“How does the game compare and contrast with your team’s concept?”

Game Title: What Do You Meme? (WDYM?)

Target Audience: Mature, since there is adult content in many of their packs. However, some packs, like their ‘Family Edition,’ can be played with parental guidance. This game is meant to be played with friends, family, and strangers who want to experiment socially with their sense of humor.

Creators: Elliot Tebele, Ben Kaplan; published by What Do You Meme, LLC.

Platforms: Card; unofficial online adaptation called ‘We Meme.’

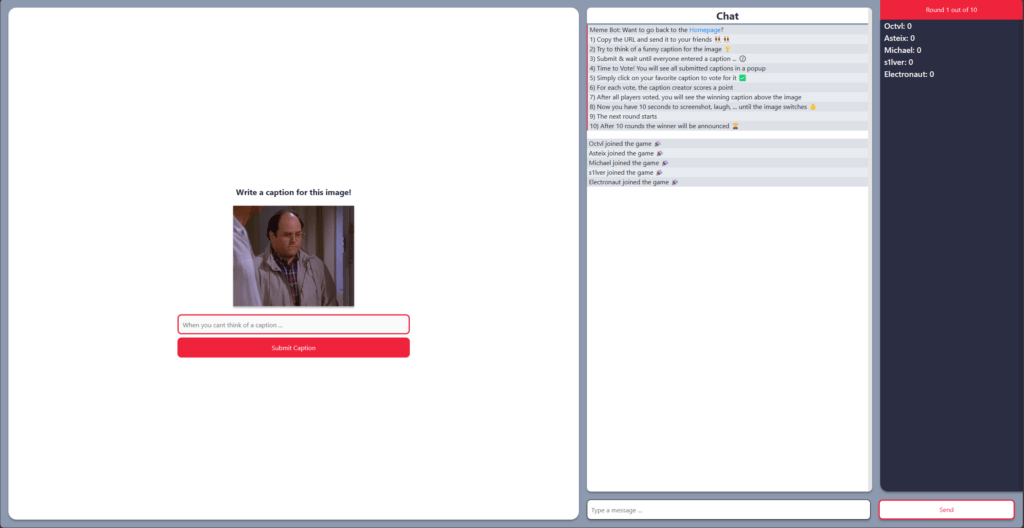

Platform Used: ‘We Meme,’ an unofficial online adaptation of the original card game.

My team has decided to design a card game called ‘Worrywrecker’ which attempts to crowdsource solutions to the group’s current worries– whether close and personal or satirical and fictional. We decided to compare our creation with the existing card game, What Do You Meme?, which is very similar to another game called ‘Cards Against Humanity’. All of these games center around a group of players creatively generating responses to a given prompt with points awarded to the “best” response given according to a selected judge. However, each game is differentiated by its theme: WDYM? uses ‘memes’ while Worrywrecker uses ‘worries’. WDYM? uses pre-made, image-based prompts to ground the game’s current round objective. Worrywrecker, on the other hand, uses player-generated text-based prompts to focus the player responses around for that round. The image prompt in WDYM? allows for a wider range of interpretations than text-based prompts like those found in ‘Cards Against Humanity’ since different aspects of an image prompt can be the specific point of interest when choosing an appropriate response.

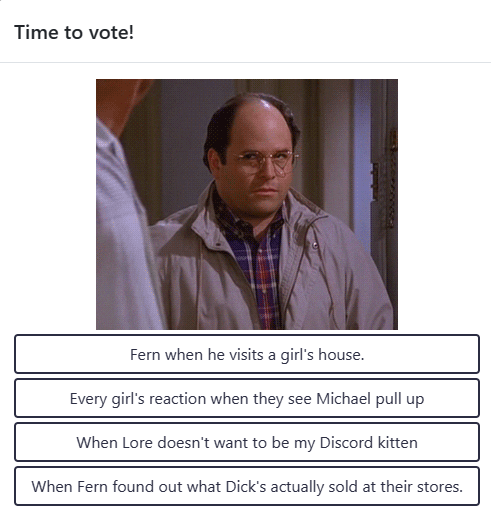

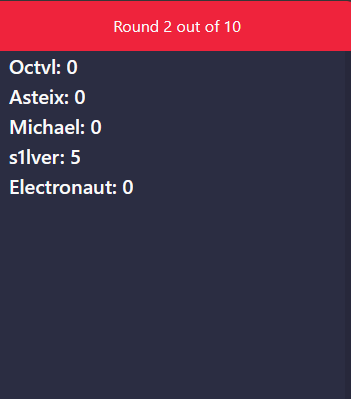

For example, when given a GIF of George Costanza from Seinfeld reacting in a relatable way, some of my friends focused on making inside jokes, others focused on generating hypothetical scenarios where such a reaction would be elicited, and others used sheer absurdity and shock to win over the judges. When reading each response, the author would try to defend their response by elaborating on what aspect of the picture inspired them: facial expressions, background scenery, and the specific show the GIF is from, to name a few. The screenshot below demonstrates one of each of these strategies. The first response was an inside joke about my friend Fern and his recent awkward experience visiting a girl’s home after meeting her at a bar. The fourth response focused on Costanza’s facial expression, claiming it to be the same one a friend would have if they were placed in a fictional scenario. The third response appeals to the “shock” involved in the judge’s reading of the response out loud to the group as opposed to the specific image and how it may connect, relying mainly on the “vibe” of the GIF instead of its content.

When my friends and I played ‘We Meme’, an unofficial online adaptation of the original card game, we were in a group Discord call to help facilitate our conversations instead of using the built-in chat feature. There are two main differences between the online and card versions of the game. First, responses are not pre-written so players are allowed to write custom responses. Secondly, the image prompts were mainly animated GIFs whereas the card version, due to the limitations of its medium, are all static printed images. The ability to have custom responses initially made the game more whimsical to play than pre-written responses since we could make inside jokes that were more contemporary and personal. However, a downside to this approach is that this creative freedom quickly got out of hand. Responses became more exaggerated as shocking responses commonly would receive more votes than those directly related to the image. This implicitly became the ‘meta’ winning strategy since the judges would share their dark, adult sense of humor. The image became less and less important in determining the winner of a round. This is an important trend to be wary of when allowing our players to write custom prompts and deciding whether players’ responses should be pre-written or open-ended.

Worrywrecker is similar to WDYM? in that there is one new judge with every new prompt. This change in judgment should help share the level of executive power each player has in shaping the course of the game, making every player feel like an important part of the group. However, this dynamic breaks down when most of the judges have a similar sense of humor or interpretations of the game’s open-ended goal since points are given at the sole, subjective discretion of the judge. Nevertheless, as long as its players are having fun (which is subjective), the game is accomplishing its goal. The lack of a concrete winning condition makes both games feel like an open opportunity to take measured risks with their fellow players and discuss tangential topics at length when they arise.