By Nancy Hoang, Rebecca Jia, Malika Kanatbek,

Walker Stewart & Chu Zhang

Artists’ Statement

In making “Dorm Break,” we intended to create an escape room experience that would be familiar to current and former college students, while still ensuring the core of the game was clear and accessible to all players. We went about accomplishing this goal by hosting the game in one of our team members’ dorm rooms, giving the players the authentic experience of sifting through the items that exist in a dorm room to find those that are relevant to solving the ultimate puzzle. Beyond the setup of the game, the sequential nature of the five puzzles the players need to solve in order to escape ensures that the players are working together attempting to problem solve, which we felt cultivates fellowship. Additionally, by having the final objective – unlocking the phone – relatively clear at the start of the game, we felt that the players would have a clear understanding of the scope of the broader puzzle they were attempting to solve. Overall, we hoped to design an experience that fostered critical thinking and teamwork throughout the escape room.

Concept Map

https://drive.google.com/file/d/12SyiMbmaHardTakDim9JmNoYf_FpzNWa/view?usp=sharing

*** Linked to help with visibility***

Design

For Dorm Break our team aimed to recreate a space that was reflective of a student’s living space by setting the scene in an actual dorm room. In addition, our goal was to utilize objects that would naturally exist in the space, which is why we forgoed using things such as a physical lock and limited the number of objects we would have to collect or create. To set the mood of the room, we turned down the lights and left on a red LED in order to capture a more intentional and mysterious environment, since the premise is driven by a student who was purposefully leading their friends into solving a mystery. While our initial playlists capture this mystery, we opted to instead play the Suits’ soundtrack since the final destination was a Suit’s audition. This allowed for the space decor to reflect back on the narrative and character itself, who is interested in Suits and most likely listens to the soundtrack. Given the nature of the student, we attempted to hide all of our clues in items that can typically be found in a dorm room including laptops, iPads, food, and project or homework materials such as a poem for an English course or a 3-D frame from a PD course.

Our clues were guided by a to-do list, which fits the character’s student background and the list structure guides players to input clues in the order that they found them. In addition, it is an inconspicuous way of starting off the escape room with the text. When designing for difficulty, we opted for a range of levels. We had harder clues, such as the phone number to laptop password for a higher satisfaction level and easier clues like the hidden snack puzzle to help the players have early successes and motivate them to continue. For our medium puzzle we programmed a map of the Stanford main campus to display a number when two spots are identified and their ranges overlap. This allows for an introduction of novelty while still acknowledging the campus space itself as a reminder that this was a story about a college student. Lastly, in our iterations, we took out aspects that made the game escape the space with outside knowledge such as not using references to popular media.

Core Concepts from Class

Examining the seven formal elements in the context of “Dorm Break,” we can see how each is employed. The players, and the relationship between them, can be a range. Theoretically the game can be played by one person, but this would take away the relationship aspect of the game. The objective is clear from the start: open the phone to escape. Being an escape room, the rules and procedures are few – the biggest rule during our final playtest was not to open the drawers that were duct taped. This ties into the boundaries of the game, which include the duct taped areas as well as the walls of the room. The game is self-contained. Finally, the outcomes possible are successfully escaping and failing due to either being unable to solve a puzzle or running out of time.

In designing an escape room, our final product contained primarily interaction arcs with each individual puzzle containing an interaction loop. Opening the phone at the end is the clearest example of an interaction loop, as the players are given the screensaver and can easily discover the fact that they need 6 digits to open the phone, but have to take actions using the results from all of the clues to attempt to get the code. Every team that playtested our game incorrectly guessed the passcode at least once, which allowed them to get feedback and learn from their mistakes. Interaction arcs were primarily utilized to move the narrative of the game forward as the players moved from the clue to call JONES onto the computer and so forth. This choice was intentional, as it allowed the narrative of the missing friend to develop.

