I played Spent (playspent.org) which is a game that tries to educate the player about the difficulties faced by those living in poverty in the United States and the types of financial tradeoffs they might have to make.

Mechanics:

- 30 choices for each day of the month

- Weekly income via a job

- Money counter

- Persistent options for emergency money

- Persistent ‘problems’ such as medical bills to be paid

Dynamics:

Each day, the player needs to consider which option to select, weighing to preserve their funds while also spending wisely to prevent even worse problems from occurring and attempting to do good and live by their values (e.g. providing an good childhood for their kid).

Aesthetics:

The types of fun present in this game were fantasy (roleplaying situations that the play will most likely not experience), narrative (understanding the life of your character), challenge (trying to make it through the month without running out of money), and expression (applying one’s personal value system in making choices in the game).

Outcomes:

- Increased empathy for those with financial struggles

- Better understanding of the financial tradeoffs made by those struggling with poverty

- Information about resources people may take advantage of and and ways to help (being encouraged to donate).

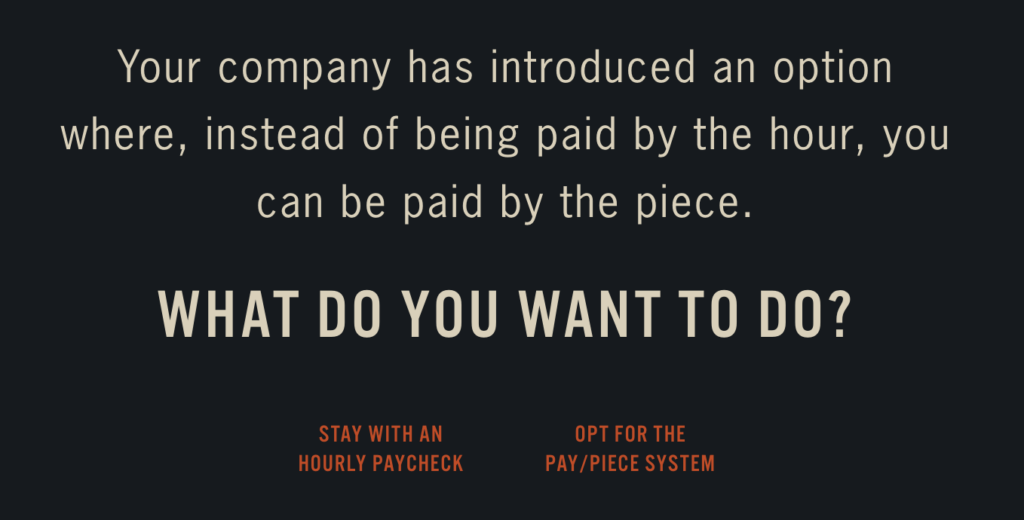

One think I liked about spent is that it broke the rules of standard interactive RPG/IF games for rhetorical effect. Standardly in a game, I expect to understand the tradeoffs behind the choices I’m being presented. Common mechanics are one option might be riskier but have higher reward, or maybe one option has a random chance to help or hurt, but regardless this is usually made apparent to the player, either explicitly or through context, so the player can make an choice and feel as if they are making a strategic decision and exercising autonomy in an informed way. However in Spent, this almost never happened. I was presented with choices such as this one:

In this case, I had no idea how each option might affect my budget. (I took hourly and got my income cut by 50% because of it). From the perspective of player autonomy, this may have been an unpleasant dynamic, but I really appreciated the procedural rhetoric of showing the player the confusing tradeoffs people are presented in real life by making them guess their way through many very bad options. Real people in most of this situations would have equally little if not less knowledge of how to progress, and that symmetry made the message of the game more powerful. To recap in terms of the MDAO framework, the game used a mechanic of presenting choices without information, creating a mechanic of making uninformed choices, leading to an aesthetic of confusion and an outcome of increased sympathy for those unable to make informed choices about finances in their real lives due to the lack of transparency in real systems.

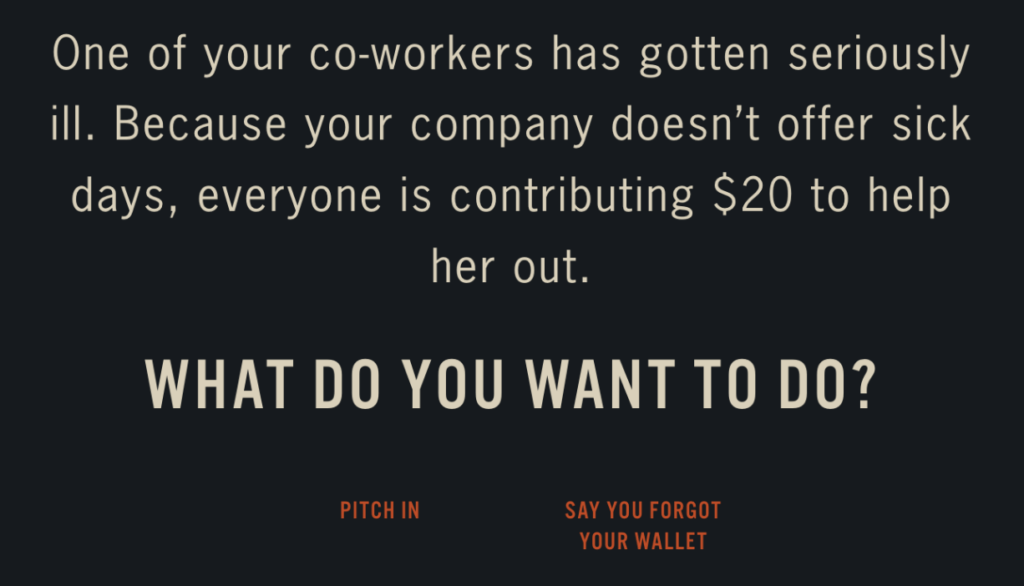

Another common type of choice given by the game were those like this:

Options like this one play have no clear consequences for not giving money, but play on concepts of social shame and responsibility to give the choice weight. Many games apply this dynamic of having the player make moral choices to supplement the limited mechanics of the system, but it seemed especially applicable in Spent where the entire game has a specific moral emphasis