About

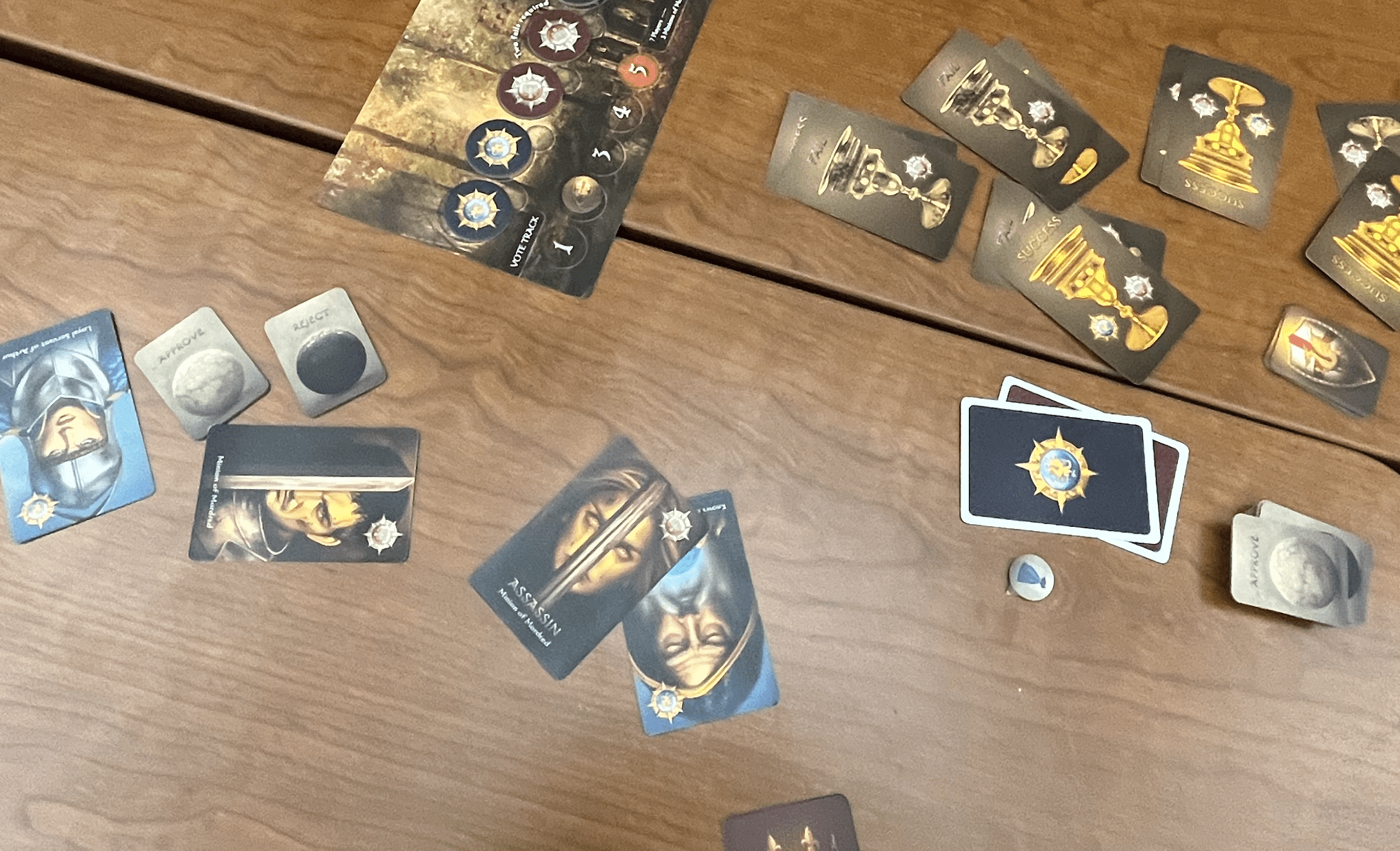

- Game: Avalon, a King Arthur themed-variant of the social deception game Resistance

- Creator: Don Eskridge

- Audience: The game is intended for 5-10 players, aged 13+, and caters to a fairly wide audience in terms of reach with the rules of the game being relatively easy to pick up compared to other social deception board games. Often played at parties and among large friend and family groups, it appeals to any player seeking out any type of fun ranging from fantasy to challenge to fellowship.

- Platform: The standard version is a board game, but during the pandemic, several web versions of the game were created by third-party developers based on the physical board game. My team played in-person using the physical version which was critical for a more engaging gameplay experience. In-person play made for more interactive and successful discussion regarding the outcomes of quests, forming alliances, convincing others of your loyalty, etc. Observation of gameplay was also far easier; associating people with physical space in a room made it easier to remember which teams were chosen, who voted acceptance or rejection, pick up on nonverbal cues, etc.

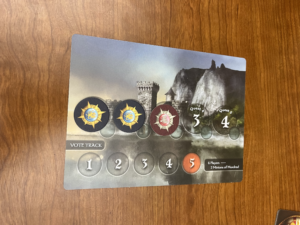

Basic premise: Avalon is a social deception game where two teams, the Loyal Servants of Arthur and the Minions of Mordred, compete with hidden identities. Only the Evil team and Merlin know the evil players. The game involves quests led by chosen players, voted on by all. Success or failure of these quests determines the game’s outcome: Good needs three successful quests to win; Evil needs three failures, Merlin’s assassination, or five consecutive quest rejections. Additional roles like Mordred and Percival introduce more strategic knowledge sharing.

How does the game emphasize social deduction through its mechanics?

