Game Designers: Marielle Burt, Alyssa Li, Lucy Lu, Ada Zhou

Overview

Get Schooled! is a competitive, card-drafting game for four to five players. It’s recommended for players aged 10+ and has a play time of approximately 60 minutes.

In Get Schooled!, you are running a high school with a particular educational philosophy. You’ve gotten to know some 6th graders in your district and have learned about their strengths and needs. You have three years to improve your school before they will choose which high school to attend.

Each year, you will divide up your funding in order to hire teachers, train them to teach unique courses, and run special projects – all the while trying to meet national policies. The quality of your school will be determined by:

- The total number of cards you play

- The number of courses taught with your educational philosophy

- How many students decide to attend your school

Learning Goals

We designed Get Schooled! to be played by educators, students interested in education, or anyone who likes games with challenge, narrative, and expression.

Players learn about several aspects of our education system:

- Different ideologies of how curriculum should be designed in school systems

- There are different roles for the players to choose from that correspond to different educational philosophies. We also included a summary of the philosophies and special courses tailored for each.

- The challenge that our education system faces when balancing individual student needs and creating a comprehensive curriculum that serves everyone

- Throughout the game the players need to balance two goals: Recruiting students and meeting their specific needs or creating a school that best follows their own educational philosophy. Both goals provide points but come with different risks.

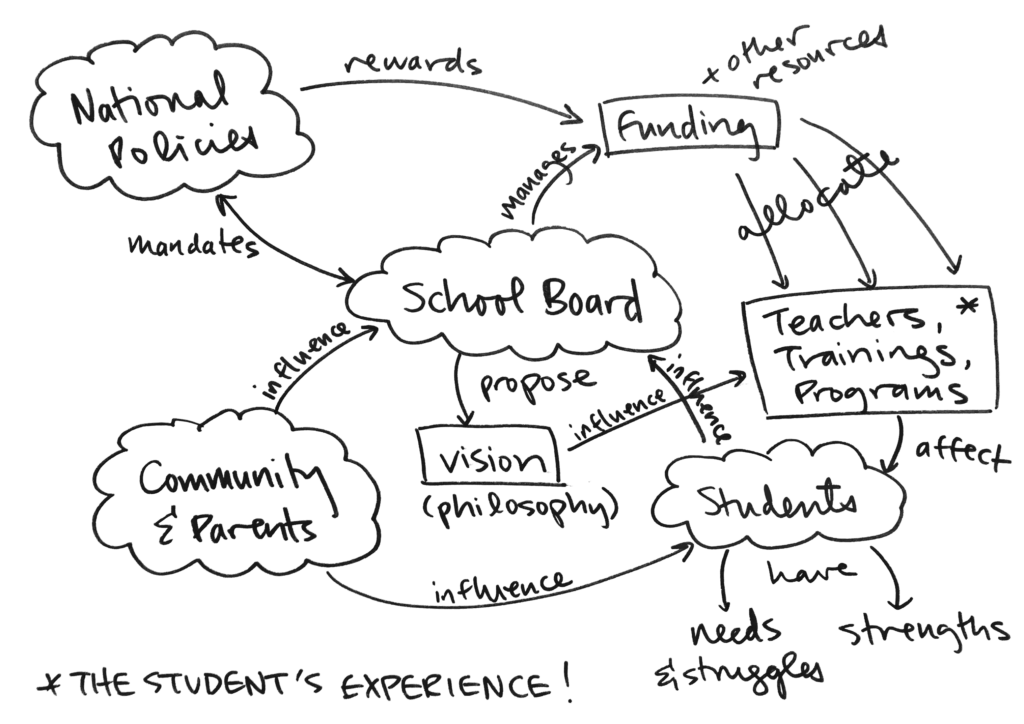

- National and student level influences that affect how schools are ran

- We included national incentives that mimic how federal departments incentivize local school boards with funding, but the schools’ ultimately need to meet the needs of their particular students.

Rules

See full rulebook here and print cards from Figma here.

Concept Map

Formal elements

Loops and Arcs

Most of the gameplay happens in three loops (called Year 1, Year 2, and Year 3). Within each loop, players draw and play cards to create new courses. Together, these three loops form a narrative arc. Each year, players receive more advanced cards and can build upon their previous cards to make more specialized and complex courses.

Game economy

The main economy in this game is a one direction conversion of

Funding tokens-> cards (teachers and trainings) -> classes -> special projects

Both classes and special projects are converted to points at the end of the game. There are several ways these resources influence each other.

