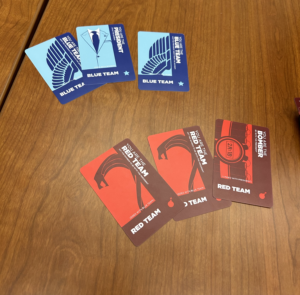

The game I played for this week’s critical analysis is Two Rooms and a Boom, created by Alan Gerding and Sean McCoy. The game targets players ages 8+ and is a social deduction, card-based game played by assigning role cards to different players. Based on the card they’ve been assigned, players are divided randomly into the red team (one of whom is the bomber) and the blue team (one of whom is the president) and separated into different rooms, with the option to trade people between the rooms every round. The red team wins if the bomber ends up in the same room as the president, and vice versa for the blue team.

However, while Two Rooms and a Boom is a social deduction game, with certain mechanics similar to our own, it does not make explicit—nor emphasize—the collective storytelling aspect in the way our own game, Ghostwriters does.

To begin, Two Rooms and our current version of Ghostwriters do share a few key mechanics, largely the idea that there exist two assigned teams, as well as certain hidden identities that both sides are trying to deduce. For Two Rooms, these are the red and blue teams, as well as the bomber and president. For Ghostwriters, players are assigned a subject, and go around in a circle to tell a story one sentence, trying to incorporate their subject. Two of the players (the ghostwriters) will be assigned the same subject—the goal of each player is to then guess which two are the ghostwriters at the end of the story. In this way, our game also implicitly divides the players into two teams—the ghostwriters vs. normal authors—if less explicitly than Two Rooms does. There is also the notion of uncertainty of who is on which team that is common between the two games. Players in Two Rooms can refuse to reveal their card; players in Ghostwriters aren’t allowed to, as the main goal is to guess this division.

However, within this idea of hidden identity, there emerges a difference between the two games. In Two Rooms, each player knows their own identity. In our game, this isn’t true—you do not know if your assigned subject is one of the duplicated one. In this way, Ghostwriters adds an additional layer of challenge-type fun that doesn’t translate into Two Rooms. Not only are you trying to deduce the identity of your fellow players (author or ghostwriter), but also your own. This also creates a new consideration for players when deciding how much information to mete out.

Additionally, while it’s arguable that Two Rooms does involve some sort of storytelling (i.e. telling a story, truthful or not, about which role you’ve been assigned), it’s not truly a focus of the game. Though players can really step into their roles and talk in a way that fits the clever aesthetic, premise, or narrative of Two Rooms, in actual gameplay, this turns out to not be a priority. When I played, many of the negotiations were rather straightforward: I’ll show you my card if you show me yours, which team are you claiming to be on, are you the president, and so on. There aren’t a lot of options for what you can do—either you reveal your identity to some subset of the people in your room, or you don’t. It is a lot of fun involved in trying to get other people to reveal their cards to you, guess what their reactions indicate, and choose a “hostage” to swap rooms, but oftentimes, players choose not to reveal anything for strategic purposes. In this way, even while you are an active player in Two Rooms, it’s highly likely you aren’t really contributing anything to developing game or “narrative” that has been set for you.

In Ghostwriters, this is the opposite. Negotiations of information and identity happen solely and explicitly through players’ contributions to the story. Once again, this adds an additional layer of challenge-type fun: how are you going to formulate your sentence that it reveals enough about your theme to identify your fellow ghostwriter (and help them identify you) while not so obvious that all of the authors catch on as well. This mechanic—the creative decision involved in where you want to take the story next—also invokes a sense of self-expression that isn’t present in Two Rooms.

Moreover, the mechanic that all of the players are creating a story that they can look back on at the end of the game also differentiates the game in formal elements. While both games do center on team vs. team competition, Ghostwriters has this additional element of cooperative play, where all players, regardless of team, are coming together to tell a story. In this sense, it can also be said that Ghostwriters invokes discovery as well—players are together mapping out “uncharted territory” by seeing just how far the story can go.

In sum, Two Rooms is a really fun and clever game, and there’s a ton that we can take away from it. The styling of the game in particular felt very slick, and while we didn’t play the “advanced mode”, some of the additional role cards that are used there looked super interesting, definitely give us ideas for how we can extend our own game. However, for players looking for more freedom in response, cooperative play, and challenge in social deduction, Ghostwriters differentiates itself from Two Rooms as the better fit.