Due to an unfortunately timed COVID case and a couple of personal issues, I was unable to complete a lot of the individual assignments in CS 247G when I took it in Spring 2023. I was fortunate enough to work with a fantastic team, and we produced Zoo Frenzy and A Flood in the Desert as our projects – these are just my individual assignments. In order to avoid flooding the feed, I’m uploading all of my material here. Have fun reading 🙂

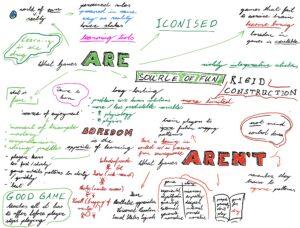

Sketchnote: What Games Are and Aren’t

Critical Play: Your First Critical Play

I played Among Us from Innersloth on my iPad with a group of friends over Zoom. Among Us is an espionage game aimed at a broad audience of all ages, mainly with a focus on interpersonal intrigue and social interaction. Our game included seven players, two of whom were designated as ‘Impostors’ at the start of each round. The impostors were tasked with assassinating other crewmembers without being detected, while those crewmembers were capable of calling group meetings to identify impostors. This led to a great deal of negotiation, bluffing and accusation among our group, the antagonistic nature of which is relatively unique for such a co-op focused game – since each player doesn’t know who to trust, efforts to convince the team of an impostor’s identity quickly grew heated and chaotic. This was a very fun atmosphere to play in, maintained by frequent plot twists when an ejected crewmate was revealed to not be an impostor, or when a particularly convincing argument that one wasn’t the impostor turned out to be a complete lie. Compared to other games in the genre I found it dynamic and extremely enjoyable with friends, though the lack of systemic gameplay variety gave me the feeling that playing for hours at a time could grow quite boring. If I were asked to make any changes, I would maybe introduce some modes with increased randomness in events and roles to keep the gameplay feeling fresh, especially for groups who don’t know each other as well.

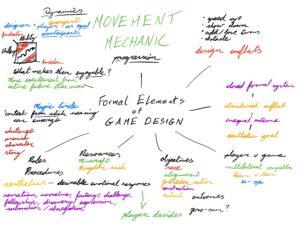

Mind Map: Formal Elements of Game Design

Blog Response: Visual Design of Games

Skim & Watch: MDA & 8 Kinds of Fun

One game in which the mechanics create a dynamic that make a certain kind of fun for me is Apex Legends, specifically the movement mechanics that allow players and their teammates to navigate the map through an expressive dynamic. Apex’s movement mechanics priotize speed and fluidity above most other factors, all with a focus on maintaining momentum as effectively as possible. Where many other FPS games alter their physics to prioritise realism, or exaggerate the player’s abilities to achieve a very specific, unrealistic aesthetic, Apex maintains realism in most cases but breaks from this in its sprinting, movement-while-shooting and sliding. This leads to a system that reads as more realistic than its peers (such as Titanfall 2 from the same studio), but deviates just enough to give the game a unique expressive aesthetic focusing on a kinetic sense of motion. This lends a frantic, experimental energy to the game’s battle royale gameplay. Personally, this has led to incredibly memorable situations like sliding off a blimp , aiming down sights and landing a sniper shot on an enemy before I hit the ground. Alongside the other aesthetics achieved by Apex Legends (most notably fellowship), the game’s movement mechanics allow me to express myself in a way rarely found in a first-person shooter.

Blog Response: What do Prototypes Prototype?

- How can we ensure that the player becomes quickly invested in the story?

- This is important for ensuring that the player feels motivated to investigate the game’s core mystery & compelled to keep playing the game.

- We would need experience prototypes testing the design & writing of our game to query players as to their feelings regarding the game’s story.

- How can we inform the user about the world’s history without overdoing exposition?

- I believe our early prototypes will not generate a great deal of investment from users, since we haven’t refined our writing and design very well so far. Use testing will be essential in determining we make the right decisions early, so that we can reach a point of investment as quickly as possible.

- How can we refine gameplay that makes the user feel skilful & accomplished within the format of a point-and-click adventure?

- Potentially exploring minigames related to activities at various points of the story could help us to decide exactly where we can inject skill-based games to assist with pacing.