- Players obtain cards as turns pass by, and they are encouraged to convert these to classes to satisfy national incentives and obtain funding tokens.

- Different player roles have special ability to obtain (or prevent others from obtaining) cards and tokens throughout the game.

Game Balancing

See the balancing master sheet here.

Deck Balancing:

We treat all cards the same and compute the overall statistics of the deck to ensure that no player has strong advantages (by having more cards that are beneficial to them). This is important since all players are incentivized to build a curriculum that aligns with their philosophy, and since we want to encourage discussion about pros and cons of educational philosophy, we do not want to have cases where one philosophy is overwhelmingly stronger than the others.

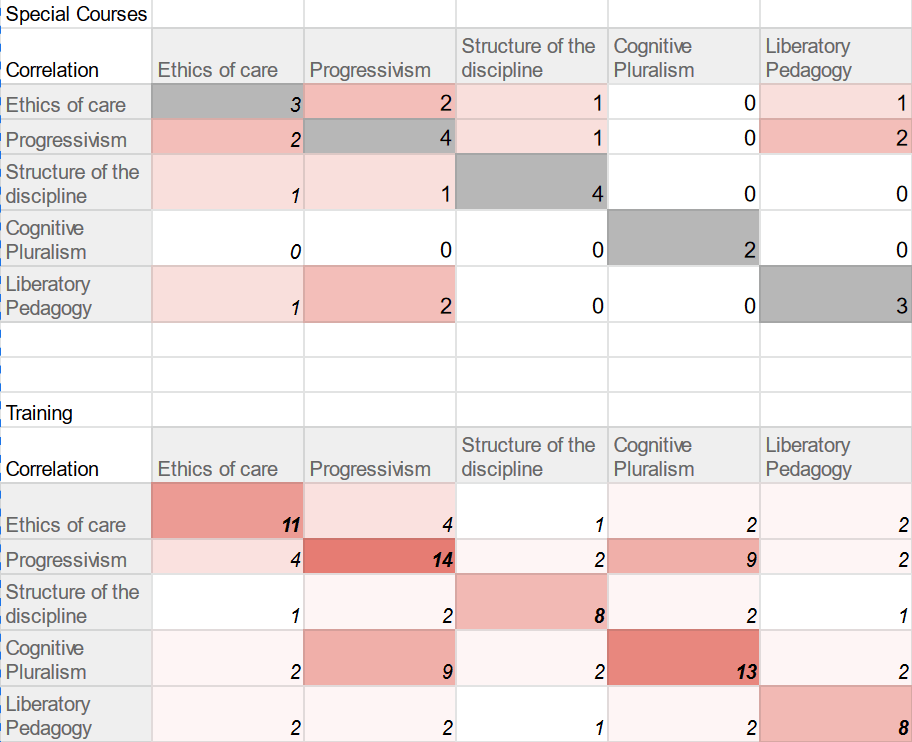

Since one card can provide bonuses for multiple philosophers, we also want to identify correlations between these bonuses, since these cards are going to attract more attention and are relatively harder for any one player to get, due to the competition. For example: this Morality and Civics card is endorsed by 3 different philosophers, so there will be 3 players trying to keep this card for themselves.

Therefore we created a correlation graph for all the philosophies (separated for special courses and trainings, since they provide different point values).

Since Progressivism and Cognitive Pluralism have a lot of cards in common, we increased the total number of cards that have their ideology on them, so that there are enough resources for both players. Notice that we did not try to aim for a perfectly even distribution since that does not truly reflect the overlaps between these philosophies: some of them do align more with the others.

Supply and Demand of Cards:

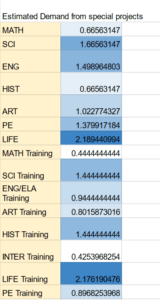

A secondary objective in the balancing sheet is to figure out if there are severely overpowered cards among the special projects. Due to the random drawing process and players taking turns picking cards, we do not worry too much about balancing all cards perfectly, but we want players not to be too frustrated when they try to find the cards they need only to realize that there are none of them left. We computed the estimated demand for each type of teacher and training (by subject) based on the requirements of the special projects. Notice that since teachers can be trained in multiple subjects, if we need one PE class, we require either 1 PE teacher or 1 PE general training, which is why the demand of either card is set to 0.5.

Finally, We tallied the total demand and supply to make sure there is no severe imbalance.

