An Introduction to Monikers

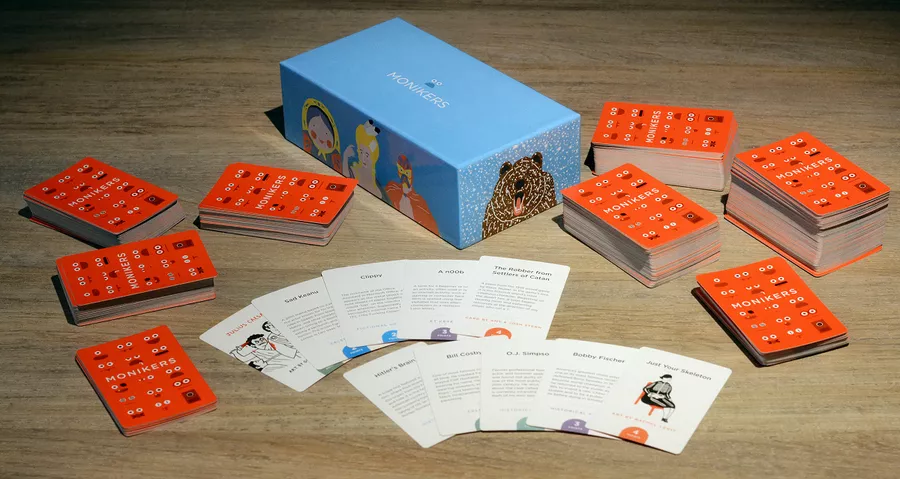

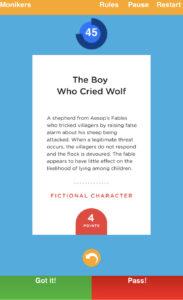

Monikers is a party game for groups of 4-16+ players that takes around 30-60 minutes to complete. It was developed by Alex Hague and Justin Vickers from the CMYK team targeting players age 17+ due to potential vulgar and historical topics. Although Monikers is originally a card game, there are online versions that attempt to recreate the game – one of which I used to play with my group of 4.

Central Argument

Monikers centers around teams using words, sounds, and gestures so their teammates can the names of people on as many cards as possible in 60 second rounds — a guessing game with dynamics consisting of communication constraints, creative thinking, and inside jokes where the magic circle is “blurred”. These create aesthetics like challenge, fellowship, and expression in which our game’s concept also attempts to achieve. I argue that the similarities between Monikers and our game lies in deductive gameplay and restrictions on communication, while their primary differences center around the dynamics used to achieve the aesthetics, such as bluffing in our game, and the amount of resources available per game.

Drawing from Differences and Similarities

Our game’s concepts revolve around a secret that is shared between real friends and, unknowingly, fake friends whose goal is to share it with enemies. Thus, the first major similarity between our game and Monikers is deductive gameplay, in which all roles have information that should be shared or kept from others. In Monikers, words, sounds, gestures are all valid communication techniques under a time constraint of 60 seconds per round. The first round allows all forms of communication, the second round limits clue-givers to just one word and gestures, and the final round limits clue-givers to just charades. When my group played, the dynamics every round as a result of the restrictions. In the first round where we had open communication and were not used to the time pressure, we sat at a table not using any gestures and gave longer descriptions as clues. Faced with restrictions of just one word in the second round, my team moved to the living room where we used our bodies to communicate. The implicit expectation for the amount of cards guessed per team dramatically increased, leading to increased urgency and peer pressure dynamic that escalated in every round. The game’s mechanic choices for these dynamics were smart in that they kept the time limit of 60 seconds per round consistent despite increases in restrictions, accounting for the dynamic of memory utilization spurred from having three rounds per game. Users then use resources such as how many cards are left in the deck to quantify how they can beat the clock, giving way to dynamics such as time optimization.

This feeling of challenge and fellowship was sought throughout our game development process, and with a general theme of increasing difficulty per round, our game also utilized a mix of gestures and statements to convey clues. With the addition of “tells”, fake friends and real friends can communicate with each other to know what the “truth” is, while enemies and fake friends also share a tell in order for fake friends to communicate to the enemies what the secret (that the enemy isn’t supposed to know) is. In this sense, the deductive gameplay centers around balancing a multitude of gestures and being aware of the questions asked for fake friends and enemies to know what the secret was. However, we were unable to reach the urgency that Monikers spurred, given that the goal to win was to reveal one secret rather than multiple. With a 5 minute round instead of 60 second rounds chosen as a result of our disparate win conditions, the dynamic our game produced as a result was bluffing, which happened when players attempted to fill time after they were able to figure out the tell and decipher the truth. This means we reached the aesthetic of expression in a different sense by allowing players to “act”.

The other dynamic Monikers and our game shared in common were strategy development and dynamic learning and adaptation. By keeping the time limit consistently at 60 seconds per round and adding restrictions to communication, the game forces players into a situation where they must adapt to the restrictions while optimizing for the same amount of time. The resources provided by the game for them to still beat the clock are abundant – allowing players to see the amount of cards left in the deck, allowing for repeat cards for both teams until one team correctly guesses the card, giving clue-givers the option to pass on a card or go back, for example. These resources were all used to turn the game from one of independent deduction per team to blurred boundaries of the “magic circle” where people not actively participating in the clue-giving or answering can still benefit from watching. That’s exactly what had happened – in the run of Monikers with my team of 4, since we were all spread out in a living room and watching each pair go, when the time came up for my duo to give and answer clues, we were able to recall the other team’s experiences and guess the cards they couldn’t. When it came down to just the last 4 cards in the deck, the winner of the game ultimately depended on if the team that’s up remembers what the team that went before couldn’t.

Our game’s concept sought to help players develop strategy as well, but in a different manner – we attempted to do so by giving users less resources to start with instead of more, with players only knowing the time, certain player’s rules, and the creator of the secret the only one that knows the full truth. As a result, our discussions were much slower and more thought out, with players developing strategies that don’t take short cuts due to the lack of any time or peer pressure – in this sense, the game turned out to be independent strategy development. In the second and third rounds of Monikers, teams learned that they needed faster explanations per card that can be diminished to just gestures due to the added communication restriction. This inherently created a dynamic of inside jokes, with my team coming up with a clue for honey boo boo as “what rhymes with money moo moo”, or Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow simply being “moo”. When it came to the third round with charades, the inside jokes were simply translated into gestures, such as pretending to lick an object as a clue for “Dr. Henry Heimlich” (pronounced Heim-lick), as seen in the picture below.

Instead of just the team that is currently up and giving and answering clues being a part of the “magic circle”, by the third round, all observers and players were inside of it, watching each other to develop strategy. In our game, the players were not able to develop strategies that branched outside of the “magic circle” and were confined to the predetermined mechanics. Moniker’s dynamics appealed to the expression and challenge aesthetics of the game, yet our team’s attempt relied on dynamics that required thorough strategy development and no short cuts – a trade-off between urgency and strategy realized when comparing the two games.