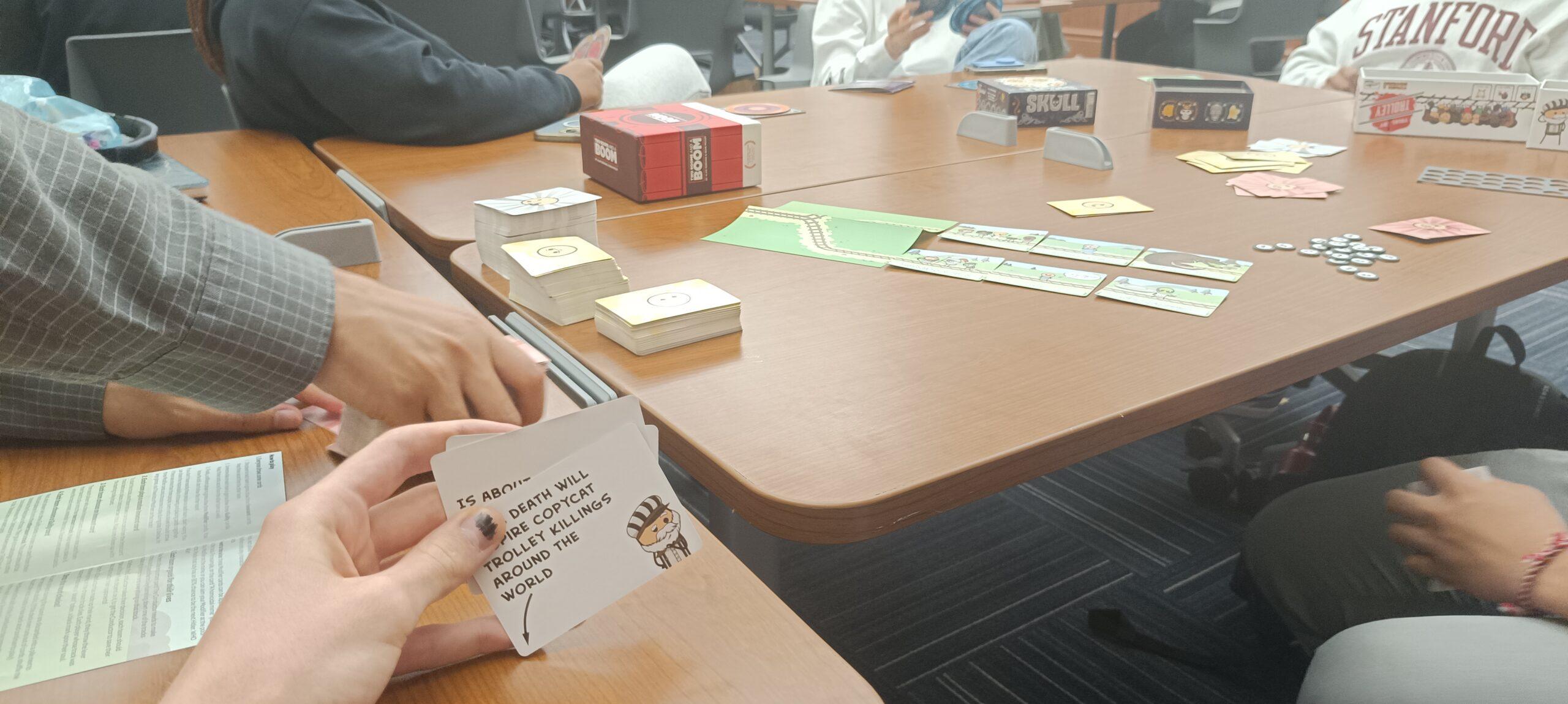

For my critical play, I played Trial by Trolley, a debate based card game designed by Scott Houser for 14+ audiences. It’s simple to pick up, but poorly balanced, and similarly to our concept, its replayability falls off sharply once the players have familiarized themselves with the cards.

Much like Ghostwriters, the game concept my team is working on, Trial by Trolley depends on a deck to provide novelty. Once players have played enough to see the whole deck, it no longer meets that goal. However, much of Trial by Trolley’s humor comes from the cards themselves, which are inherently somewhat humorous and have amusing cartoons on them, whereas our concept uses a simple deck of nouns that could be interchanged with similar decks from other games. This means that our game’s replayability is less reliant on the cards themselves, which is good for us. However, Trial by Trolley also alleviates the replayability issue by ensuring that cards are played together, meaning that every combination creates a new entertaining scenario. As there are far more combinations than cards, this extends the game’s replayability; an advantage that our game concept does not share. Furthermore, Trial by Trolley’s engagement with moral concepts makes it excellent for getting to know people on a deeper level than mere icebreakers, as well as making it more fun to play with people you already do know well. All you learn about your friends from playing Ghostwriters is who is a bad storyteller. This isn’t necessarily a flaw with our game, not every game needs to provide deep insight into the moral philosophy of the people around you, but it provides insight into one direction that the game might benefit from growing.

Like many similar games, Trial by Trolley primarily emphasizes the aesthetic of fellowship, with undertones of expression and challenge. These types of fun become apparent as players socialize with each other, practice their rhetoric, explore their own moral systems, and compete against one another. Players construct an underlying scenario for their arguments by playing cards, creating a strategic dynamic wherein players must set the stage for the debate in advance. This dynamic contributes to the latter two aesthetics by giving players the opportunity to choose what sort of position they want to express, and challenging them to select one that will allow them to defeat their opponent. This dynamic is constructed by the structure of the rules, which require players to select the cards from a hand of possibilities. That mechanic leads to much of the strategic challenge of the game. The mechanic of debate, which is directly outlined in the rules, also contributes to all three kinds of fun identified here by creating a space for expressive social competition. These details make the game quite entertaining on first playthrough, but it’s only on subsequent ones that the problems with the game design become clear. Strategy falls by the wayside once you become familiar with which cards tend to be most effective, and once you know the main arguments for the cards the expression aspect gets minimized as well. What’s left is a learned pattern: a game that isn’t fun anymore.

For our game, we hope to reduce the impact of this issue by including a large quantity of cards, ensuring that the cards don’t limit gameplay too much around themselves, and sourcing the novelty in our game from the players rather than just the cards themselves.