Notice there is higher demand for LifeEd teachers and training, but this is addressed by Noddings (one of our roles) having extra LifeEd cards to begin with, so there is higher total supply for this subject. We also included some lower demanded subjects in the special courses for each role (math and history), so the final demand would be higher. During the final playtest, we did not observe a high imbalance in demand and supply of any particular subject.

Testing and Iterations

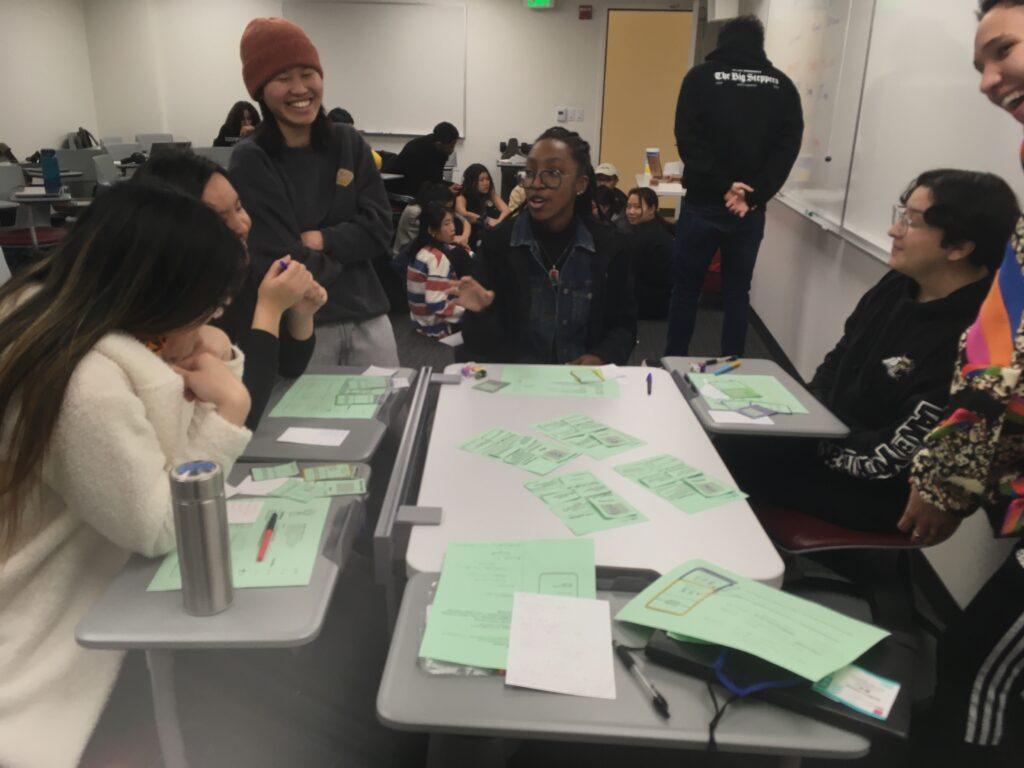

Playtest 1 – February 21

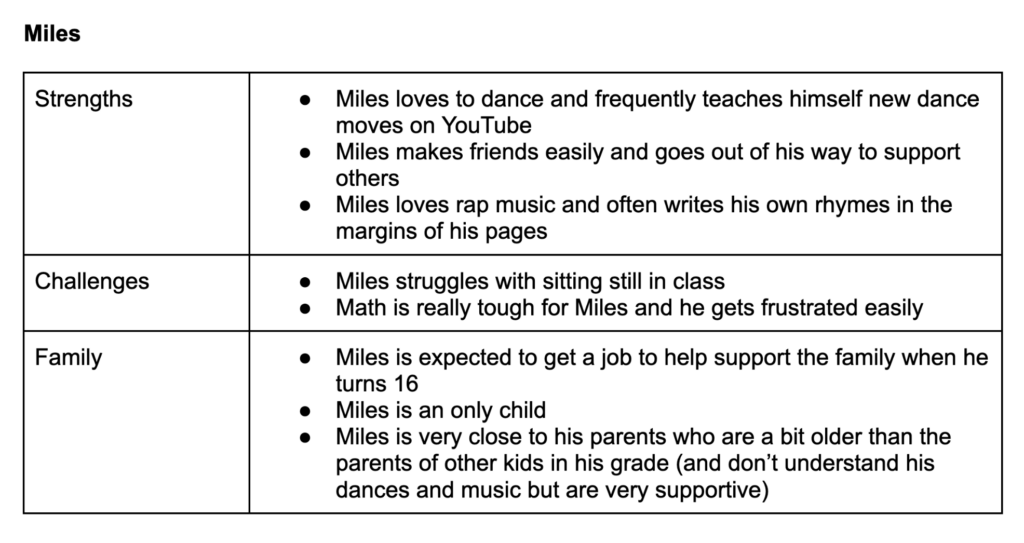

This first prototype was a collaborative storytelling game. Players act as school board members who are deciding how to allocate resources in their district. They each represent a child with specific needs (see example student card below) and advocate for them. Each round, players draw cards and have to decide which Staff, Facilities, and Curriculum cards to use their actions on.

Players

- Amy

- Kyle

- Michael

- Shana

Key Observations

- People immediately liked the story telling aspect of this game and were attached to students

- “He’s just a little firecracker and I love him so much”

