This instills the “if only I had switched” mentality, which adds to the mind games. This effect is particularly meaningful since “mind games” are the key distinguishing dynamic of Brainiacs to Trivia Crack.

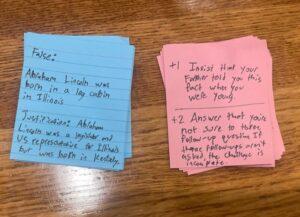

The mind games arise from a potentially unreliable argument maker. Trivia Crack will never “lie” to you exactly. It will ask a question, and some sound reasonable, but any misleading that occurs is a result of player ignorance or overthinking. When the claim maker in Brainiacs makes a claim, they could purport it to be true or false, whatever potentially suits their advantage the best. Deceit is further incentivized by the challenge card the claim maker draws, which may give bonuses for lying. Further, there are elements of “groupthink” at play since other players are freely allowed to discuss the truth value of the claim as well. If more players vote one way, an uncertain voter may give into peer pressure…potentially falling for a convincing argument that isn’t based in truth.

Furthermore, the greater number of players adds a lot of dimensionality to the domains of knowledge at play in Brainiacs over Trivia Crack. Playing Trivia Crack, I’d always get excited when I pulled a science or history question. Those are beds of knowledge I’m relatively comfortable with. But when sports was the category, I sighed in anguish. The playtesters in Brainiacs had similar dismay when the claim was outside their specialized knowledge. However, multiple players offered diverse knowledge. One player didn’t know much to answer the question on Pokemon, but another more seasoned Pokemon player was able to provide some context. As previously mentioned though, the mind games underlie any exchange of information, and since players vote simultaneously, a conniving player could be lying through their teeth.