Introduction

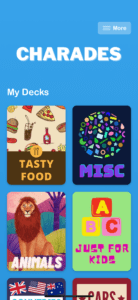

Charades, the classic word guessing game, originated in 16-century France. While the original creator is unclear, the app version I played with my friends is developed by Dmytro Cheversa. There are various versions available across iOS, Android, and web. This game is intended for everyone, whether it be family, friends, or strangers. In this app version, it’s obvious that the developer wants to ensure the game is accessible to everyone, since there are multiple decks, including ones dedicated to kids (image shown below).

The mechanics of Charades is straightforward. Separate the group into 2 teams. In each team, someone will be the guesser while others be the actors. The chosen guesser of each team will select a deck, place the phone in front of their forehead, and the other teammates will act out the word for them to guess without talking. Since there are only 3 of us playing the game, we modified the game so that each person takes turns to be the guesser while the other 2 act. This modification results in an interesting combination of multiplayer co-op and multilateral competition. That is, the 2 actors cooperate and try their best to act to help the guesser obtain the score, yet we’re all competing against each other at the same time. I assume this dynamic would change if there’s a player who’s primary goal is to outcompete everyone else. For generosity purposes, I would analyze Charades in a the traditional team versus team player structure.

Central Argument

Charades and our game are both round-based guessing game where each team compete against one another to maximize the score they obtain. While both games’ aesthetics arise in fellowship, challenge, and expression, the key differentiators of two games stems from our game’s core mechanics and extension of fellowship.

In our game, players need to draw cards of a scenario, roles, and limitations. For instance, the team draws a scenario card “A and B are exploring a haunted mansion”, role cards “nerd, pizza delivery guy” and limitation cards “speak in high-pitch voice, laugh randomly.” Then, the actors will act out the scenario with their designated role under the limitations within 1 minute. The team obtains a point if they guess correctly within the 1-min time bound. If not, the other team can steal their point by guessing after the 1-min time bound.

Where does the fun come in?

Both games are zero-sum game that are structured as team versus team. Since obtaining a point relies heavily on actors’ acting skills and guesser’s guessing ability, challenge become one of the core aesthetics of both games. Specifically, in Charades, the challenge for the actors is a word that’s difficult to perform. In our game, we add additional layer to the challenge by using a specific scenario, designated roles, and some limitations that might be hard to incorporate.

Fellowship is fostered among each team through collaboration and communication. In Charades, my friend and I collaborated to act out doghouse, where I acted as a dog and she acted as a house. The time pressure forces us to quickly brainstorm multiple acting solutions and act beyond our normal behavior (i.e. I barked), fostering a sense of connections when we let the guesser guess the word. In our game, fellowship emerge in a similar fashion, where teammates need to communicate transparently on how each role will play out. However, our game extends the element of fellowship by adding constraints to the role and some improvisational element. The unpredictable combination of roles and limitations force players to collaborate creatively to brainstorm methods to incorporate the limitations into the game, while improvisation requires each player to adapt to another player’s crazy idea. Through communication and acting, aesthetics of expression arise when one acts out how they perceive a word in Charades or a scenario/role in our game, resulting in some form of performing arts.

Improvements

While Charades adds fun over my weekend, there are several things that can be improved. 1) It’s easy to simply point to an item for the guesser to guess what the word is and 2) close friends can use inside jokes to gain more points. As an example, when I got the word “wheel,” my friends pointed to a wheel and allowed me to guess easily. For the second case, when my friends and I are acting out the word “vegetables,” my friend acted by showing that this is something she doesn’t like eating but what I love eating. While this amplifies fellowship through friends’ inside jokes, in the case where close friends are playing with strangers, strangers might felt excluded as they don’t understand the inside jokes. We can eliminate both cases with the new mechanics in our game. By combining scenarios, roles, and limitations, players are forced to act under those constraints and not have too much freedom in simply pointing at an object or referring to inside jokes that match directly to the scenario.

Conclusion

Overall, I really enjoyed playing Charades with my friends and have felt a sense of fellowship fostered afterwards. I’ve discovered another part of them that I’ve never seen outside this magic circle. With our game, though, I believe we can foster the sense of fellowship even stronger with a different core mechanics.