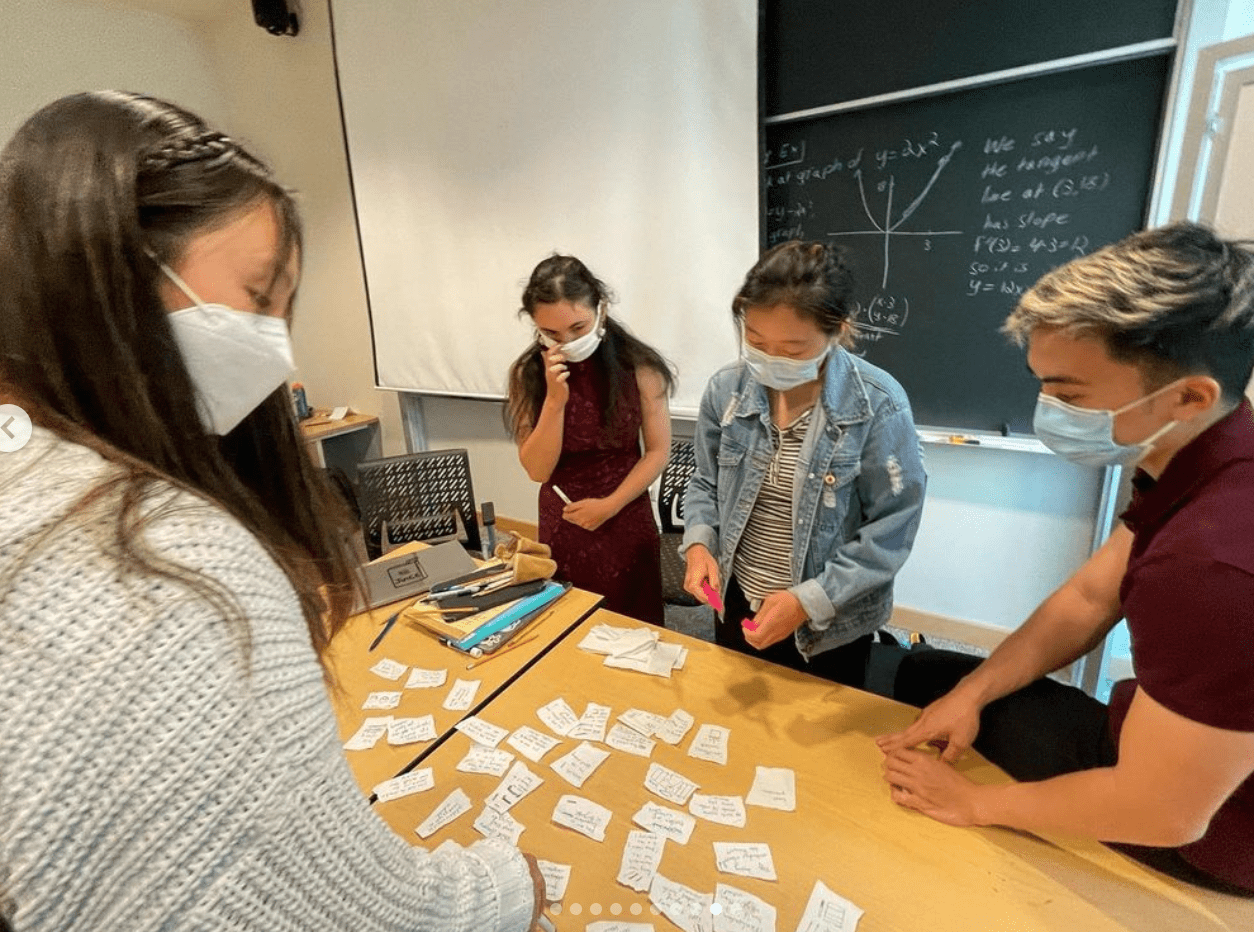

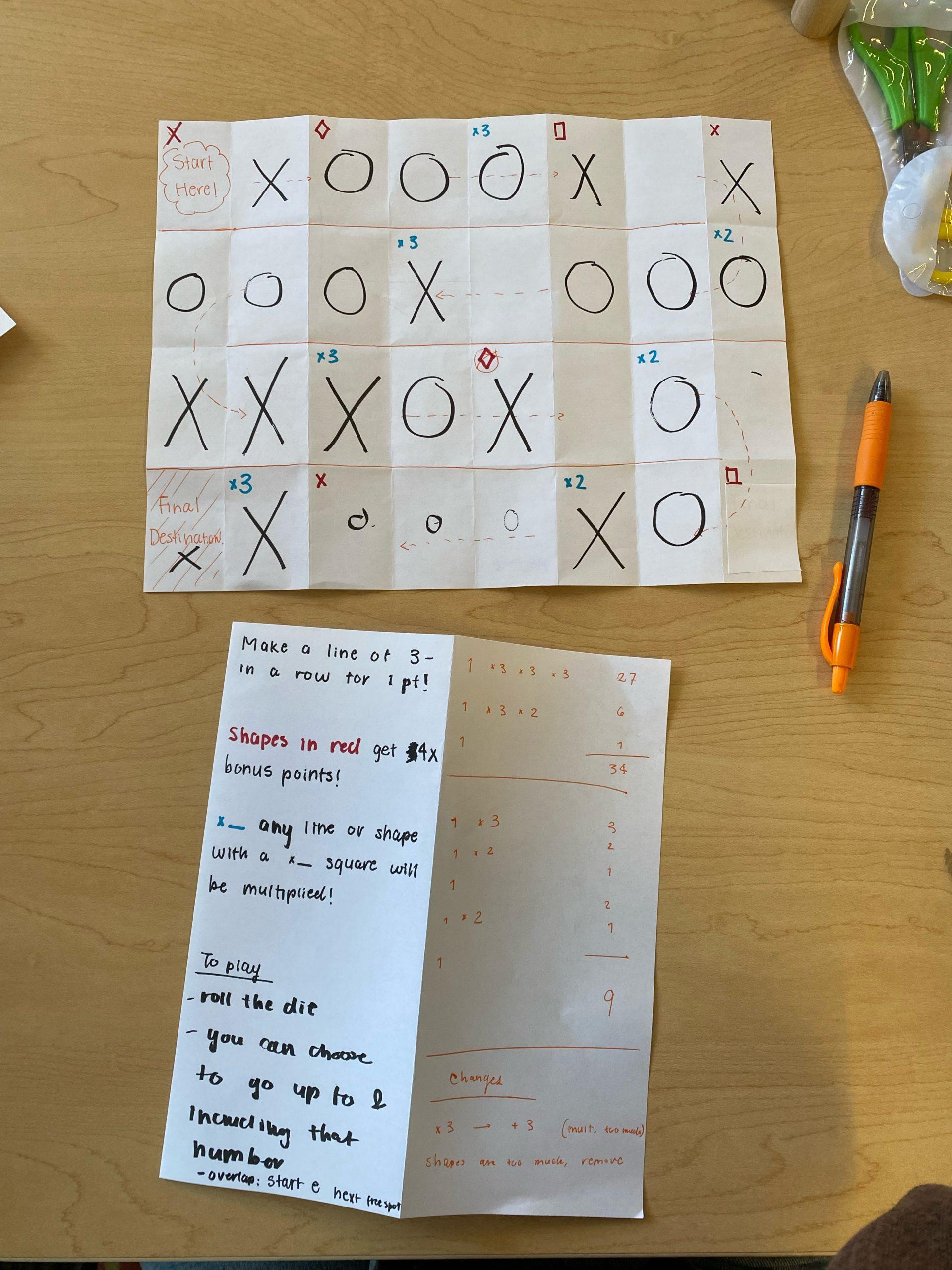

First day of class: make a version of Tic-Tac-Toe that would be engaging for Stanford students. Go.