- There was a lot of laughter and playful debate

- The way that players were meant to collaborate was murky

Key Changes Made Afterwards

- Made student descriptions shorter, and gave them randomized characteristics

- Added strategy into the game: National Policy that can help you gain funding, cards that can fulfill multiple criteria, a limit on the total number of cards you can play.

Playtest 2 – February 23

Players

- Alejandro

- Alahji

- Charlotte

- Ivan

Key Observations

- Players were competing with one another to try to meet the needs of their particular student – this defeated our overall learning goal that all students needs should be important

- As the players had no specified roles, it also seemed that this version of the game leant itself to quarterbacking

Key Changes Made Afterwards

- Make the game competitive instead of collaborative

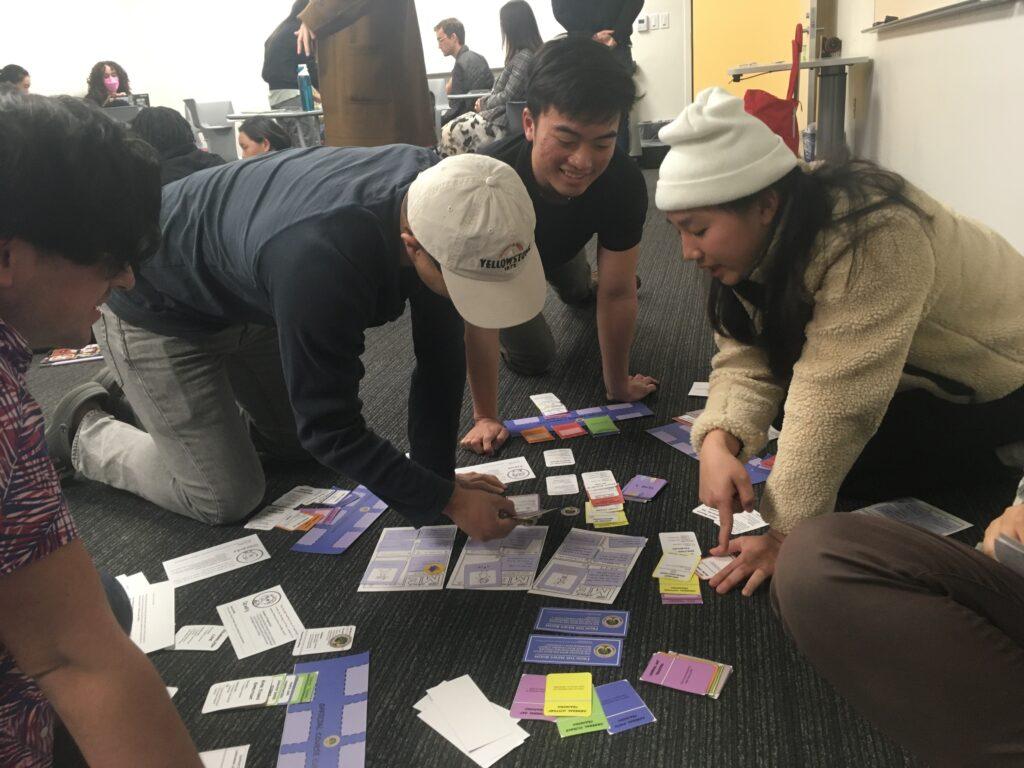

Playtest 3 – February 28

Players

- Annie

- Miranda

- Shana

- Shimea

Key Observations

- Used betting style to determine how many of each card to play. This was confusing, players didn’t like having to decide how to allocate their resources before drawing cards.