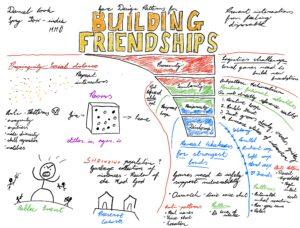

Sketchnote: Game Design Patterns for Building Friendships

Critical Play: Bluffing, Judging and Getting Vulnerable

For this assignment, I played a digital variant of Cards Against Humanity called Evil Apples. It’s made my Evil Studios Ltd, and we played on Android and iOS (my version was iOS). This allowed me to compete with friends from home over the internet, while otherwise keeping the same gameplay structure as Cards Against Humanity. We played in a group of 6 players, with 1 designated as a judge reviewing the cards selected by the other 5. A prompt card was brought up each round, and players could choose insert cards to place into the prompt’s blank spaces. This causes player resources (word cards) to be withheld or used based on a user’s judging of their potential for the current prompt card vs. any potential prompts that may come in future.

In terms of ‘kinds of fun’, this primarily prompted fellowship – despite the competitive mechanics, the game mostly focuses on group judgement of jokes & humorous responses. The writing of the prompt and word cards served as foundations for this, though in my opinion the writing wasn’t as good as in standard Cards Against Humanity. It felt like the funniest cards mostly stood out to shock value due to lewdness, which produces some especially funny moment but got old once it felt like the majority of good jokes shared this common element.

To improve the game, I would definitely invest more in the writing in addition to improving networking features – we called over Zoom to communicate during the game, due to a lack of voice of video chat. I felt like an in-app video chat feature could have added to the experience by showing players’ reactions and potentially incorporating funny filters as cards, etc. We didn’t need to get particularly vulnerable, aside from the occasional discovery that a joke we thought was hilarious wasn’t particularly good at all.

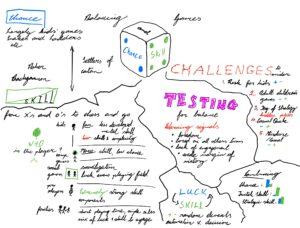

Critical Play: Games of Chance

I played online poker with a couple of my dormmates who play each week. I definitely felt out of my depth, since most others in the room were much more experienced than I was. I also didn’t have the money (or want to spend it) on staking, so this make the whole thing quite low-stakes. That being said, I had a good time but distinctly felt my lack of control – without much experience, it felt like there weren’t many areas in which I could exercise skill to improve my performance in poker’s online format.

Sketchnote: Balancing Games: Chance and Skill

Critical Play: Walking Sim

I played Journey for this Critical Play, and was profoundly affected by the game despite its relatively slow pace and simple mechanics. I found that the walking mechanics and tiny visual or gameplay quirks (the hindered movement on sand, the main character stumbling against the wind, etc.) made me particularly invested in the protagonist’s progress on the journey, despite the lack of exposition regarding purpose or motivation. The game’s design and music also greatly contributed to this – the aesthetic thrill of discovering a beautiful new landscape or piece of music motivated me just as much as any gameplay could. I also ran into another traveller at one point, communicating through a very simple singing function and travelling together for a few minutes. This made me feel deeply connected to them despite our lack of deep communication.

Finally, my favourite particular of the game’s walking mechanics are the effect they have on the game’s final act – once we start flying towards the end of the journey, it feels freeing and exhilarating largely because of the dramatic change of pace from the slower walking of the rest of the game. Overall it was a beautiful experience, and the walking as a medium only helped to enhance this experience, giving time to consider the artistic achievement of the game while also providing a sense of release at the end.