This is what I came up with. As I was furiously folding and writing to finish my game within the time limit, I thought, “Wow, I’m really in a Stanford class!” — the type of class that makes you feel grateful for making it to such an incredible school.

I’d like to think I’ve come a long way since that first day of class when I met Christina, Nina, the TAs, and the rest of my fellow students. Before this course, I thought about game design as prescription: the designers construct something they think would be fun, and different groups of people will find it entertaining. Perhaps you can measure the success of your construction by the size of that group, but others might be content if it reaches a group at all.

I always knew that play was a teaching/learning tool, but I always associated it exclusively with what you learn through play as a child; I wasn’t giving myself enough credit for the learning I was capable of as a college student who plays games. But now, I’d like to think I give myself the credit, as well as acknowledge it more in others.

I really enjoyed thinking about the overarching theme of scope across the different concepts we learned. Particularly, I loved talking about the 8 different types of fun in games and applying them to the different games I played for the rest of the quarter (I still think about the different types of fun when I’m playing small things like GamePigeon or Pokemon Go). Discussing this in class taught me that your game doesn’t have to do everything. In fact, it really shouldn’t. I learned to think more intentionally about the type of fun I wanted my audience to have instead of just worrying about whether or not my game was Fun with a capital F.

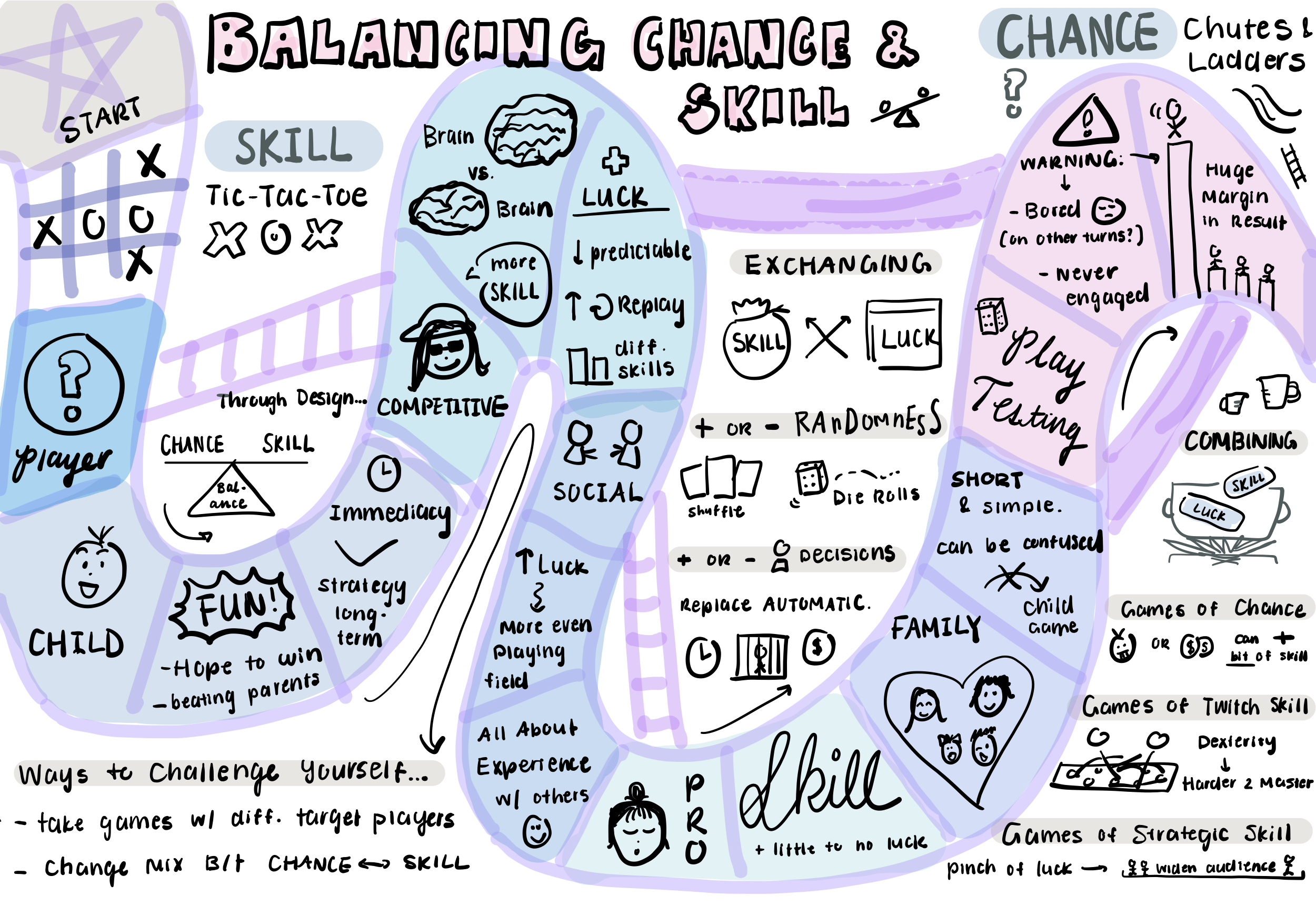