- Takes really long for all of the players to talk about each student (since it’s 4 school’s stories per student)

Key Changes Made Afterwards

- Use card-drafting instead of betting. This is more like real life: when one school doesn’t hire a teacher, they look for employment at another school

- Add 30 second limit on storytelling

Playtest 4 – March 1

Players

- Gilbert

- Marielle

- Alyssa

- Lucy

Key Observations

- Basic mechanics work. Now there’s room for more interesting strategy and tough decisions.

- The rounds start to feel repetitive, need more of a narrative arc.

Key Changes Made Afterwards

- Give philosophers abilities that you can use throughout the game

- Make national incentives force players into competition each round

- Unlock new cards in each round.

- Round 1 – general training

- Round 2 – special training

- Round 3 – special projects

Playtest 5 – March 2

Players

- Charlotte

- Ember

- Miranda

- Yuchen

Key Observations

- It’s not fun to make general courses – need to have special training in the first round.

- This group seemed more focused on their individual goals than the needs of the students.

- The game is coming together! Some fun quotes:

- “But do you count your push-ups in mandarin at your school?”

- “This game is super immersive, I like thinking about all the different ways to vision a school”

- “I learned a lot about these different philosophies”

- “I’m taking my school in a unique direction, watch out y’all”

Key Changes Made Afterwards

- Have players draw teachers in setup, so they can make cool courses in Round 1 of play.

- Make the rulebook more clear, so players can learn how to play on their own.

- Emphasize the importance of meeting student needs even more in the rulebook. Make students worth more points.

Playtest 6 on March 4

Players

- Lucy

- 2 friends not from Stanford

Key Observations

- Players did not want to read through the long rulebook. Need to make cheat sheets.

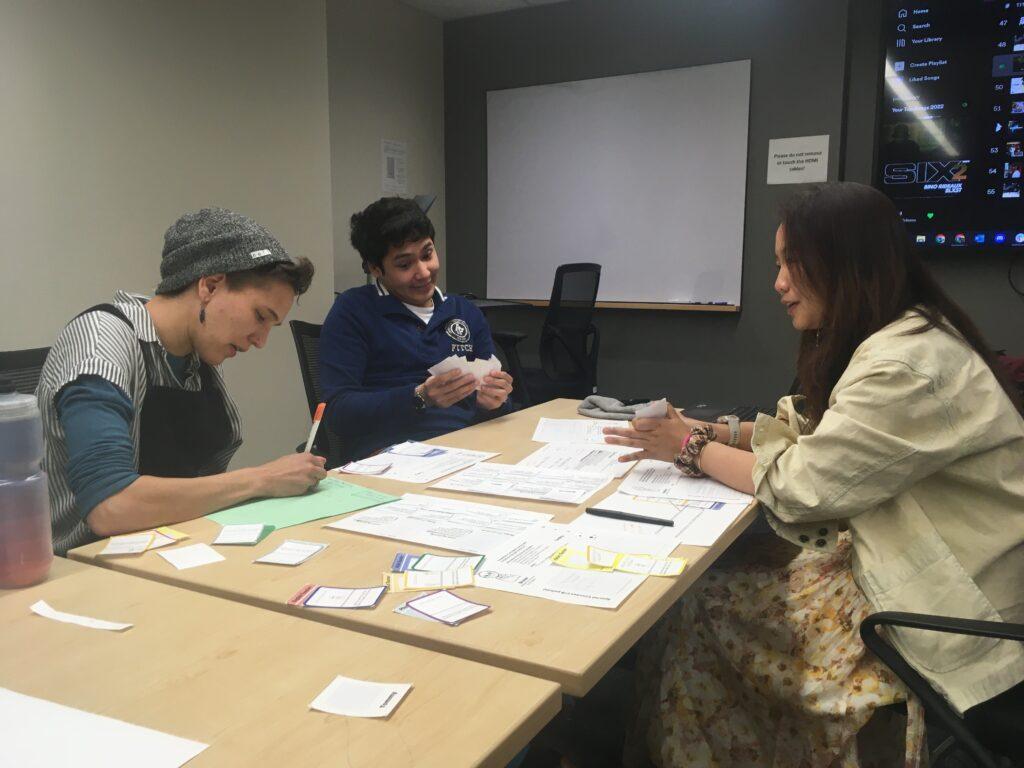

Playtest 7 (Internal) on March 5

Players

- Ada

- Alyssa

- Lucy

Key Observations

- Funding mechanic was too complicated

- Some of us wanted to hold onto cards for future rounds instead of having to commit them to a particular teacher.