The overarching narrative of our game was clearly an embedded narrative. This is the case because “Dorm Break” is a story as a body of information that the players go about solving as they move through the escape room. At the beginning, all they know is that they have a missing friend, but as the story progresses the players find out more and more about the narrative, when by the end they get the full picture of the new season of suits being in production and their friend being in it. This comes after one of the clues is to watch a portion of an episode of Suits.

There is a baseline expectation that players of our game have the requisite background knowledge to use an iPhone and computer, beyond that with the opportunity for hints on the puzzles the game is quite accessible. To onboard players, we tell them the beginning portion of the story of the missing friend and the basic rules of not disturbing the personal items in the room before allowing them to go in. By leaving the phone and to-do list on the floor, we make it clear to the player that those are items that they should be looking at as they begin to attempt to solve the mystery.

The tone of our game is mysterious. We cultivate this in a few different ways, namely by closing the blinds and putting the game in dark lighting and our choice of music. As such, the objective for the players is to solve the mystery.

Playability

Our escape room is based on both digital and physical elements. One of the puzzles, for example, requires a player to manipulate a digital map on an iPad to locate a certain number. Moreover, to complete certain challenges players need to utilize laptop and mobile. Other puzzles are connected with physical elements such as papers, plants, and snacks. At this point, our game is bug-free and all of the components smoothly operate. However, we achieved that by constant iteration and playtesting.

By stating the rules at the start, we provide clear guidance on how to play the game. Overall, the game is intuitive because we clued everything and removed ambiguities. We made the logical correlation between the puzzles and clues.

Dorm Break is a game consisting of a series of puzzles that act as progressive milestones toward solving the overarching challenge of the escape room. When designing our game we aimed to put ourselves in the player’s shoes and ensure that all the puzzles were balanced and fair. Our goal was not to trick, mislead or put players at roadblocks to ensure a humbling defeat, but to create a fair gaming experience. However, fair does not mean simple or easy, it means the players have all the available resources and it’s up to their intellect and skill to win. The puzzles in our escape room are inspired by the routine activities of a regular college student. We designed the riddles with specific hints to lead the players in the right direction.

During the course of the development of our escape room we used MVP to find out whether the game concept would work. Our MVP had the essential feel of the completed game but lacked certain other components that we eventually incorporated throughout the development process. Our MVP underwent consistent revisions and iteration. The results of playtesting and ongoing feedback pushed us in a certain design path that helped us create a completed product.

Based on the final playtest we discovered that our game was able to get the players acclimated to the escape room quite fast. It was clear to them from the beginning that they needed to figure out the passcode of the phone from the to-do list. Once the players realized what they needed to do, it became their game. They got the preamble over as quickly as possible and jumped straight into the guts of the game. We also designed it in a way that players learned by playing it, discovering clues, and solving challenges. We were able to blend the “tutorial” into the game and enabled players to always revisit onboarding-related information.

Playtesting and Iterations

Playtest and Iteration #1

Playtest objective:

The first playtest was performed in class, with four or five classmates who served as our playtesters. We were testing for the following in this playtest:

- Does each puzzle make sense, or were some confusing?

- Were any puzzles too hard or too easy?

- Is the setup of the game easy to understand, and does it fit with the theme?

Feedback, Issues, and Responses

Many aspects of our game went well. First, the players correctly noticed that for the video puzzle, that they were supposed to single out the numbers in each of the clips. They also figured out the phone puzzle efficiently. The players told us that they liked the idea that the items of the to-do list was the order of the password on the laptop.