Central Argument: Avalon emphasizes social deduction by creating an environment where partially hidden information is key, team alliances are uncertain, and player interactions are the primary means of uncovering the truth. More specifically, these elements of social deduction are sequentially established in the mechanics of the team formation stage, the quest formation and voting stages, and in guessing of who Merlin is for attempted assassination.

Mechanics for each game stage and how they contribute to social deduction:

- Team formation/role assignments: the path to social deduction starts with the formation of the Good and Evil teams. With special role exceptions, only Evil members know who each other are (similar to Mafia). Merlin also knows who the Evil team is. Unlike standard Mafia, for larger groups of players (7+), additional roles also allow for selective knowledge e.g. Mordred (whose identity is unknown to Merlin) and Percival (good-aligned, knows Merlin’s identity). I appreciated the designer’s choice to include these roles; in Mafia, the detective only learns the roles of individuals one round at a time, leading to slower game play depending on the size of the teams. Our team played a couple rounds without Mordred or Percival and one round with. As a two-time recipient of the Merlin role, I found it challenging to balance risking revealing too much knowledge versus selecting quest members that would not result in a favorable outcome for evil. This constant dilemma is a clever decision by the game designer. The risk of assasination at the end forces Merlin to not overtly only choose all good people for their quests or to blatantly reject quests that have certain individuals. In our final game, the final round was down to 2 Good wins vs 2 Bad wins. As Merlin, I decided to take the risk of selecting an all good team to avoid an automatic win by Evil. My certainty in choosing the team, however, did end up with my assassination. The inclusion of Percival (with knowledge of Merlin’s identity) can help to alleviate some of the suspicion on Merlin, as they can act in a way that “accidentally” reveals their selective knowledge.

- Room for improvement: 1) Merlin’s challenge of influencing the game without revealing too much could perhaps be alleviated by introducing a mechanic that allows Merlin to give indirect hints without revealing his role. 2) the final guess can sometimes feel anticlimactic, especially if the Good team has played well throughout the game only to lose based on a successful Merlin identification; perhaps there could be an opportunity for more misdirection in which another player can temporarily take on a Merlin-like role.

- Room for improvement: 1) Merlin’s challenge of influencing the game without revealing too much could perhaps be alleviated by introducing a mechanic that allows Merlin to give indirect hints without revealing his role. 2) the final guess can sometimes feel anticlimactic, especially if the Good team has played well throughout the game only to lose based on a successful Merlin identification; perhaps there could be an opportunity for more misdirection in which another player can temporarily take on a Merlin-like role.

- Quest formation and voting: The primary mode of gameplay is through quests: each round, a leader(rotates) selects other players to go on a quest, after which everyone can vote to accept or reject the quest. If a quest goes through, quest members individually decide whether the quest should be successful or a failure. Good wins upon 3 successful quests (if Merlin is not assassinated at the end) and Evil wins upon 3 failed quests or if 5 quests are rejected in a row. The quest formation is trickiest if you are good aligned, especially at the start of the game, as standard players have no insight into who is on their side. When voting, good-aligned players have to be certain that every single person on the quest team can be trusted, since a single Evil player on a team can be enough for failure. In our gameplay, good-aligned players tended to err on the side of caution, often rejecting quest teams multiple times in a row if they suspect an Evil person was included. I appreciated the game designer’s inclusion of the 5 consecutive rejection rule, as excessive caution can slow the game down and sometimes lead to frustration. Analyzing who selected what teams and rejected when/how often is the primary metric for determining team alliances. In our game, putting down too many rejection votes in a row, especially early on in the game where little info is known, was interpreted as the voter being a knowledge-bearing role (Merlin or Evil). I was quite suspicious of Amy at one point for putting 4 rejections in a row right from the start of the game, hinting that she was potentially evil. We also strongly relied on listening to one another’s reasons for choosing quest teams, especially when people deviated strongly from choosing the same people from a prior successful quest vs adding in new people. We noticed that several times, someone would claim they were switching up the team for “data” , which usually indicated they were Evil aligned.

- Room for improvement: For two of our games, the 3 quest requirement to initiate a Good win occurred very early on since the Evil players were too cautious about revealing themselves, leading to an anticlimactic conclusion; perhaps, new mechanics could be added to protect the identity of Evil players during early quests or encourage more incentive for making risky decisions like a successful quest unlocking additional powers.

- “Who is Merlin?”: if the good team wins 3 quests, the game doesn’t end until the Evil team tries to assasinate Merlin. This stage still offers the Good team a chance to help protect Merlin’s identity through deception, or serves as a time for the Evil team to reflect on the prior gameplay and critically discuss. This is where memory of previous voting patterns and quest assignments is critical to making a successful deduction. I found it amusing that one player in particular (Lucien) had an iPad and was the only one diligently taking notes, so people tended to take his observations as ground truth. When one player attempted to lie about their rejection of two quests in a row, Lucien was able to counter their claim. An example of failed deception that occurred in our game at this stage: prior to the reveal of specific Evil roles (only the general identities of the evil-aligned people had been announced), a teammate who was Good asked who Mordred was (which I as Merlin easily knew based on my knowledge of the other Evil identities during the game). This significantly reduced the chance that this player was Merlin, since the question was asked quite sincerely. I did appreciate how this stage was the only real “elimination” feature of the game, unlike Mafia where players die after each round. All players remain active in Avalon, contributing to discussions and decisions until the game concludes.

- Room for improvement: the heavy dependence on memory of voting and quest assignments can disadvantage players who lack a strong memory for details; perhaps a notepad and pencil can be provided for each player to keep track of each round, similar to how Clue operates.

Merlin assassinated after Percival’s slip up

Merlin assassinated after Percival’s slip up