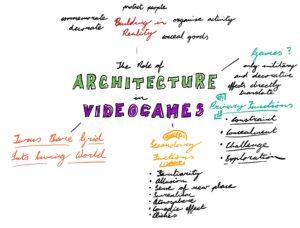

Sketchnote: Designer’s Notebook: The Role of Architecture in Videogames

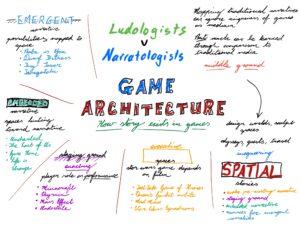

Sketchnote: Game Architecture: How Story Works in Games

Critical Play: Mysteries

For this critical play, I chose to play Episode 1 of Life is Strange, which I found engaging but not enlightening in the way I had for the previous two games on Critical Play. I liked the degree to which the narrative is woven into the mystery through the game’s cold open in the supernatural disaster before flashing back to Max’s present day in her photography class. This was an intriguing opening, establishing the mystery of Max’s powers while keeping their origins secret. I could surmise that the opening was a real glimpse at the future through her powers rather than a dream, but enough of the details were obfuscated that I still wasn’t certain at all how that disaster could happen or what consequences it could have for the game’s characters. These time travel powers also interact with the game’s decision-making mechanics in an interesting manner. Where similar choice-based games (like Telltale’s the Walking Dead) can leave you unable to explore every avenue of the story without multiple playthroughs, Life Is Strange’s status as a mystery game means that missing out on details due to direct choice could damage our ability to uncover enough details to keep up with the mystery or feel a sense of agency within it. Given this, the choice of time travel as a power works extremely well with the game’s mechanics, maintaining a sense of mystery effectively without incurring too much of an opportunity cost as a result of the player’s decisions.

However, there were a couple of issues that I had with the game itself. The dialogue between the teenagers never really felt accurate to me – this could be due to the near-decade of passed time since then, but a lot of the students’ dialogue felt extremely expository and laden with strangely used slang that it took me out of the game. Some of the environmental storytelling also felt a bit heavy-handed, particularly the ‘missing person’ posters for Rachel Amber plastered all over the game’s environment left me feeling overly ‘directed’ towards certain discoveries, breaking the game’s immersion. A similar issue was present in the graffiti around Chloe’s room (such as CAN’T SLEEP above her bed) felt similarly heavy-handed. I will likely play further in the game, but I encountered enough issues in the first episode that I don’t feel compelled to finish in quite the same way I did for Journey and Fez, despite the interesting and accomplished way Life Is Strange’s mechanics supported its mystery.

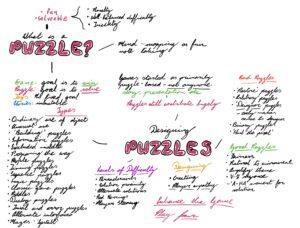

Sketchnote: Puzzles in Games, Puzzles as Games

Critical Play: Puzzles

I played Fez for this Critical Play, and absolutely loved it. The 2D-to-3D transitioning mechanic forced me to consider each level and its permutations in ways I often couldn’t even fully see, forcing me to deeply consider each level’s specific design in a way that prompted a ‘V-8 response’ extremely frequently. The depth of design to each area also intrigued me beyond the game’s standard ending – I found myself revisiting previous levels to uncover new ‘cubes’, and loved doing so due to the game’s fantastic visual and auditory design. The concept as a whole was one I found incredibly fresh, and was almost shocked that it hadn’t been accomplished before – the 2D-3D perspective shift not only provides an original narrative impetus for the protagonist’s ‘hero’s journey’, but also forced me to deeply consider the intricacies of each level in a way I never had before in a game. There are still plenty of ‘cubes’ I haven’t found, and I look forward to working through them every now and then for the next while.

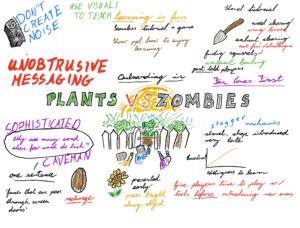

Sketchnote: Onboarding in Plants vs Zombies

Critical Play: Is This Game Balanced?

For this critical play, I chose to focus on one of the first video games I ever played – a fan-made 2D Sonic game called Ultimate Flash Sonic created by menace ch. My cousins introduced me to this game years ago, and it’s still hosted on Game Sloth at https://www.gamesloth.com/games/sonic/. This kick-started my interest in videogames at around 8 years old, but I hadn’t played it in at least a decade, so I figured it would be a good case to revisit.

I have a pretty good memory of the difficulty I experienced when first playing the game as a child, so I can somewhat compare my two experiences of the game’s challenge on either side of the skill level bell curve in order to identify how well-balanced the game actually was. Unfortunately, my memory of the game was that it wasn’t very well-balanced – I would frequently die to factors that felt largely outside of my control, and this could be incredibly frustrating. However the core gameplay loop was engaging and fast-paced enough that this rarely stopped me from playing, even though I rarely made it through the game’s two zones (each with two levels and one boss) without exhausting my three lives.