In terms of what didn’t go well, it was a little bit confusing for the players to keep track of the puzzles, because we just had them on a laptop in tabs, and we didn’t print them out, so we noted that we would print out the puzzles next time, because it is understandably hard to keep track of puzzles when not all of them are in front of the players. We also got the feedback that it didn’t make sense for the laptop to be in the laundry hamper, and that maybe it was better for it to be on a phone, because leaving a phone in a laundry hamper seemed more believable. Because we agreed with this statement, we also made a note to make the password be on a phone instead. Although they liked that the to-do list was related to the passcode, the players took a while to figure out this connection, and they also gave us feedback that they wished the connection between the passcode and the to-do list was more clear; since we believed that we had hints built into the game that made this connection clear, and since this was our first playtest, we decided to see if the time it took to make this connection was an anomaly, or if this was a more serious problem, so we didn’t immediately address this feedback concern.

The players also had some problems with the journal entry/map puzzle. After they solved the map puzzle, the text that appears when one taps on the dot is “foo” and this confused the players, because it wasn’t a number, so they thought they weren’t done with the puzzle, and kept trying to “solve it,” even though there was nothing else to solve, so we also decided to change this and make the text be a number instead of “foo,” so players wouldn’t waste time with a puzzle that was already solved. They also had trouble noticing that you can move the circles on the map by dragging them and the interactivity of the map in general, so we decided to try to improve this aspect as well so that players could spend more time on actually trying to solve the puzzle, rather than trying to figure out how to interact with the interface. To do this, we included instructions on how to interact with the circles.

Additionally, we originally had a riddle puzzle, but a player figured out this puzzle immediately, because they had heard it before, so because it was so immediate and not a challenge at all, we decided to discard this puzzle and come up with a more challenging one that took a bit more time. Moreover, the players had trouble with the video puzzle, because although they noticed that they were supposed to pick out the numbers that were said in the scene, they got confused, because one of the scenes had so many numbers said in succession, and they weren’t sure if they were supposed to write down all the numbers from the scene. Because it would have taken a really long time to try all the possible combinations of including and excluding certain numbers to solve the puzzle, we decided to fix this and only include scenes where one number was said. They were also confused about having to add the numbers that were found in the video to get the answer to this puzzle, and we recognized that we didn’t make this too clear, so we decided to come up with a way to indicate/hint at this for the future playtests.

To balance the game for our target audience of about 12+, we made sure to have puzzles that varied in the level of difficulty. For example, the phone puzzle was designed to be the easiest one, and we got feedback that although this puzzle was the easiest one, they liked having it in there to feel “smart” and to provide them more motivation to keep going; they thought it made the game more fun. We also had games of greater difficulty that more advanced players could enjoy, such as the journal/map puzzle, and the video puzzle, and players expressed feeling satisfied once they solved these as well. We also included different types of puzzles to balance the game for players with different skillsets. For example, the video puzzle was about noticing commonalities between the scenes (numbers), while the phone call puzzle was about figuring out how to convert letters to digits. By including games of different types and of varying levels of difficulty, we made sure that we accommodated various types of players so they could enjoy our game; players with one type of strength could shine at some points, and they could seek help from players with a different type of strength in another area at other points of the game.

We intended to focus on bringing the narrative, challenge, and fellowship types of fun to players. The players expressed that they liked the concept of the game, so they seemed to have enjoyed the narrative type of fun, and the dorm-themed objects and puzzles we had in the game contributed to this type of fun. Additionally, the players experienced the challenge type of fun, because they said they really enjoyed the phone puzzle for example, and they also expressed happiness and excitement when they figured out the entire escape room. Lastly, they were working on all of the puzzles together, and for some puzzles, one player really shined and helped the others, and for other puzzles, another player shined and helped the others; consequently, they also experienced the fellowship type of fun.

Playtest and Iteration #2

Playtest objective:

The second playtest was performed in class, with four or five classmates assigned to be our playtesters. This time, we printed out the journal entry and video project instructions and also had the snack puzzle as well as the poem puzzle ready for testing. Since we had all of the puzzles ready, the main questions that we wanted to answer with this playtest are focused on playability:

- For all puzzles

- Is the difficulty level appropriate?

- Core puzzle

- Is the relation between the to-do list and the phone’s password clear?