Another concept that stuck with me was the idea of balancing chance and skill in a game. Below is a chutes-and-ladders-themed sketchnote — another awesome skill I cultivated! — I made on this idea. As with any game, you have to consider your audience when balancing the recipe of how much chance goes into a game vs. how much skill. For instance, a Social game would need more luck to even out the playing field so you could focus on the other people you’re playing with, whereas a Pro game should be overwhelmingly skill-based.

The biggest challenges I experienced were all social – namely how to take playtesting feedback in a non-personal way and the idea of open team feedback. After pouring so many hours into each iteration of the game, it sometimes stung when playtesters made a negative comment about a feature that was entirely up to me or didn’t understand something I was really attached to. But that’s the thing about the creative process: you’re not creating only for yourself! People will play these games, and I should really listen to the people who’ve been kind enough to playtest them for me. I learned over time not to take things personally and be able to incorporate feedback in a grateful way.

I was also somewhat surprised when I learnt that we would give feedback to our teammates non-anonymously. Whaaat? And we had to say what to stop doing and what to start doing? But after the first feedback form, I was thankful for this opportunity. It encouraged us to communicate more openly for the next project and was a great chance to see feedback from real people; it wasn’t merely a mysterious comment that could hide behind the anonymity.

And I came out better because of it. I feel so much more confident stepping into any team or work environment; I have a much better feel for my own voice and what I bring to the table. I’ve also learned to communicate more openly, which involves both speaking the truth and being able to take it.

