Introduction

“Secret Hitler” is a compelling multilateral competition, social deduction board game, created by Breaking Games. It’s inspired by the historical context of Hitler’s Germany and the era of the Fascist party. Although this game was originally a board game, a fan has made an online version which we played via www.secret-hitler.com. Designed for an audience with a grasp of complex rules and historical nuances, “Secret Hitler” targets young adults to adults, offering a rich experience of social deduction and strategic gameplay that demands engagement and critical thinking. This game is a staple for social gatherings, where strategy, deceit, and historical insight play pivotal roles. Although the players don’t exactly need to know what a fascist or liberal is to understand the game, it does help in better appreciating this game, and this game adds more fun when the players understand the concepts.

Central Argument

“Secret Hitler” excels in its portrayal of social deduction through meticulously designed mechanics, setting it apart from other games in its genre, such as “Among Us”. For instance, in “Among Us”, when players receive “Crewmate” as their role, they are instantly saddened because they didn’t get “Imposter” instead. So all they can do is sit back and do their tasks, while also viewing who passes them and coming across the occasional misfire from an Imposter. It is much more relaxed and they don’t have to critically think at all points in the game. In addition, they only have one specific goal they are assigned, which is completing all given tasks. However, “Secret Hitler” ensures constant engagement through its unique blend of strategy, probability, and role secrecy.

Analysis and Comparative Study

In this argument, Among Us Imposters have the same role as Secret Hitler Fascists, and Among Us Crewmates have the same role as Secret Hitler Liberals. There are similarities in both games such as all fascists and all imposters know who are each other. However, it differs in the gameplay of both. For instance, when you are an imposter, you can “fake” doing tasks; however, you can’t actually perform them. But in “Secret Hitler”, even if you are a liberal, you may be forced into an unfavorable decision under the guise of either “probability that 3 fascist cards were given to the president” or by a fascist president that provides only fascist card options, and now you must place down a liberal card. This mechanic not only deepens the gameplay but also mirrors real-world scenarios of misinformation and trust.

This is the same case for the flipped roles, where you can place down a fascist card as a liberal, and then now you must try to escape any blame by saying it was your only option available. Therefore, you have a lot more pressure and have to escape hard evidence of performing another team’s role. This creates more excitement due to these mechanics, setting it apart from other games in the genre by allowing every player to participate actively and critically at every stage. This game creates a constant and dynamic environment of suspicion, alliance, and betrayal. Comparatively, games like “Among Us” focus more on task completion with sporadic moments of deduction, lacking the continuous strategic depth “Secret Hitler” offers.

However, Secret Hiter’s reliance on historical and political understanding may limit its accessibility to a broader audience because most people who are either not knowledgeable about these events such as kids, or those who are completely agnostic to these historic events would be turned off when hearing the name of the game and how it relates to Hitler. An improvement could involve incorporating educational elements that provide historical context without detracting from the gameplay. This addition could enhance understanding and appreciation for the game’s thematic depth. It would also help kids who have yet to learn about this event in history class to learn about the important events in this game. One way to do so is to add a card that can change things up and provide historical context. Similar to how Monopoly has “Chance Cards”, Secret Hitler could invoke a similar thing, providing these cards that players pick up when hitting certain milestones so that they can obtain some sort of power while also giving the narrative of Hitler’s regime.

Integration of Learning and Formal Elements

Drawing on the MDA framework, “Secret Hitler” skillfully integrates its formal elements to craft a game that is both intellectually engaging and emotionally compelling. The mechanics of secret roles and policy enactment lead to dynamics of suspicion and alliance formation, which in turn evoke the aesthetic experiences of fellowship and competition. The reasoning for these two in particular can be drawn from the games we played as a group. Fellowship is the most obvious: we were all communicating together and trying to playfully outwit the other players if given the fascist role. Whether it’s anti-fellowship with players not trusting one another, or fellowship between liberals working together or even liberals working with unknown fascists, this game creates a lot of talking points and ways of communicating even for new players playing their first ever game of “Secret Hitler”. As for competition, it is very clearly competition from the competitive atmosphere. We are all trying to win, and no one knows each other’s roles other than the fascists who know each other. That means only so many people can trust one another, and it creates a sense of competition as everyone is trying to win against one another.

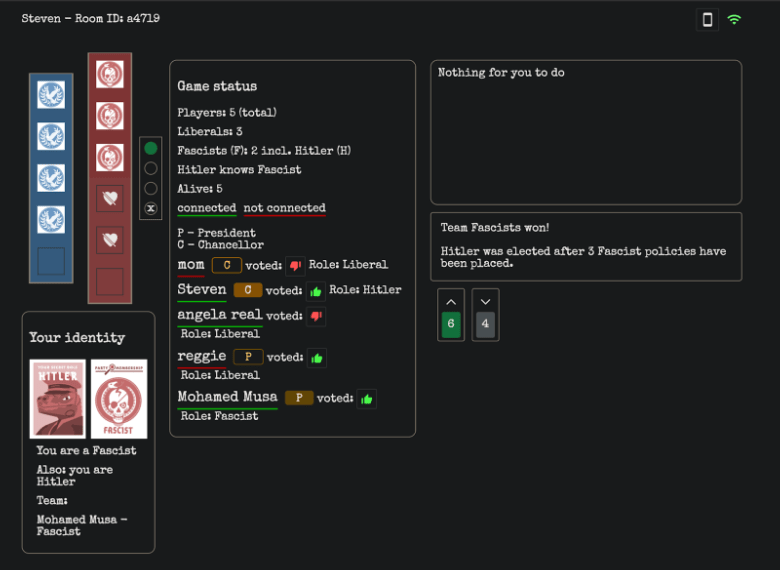

A specific example of both of these aesthetics in our games that made it fun was when I bluffed my friend Regina. We would always fight with “fellowship”. For instance, I would always vote no for Regina to become the Chancellor in all the previous games. And then when I was a Fascist and Regina was just a Liberal in a separate game, I was able to make her trust me by giving her two options, a fascist card, and a liberal card, and then once she chose liberal, I was like “oh I trust you now Regina” and that caused Regina to trust me too. Then because of that, she was the last deciding vote in our game (you can see the screenshot) for whether I was elected chancellor, and the vote ended up as 3 yes, 2 no, and because of that, I was chancellor, but we had 3 cards already on the fascist board so then the fascists won because I was Hitler and won the game! That was super fun and Regina felt so betrayed. But through the formal elements objective of outwit, I was able to get Regina to trust me and help me win. And because I was able to outwit, that was a huge point for me having a lot of fun. As for the other players in the game who were Liberals (Regina included), they had a sense of “discovery”. Some of them trusted me and realized they were betrayed, while others didn’t trust me and realized it was correct after I won and blamed those who did trust me for voting “yes”.

Conclusion

“Secret Hitler” stands out as a masterpiece of social deduction, leveraging its historical theme and complex mechanics to foster an environment of constant engagement and strategic depth. It challenges players to think critically, communicate effectively, and navigate between trusting and deceiving one another. Through its innovative design and effective use of the MDA framework, “Secret Hitler” not only entertains but also educates, making it a valuable addition to the genre and a testament to the power of well-crafted game design.