Key Changes

- Changed funding into a token that you can spend anytime in order to draw a card of your choice (from any deck that has been drawn from before)

- Make a special board for “confirmed” courses. You can place cards directly on the table and move them around until you “submit/confirm” the stack.

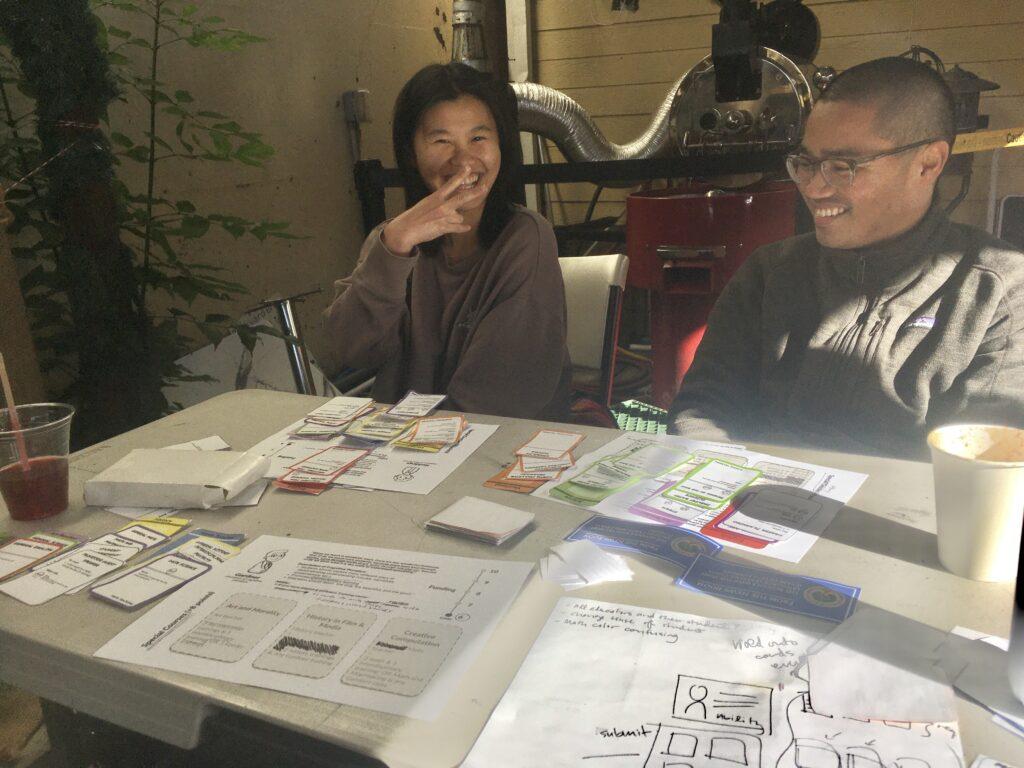

Playtest 8 on March 5

Players

- Ada

- Alyssa

- Lawrence (Stanford PhD Student)

Key Observations

- Funding tokens are a fun mechanic – more people should have the opportunity to use them.

- Liked the pass around mechanic, but the cards near the end are junk.

- Mostly played stacks of one color – there’s not enough general trainings/there’s an opportunity cost to playing them instead of matching colors

Key Changes

- Give every player 1 Funding at the start of the game.

- Let players discard 2 cards at any time in order to choose a general training of their choice. This mimics real life because it takes time for people to get familiar with a new field.

- Add trainings with two colors, since general trainings are relatively scarce. This is also more like real life because certain specialized topics fall between the basic subject categories. (Example: Playwriting could be taught by someone with a background in English or Art.)

Final Playtest 9 on March 7

Players

- Amy

- Ivan

- Kyle

- Michael

Key Observations

- There’s a hump to get over to learn to play the game – and then people start having fun.

- The storytelling is still the best part, so we should reincorporate it in between each round!

- We could simplify the complexity, since National Incentives and the Philosopher Courses take focus away from student needs and make the game harder to learn.

Next Steps

In our final playtest, we discovered some important ways to improve the game. These included some smaller usability fixes as well as more meaningful alterations and ideas to explore further:

- Improve cheat sheet

- Create score card

- Add more storytelling throughout the game

- Add images for all of the students and teachers

- Consider getting rid of the National Incentive and Philosopher Courses to bring more focus to the students