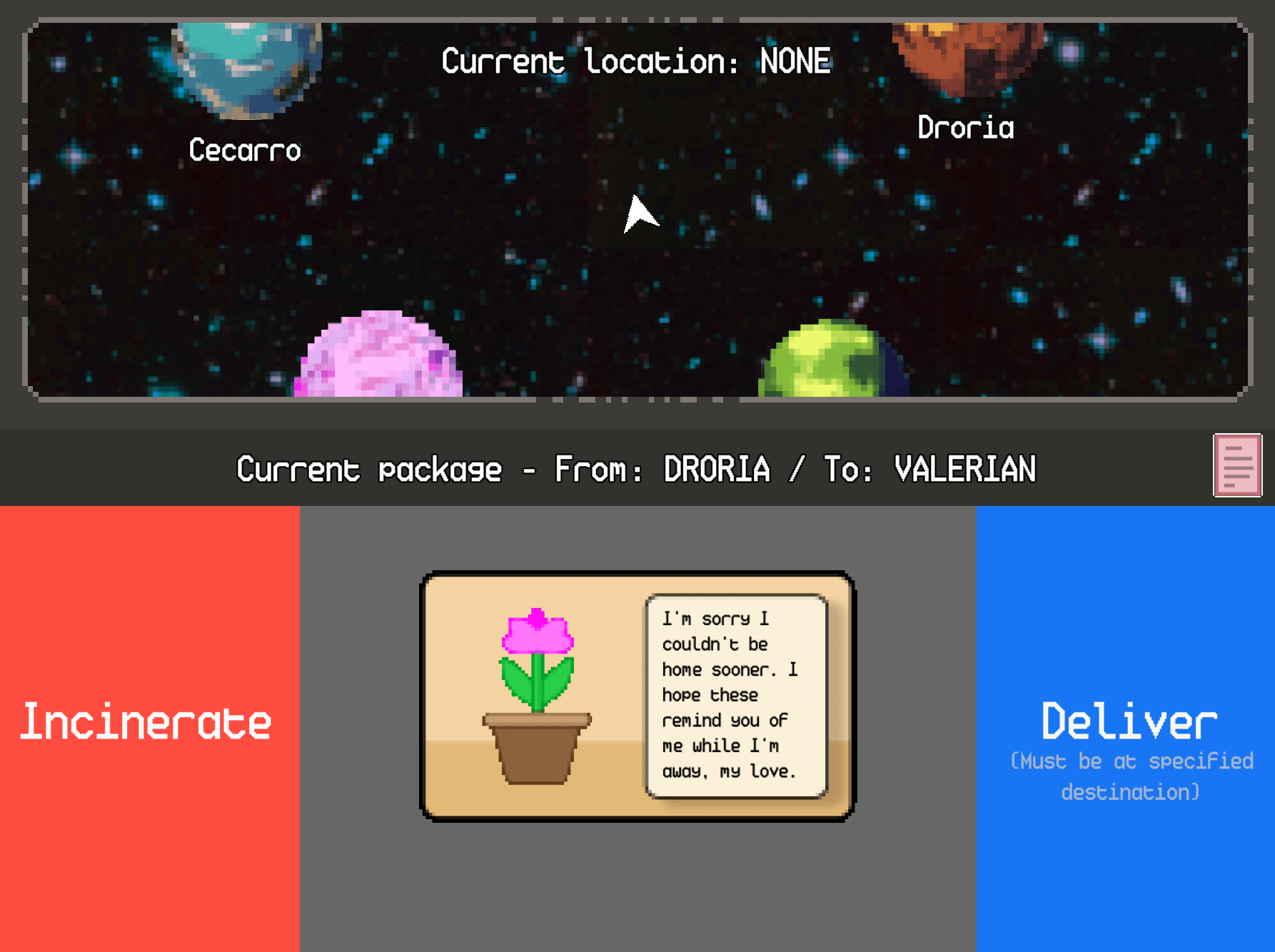

Thanks to my team, we’ve ended here, with our team’s second project, SpaceMail:

(Curious? Play SpaceMail here!)

I’m so proud of the work I was able to do alongside others, but know that learning game design is going to be a longer journey — and I’m excited by this. Next time I dive into a challenge like this, I’d like to playtest on a far more diverse set of people, particularly those who are differently-abled. Since I nor my teammates were differently-abled, we had to turn to research and, in part, assumptions about what would be best in our design for accessibility. But history has shown that this is never the answer, and we need first-person opinions from those we are considering.

I’d also like to experience game design on a larger team — I can imagine it’s more chaotic, but I’d be interested in learning how to work on a team of a larger size and hearing how many more ideas come together into something cohesive and wonderful.

Before this class, I never imagined myself working in the game world. But what I realized throughout the course was that I had played a lot more virtual games than I had given myself credit for. I was confining my idea of “video games” as just Mario Kart (which I love) and shooter RPGs. But I know games, I love games, and now I can create games. I know this now, and I’m really excited to talk to more and more people about what life is like when you’re making games.

I’m so grateful to this class for opening the door to this world of awesomeness. It brought back the childlike wonder I had and taught me not to be afraid of “Why,” “How,” and “How can we make it better?” at every opportunity. Thank you to my amazing teammates, to everyone who playtested along the way and gave phenomenal feedback, to Jean (who was always willing to lend us a kind, helping hand), and to Christina, who inspired it all.