Revisiting the game years later, my initial perception of the game’s balance unfortunately holds up, though I’m now much better able to identify the source of difficulty that makes the game feel unbalanced. Collision detection is kind of a mess – the player character can normally kill enemies while in ‘spin dash’ form, but in apparently random cases the player will instead take damage while contacting an enemy even in this form. Additionally, some enemies (specifically the penguins in Zone 2) seem to have strangely large hitboxes, meaning they can kill the player without apparently touching them. This is especially problematic given the lack of an invincibility period once the player is hit. In the couple of other Sonic platformers I have played, Sonic loses all his rings when hit but gains a second or two of invulnerability in order to land safely and give the player an opportunity to recover some rings without dying. Here, that isn’t the case – Sonic bounces uncontrollably backwards when hit, often landing on another hazard without any opportunity for the player to avoid it, killing him instantly.

There are also issues within the level design itself. Rings are often placed at locations that the player doesn’t touch while running straight, forcing them to double back and halt the momentum of the game in order to collect them – the exact opposite of the speed-first approach that made Sonic games popular in the first place. Additionally, the narrow field of view means that for rotating traversal aids – swinging handle-like things that the player can grab, then let go of to launch in a chose direction – the player often can’t see any landing spots on the screen while holding the handle. This turns the jump into a blind leap of faith in which the wrong choice leads to death. Similarly, the two Dr. Robotnik boss fights are oddly balanced. Since Robotnik himself doesn’t move, the player can sit at the back of the screen and wait for an opening indefinitely, leading to a lack of tension. Also, the hitboxes on the final boss fight feel egregious – the player can hit ‘explosion’ JPGs long after they impact, which feels physically unnatural. And the reward system is fundamentally unbalanced – rings reset every level and I can never seem to find 100 in a single level, even without getting hit. This makes new lives practically unattainable, which is a particular issue given the many ways in which the player can die without making a mistake. The reward system also doesn’t make any sense – there are no power-ups, but ‘cheats’ can be unlocked by completing the game with specific characters. These cheats range from useless (such as a ‘Tails’ companion that follows you around but doesn’t do anything) to almost game-breakingly bad (like a ‘behind’ cheat that obscures the player behind foliage and other environmental elements, making them invisible for large chunks of levels).

All of that being said, the game still plays quite smoothly and looks & sounds almost like the real deal. For a fan-made game, the degree to which the developers refined the feeling of jumping and running is genuinely impressive. The mechanics feel like a real Sonic game, meaning that when not confronted by enemies or other opportunities for imbalance to affect the experience, it’s actually quite fun to run through the game’s environments as fast as possible. But aside from the poorly balanced enemies, the game is actually quite easy at this point – I ended up beating it multiple times without ever running out of lives. This indicates that beneath the large number of singular issues of imbalance, the game’s difficulty itself is poorly judged, at least on this side of the bell curve. I can’t say that was an issue I realised when I was younger, but I definitely remember the frustration caused by hitbox and field-of-view problems. So on the whole, despite my fond memories and the couple of impressive gameplay particulars it pulls of, I can’t claim that Ultimate Flash Sonic comes anywhere close to being a balanced experience. I think I still love it anyway.

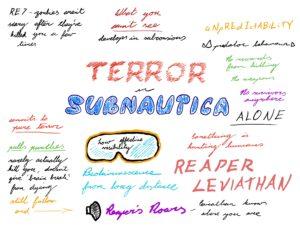

Sketchnote: Terror in Subnautica

EXTRA CREDIT Critical Play: Theme Only Games

For this critical play, I chose ZeptoLab’s Cut The Rope and Rovio’s Angry Birds, two of the earliest successful physics-based mobile games, but ones that differ slightly in their theme. Both are bright, colourful and centre around expressive animal protagonists (a colourful cast of destructive birds, and a cute but undefined creature called ‘Om Nom’). Both games also share many mechanical broad strokes – both are focused on destroying parts of a pre-set environment in order to achieve a goal. These principles of physics drive the gameplay systems of both, but the difference in thematic context between the two games significantly alters my interpretation of each.

The primary objective of Cut the Rope is to feed Om Nom by cutting ropes to guide a piece of candy towards his mouth. The aesthetics of the game evoke a kind of child-like, nostalgic sense of innocence and curiosity, with the structures of strings and ropes kind of resembling a digital playground. The general vibe of the game is very subtle, exploratory and non-competitive, encouraging players to try different routes with the ultimate goal of making a cute creature happy.

