Hot Take: The Game (not to be confused with the game Hot Takes) was designed by Jonathan Cresswell. In its current form, it only exists online (hottakegame.com) and only requires one internet device to be played. It seems to be geared towards people who like arguing and are on the internet–probably 16-60 year olds.

The high level concept of my team’s game, Yap Battle, is similar to Hot Take in a number of ways: it involves making an argument around silly topics while trying to incorporate specific, hard-to-slip-in words (I’ll call these “keywords” in this post, borrowing from Hot Take). While the extremely simple mechanics of Hot Take are easy to learn, yielding generally fun and entertaining play, I want to avoid replicating some of the emergent dynamics and aesthetics. There are two specific problems: firstly, the rules and scoring allow for a strategy that goes against the game’s concept. Secondly, the mechanic responsible for keeping the arguments in check can lead to an either mean-spirited or too lenient aesthetic.

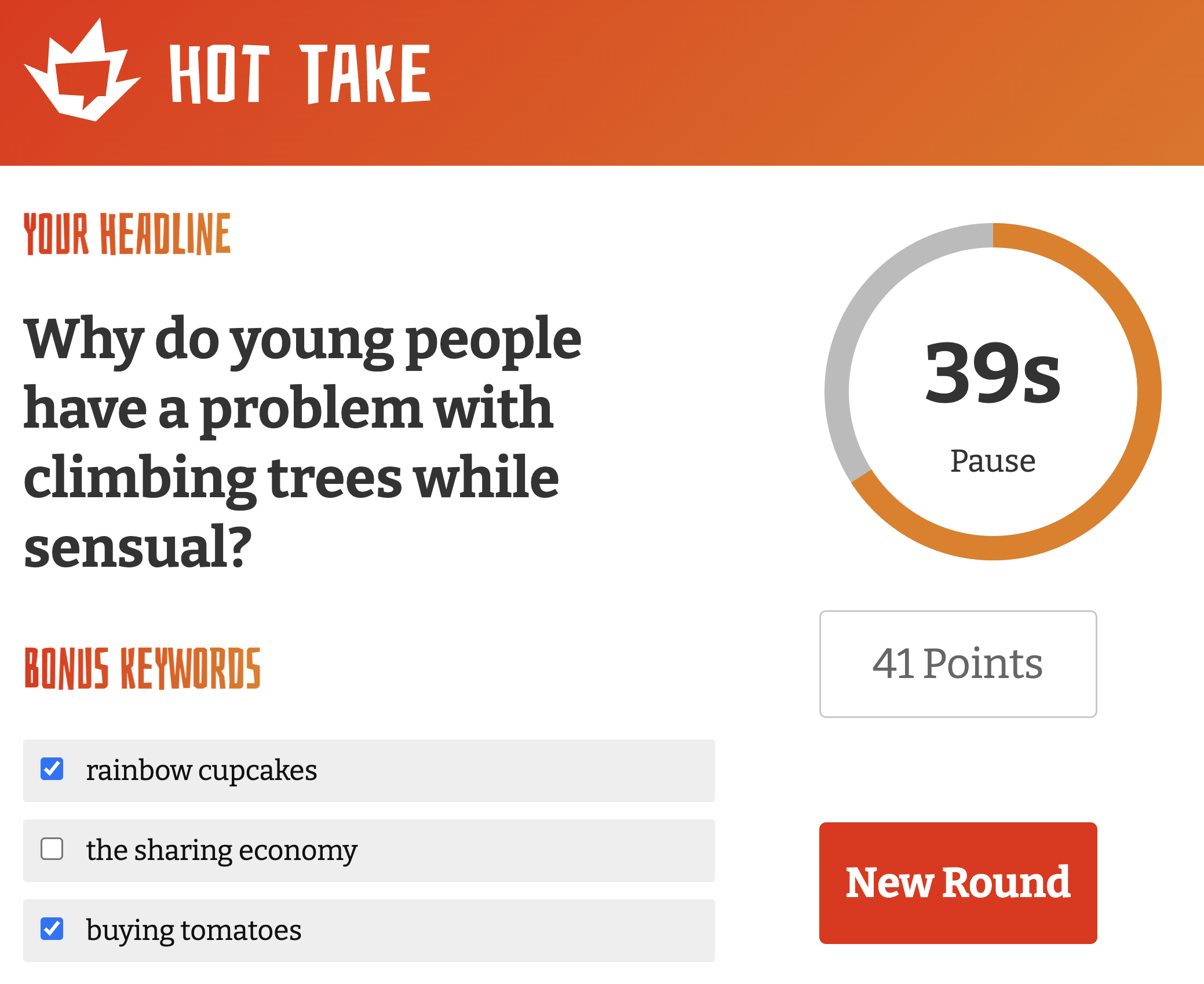

In Hot Take, the scoring only has to do with how long a player is talking and how many of three keywords they can slip in. The mechanics of the score do not by themselves encourage the player to talk about the headline at all–this is encouraged by the fact that other players can stop them mid-speech if they are off-topic or pause for too long. If the “editor” for that round agrees, that player’s turn is over.

When playing with my friends Nick and Samantha, I noticed that there was nothing encouraging me to make a good argument defending the headline. As long as it seemed like what I was saying was related to the headline, I could blab on. I could contradict myself and repeat myself to fill the time. I could make wild lies, lazily incorporating the keywords without good justification. Not only were these strategies valid based off of the rules, but they were encouraged by the scoring system.

Of course, while these strategies were possible, I generally stuck with the spirit of the game and made my arguments as comprehensible as possible. However, for our game, I don’t want to rely on people’s good nature–and we don’t have to. In our game, two people debate against each other and the others vote for who they think won. The winner gets points. This encourages people to keep their arguments on topic and comprehensible. It also encourages tying in the “keywords” more seamlessly. (We also have another mechanism for this, which is less relevant to this comparative analysis.)

The “stop speaker when they’re off-topic” rule has other downstream effects. It wasn’t always easy to know when to stop another player. It might seem like they’re off topic for a bit, but I found that no one called them out, it was more fun because you got to see how they were going to bring it back. In the few times where I did stop Nick because I thought he was too off track and Samantha agreed, I felt bad. I wanted to hear more of what he had to say. One time he clearly didn’t know where he was going, so he was okay with it. But a different time, he seemed genuinely bummed–he knew what he was going to say and now wasn’t getting the chance to say it. But at that point, it felt too late; since we had already paused his argument, even if we wanted to give him a chance to restart, he would have been out of his flow. Ultimately, interrupting the player as they were speaking was a rarely-utilized mechanic because, since it was arbitrary, it felt mean spirited and not fun to use. Even when I or others should have been cut off, we weren’t. This made the competitive element of the game a lot less compelling. I can easily imagine that if people want to “properly” score their opponents and cut people off the moment they seem to stray from the prompt, the game as a whole (the aesthetic) would feel mean spirited. The way we played it, the points really didn’t matter at all and it was totally relaxed. (In part this is due to the fact that the website doesn’t aggregate your points across rounds, and we didn’t keep track ourselves.)

In our game, we want the points to matter, encouraging lighthearted competition but without resulting mean-spirited play. We also don’t want people to be unfairly cut off mid train-of-thought. We solve this by motivating on-topic conversation in a way which doesn’t involve cutting players off. Both sides get equal time to talk no matter what. While it’s possible that people will vote for the winner in a way that is strategic or spiteful, since it doesn’t directly affect the play of the game I don’t think it will yield a mean-spirited aesthetic.