On the other hand, Angry Birds is slightly more action-oriented and adversarial. There is slightly (very, very slightly) more narrative complexity here, with the game opening with a series of panels depicting a group of goofy green pigs stealing the birds’ eggs, prompting them to get angry and go after the pigs to retrieve their eggs. Where Cut the Rope used softer colours and lines with slower music, Angry Birds uses bold colours, bombastic music and exaggerated impact sound effects to enforce a more destructive form of gameplay, with the player launching different birds in order to destroy pigs’ forts. A three-star scoring system for each level also encourages players to accomplish their goal using as few birds as possible, placing a strong emphasis on efficiency.

This duality presents Cut the Rope as a game more focused on a more relaxed, playful form of entertainment in comparison to Angry Birds’ more competitive, destructive vibe. Despite the visual and mechanical similarities between the games, they serve as an interesting case study in the different forms of engagement achievable by games as a medium, where even a minor delineation in theme can lead to two divergent but equally engaging experiences.

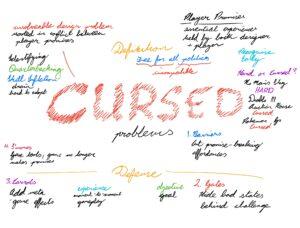

OPTIONAL Sketchnote: Cursed Problems

Final Class Reflection

Despite the strange start & continuation of my engagement with it, I really enjoyed my experience with this class and was inspired by the new ways in which the staff approached both teaching (in the distributed group setup with guest lecturers and project work) and learning (in our individual assignments for Critical Plays and Sketchnotes). It simultaneously encouraged me to explore the creative side of my thought process and the myriad ways in which a problem could be approached while also granting a great experience of working on a team on a large, medium-term project incorporating numerous practicalities like user testing. Before this class, my approach to note-taking and general gathering of information for classes was very linear – despite being a fairly creative person, I feel like academic systems and perceived efficiency drew me towards a very standardised form of note-taking that I knew didn’t leverage all of my creative energy or broad memory in the way it could, but for habitual reasons it was very hard to break out of. Sketchnoting, in particular, was a really great way of exploring outside the boundaries of that space I had worked in for quite a long time, and while my technique definitely isn’t where I’d like it to be, it’s absolutely something I will look to work on in future.

Similarly, I went into the class with a fairly rigid experience of game design. It’s something that I’ve been keenly passionate about for a very long time – I released my first game when I was twelve, and have worked on multiple projects since then – but each of those has been intensely personal projects. Partially for convenience – when learning to code, I found it easier to practice and experiment in more private contexts in which I wouldn’t be concerned with others’ judgement – but if I’m honest with myself, a lot of my drive towards working on these projects alone came from a reluctance to open myself up to criticism and to expose my ideas in contexts where they might be questioned or amended. While I’ve worked on teams effectively in the past, game design always felt personal enough to make me guarded about it, rather than eager to share & test my concepts in a way that exposed them to the input of others. Despite being forced to miss the first while due to a COVID case, I was able to integrate into my team very quickly and our in-class exercises facilitated a very relaxed, collaborative atmosphere that I felt really encouraged me to be more expressive in my suggestions and less precious about my own ideas, which allowed them to be more easily incorporated and improved by the team as a whole. This wasn’t exactly a switch that suddenly made me entirely comfortable, rather I felt that this openness was something that was repeatedly and actively incentivised by the tasks that we were given to work on. So while now I still definitely feel the same protectiveness over my creative work, it’s been effectively amended by an extremely positive experience of having done things very differently & seen the benefits that can be achieved through it. This is truly rare for a college class, especially in a CS discipline that can feel increasingly pressurised and academic, so I really appreciated the way in which CS 247 actively encouraged my openness and creativity.

If anything, that’s what I will look to take forward into my games or other work in future. The act of developing a game itself is one I’m lucky enough to have experience with, but I hope to engage in it much more honestly and effectively by trying to back away from the more insular approach I have taken in the past. I’m at a point of technical confidence where interpersonal judgement doesn’t concern me too much, and a point of creative openness that I feel allows for much better collaboration than I could have achieved before, and I look forward to seeing what else that allows me to express and make with the aid of others.