- Does the final revelation make sense on a phone? (We replaced the second laptop and used a phone instead for this iteration)

- Journal puzzle

- Is the intractability of the map clear?

- Is it clear when the players make it to the end of a puzzle? (i.e. they don’t try to go even further on the same puzzle)

- Video project puzzle

- Is it clear what to do with the numbers obtained from each clip?

- Snack puzzle

- Are players able to realize that the frosted cookies are special?

- Poem puzzle

- Are players able to realize that the black out board can be aligned to the poem pages? And can they align them correctly?

- Is the pop culture reference from the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy appropriate?

- Is the message revealed from aligning the blacked out board and the right poem page understandable?

Feedback, Issues, and Responses

For this playtest, we had all the puzzles ready so we were able to test the entire escape room prototype, though not in a real dorm setting. From the start of the playtest, we found that the players immediately started picking up random objects and trying things out. They did take a cursory look at the locked phone and the to-do list as well, but didn’t seem to realize that the phone was the ultimate objective. They also did not seem to realize the relationship between the locked phone and the to-do list. This led to some confusion about how to get started and what to work towards. Our goal is to have the players immediately realize that they need to unlock the phone and that the to-do list is the key to solving the passcode. So for the next iteration, we decided to arrange the puzzle items in space more strategically. We decided to put the phone and the to-do list together on the ground in the middle of the room so that they are the first things that players will notice as they walk into the room. Also, this time there was not much difficulty about keeping track of the puzzles, since we printed the puzzles out instead of having them on a laptop in tabs.

Though we didn’t have any issues with the phone call puzzle in the first playtest, our players for playtest #2 had some problems with it. One issue was that the players thought there must be a hint or clue hidden physically on the phone itself, instead of the person who they needed to call, because the phone was not actually operable. After the playtest we also got feedback that the physical phone prop wasn’t necessary and instead could be confusing since they could also figure out the password using any phone dial pad, including the one on their own smartphones. We didn’t decide to take out the phone prop, because we reasoned that the phone was a standard item in Stanford dorm rooms and wouldn’t seem as out of place as it would be on a table in a classroom. We decided to observe some more playtests while not requiring the phone prop to be used. The players were able to get the puzzle in the end due to the password hint on the locked laptop, but they tried to type the name of the person to call in letters multiple times until we intervened and rewrote the to-do list item to imitate a phone number format: “Call (XXX) TIM-JONES”. But with this hint, they thought the password was all the digits corresponding to the whole name Tim Jones, instead of our intended password of digits corresponding to Jones only. We rewrote this hint again to cross out the portion of TIM and they finally got it. This playtest experience led us to make a plan to rework this puzzle to be less confusing. In our next iteration, we tested making the to-do list item say “Call (XXX) XXX – JONES” and also included in the laptop’s password hint that the password is all numbers.

After the first playtest, we improved the map for the journal puzzle to include instructions about how to move the circles, however in this playtest the players still had trouble figuring out how to interact with the map. One of the main reasons was because the players didn’t notice the instructions and zoomed in even more, resulting in the instructions to be out of sight. After finally zooming out and seeing the instructions, the players were able to link the journal entries to the map and solve this puzzle. We believe the intractability of the map is crucial for a smooth game experience, so to further eliminate any mechanical problems with the map, we decided to revise the user interface of the map again for this iteration, this time highlighting the instructions with a blue outline and bold letters. Also, we made the instructions’ position fixed on the page, so that the players wouldn’t scroll the instructions out of sight. For this playtest we changed the answer to this puzzle to be a number. This was interpreted immediately as the end result for this puzzle, proving that this change successfully resolves the issue that we found in playtest #1 where players didn’t know when the puzzle ended.

In this playtest, one player initially thought that the video project instructions with the timestamps are a puzzle that would lead to the password for the locked laptop. This confusion seems to be an unnecessary distraction to the game, so we made a note to clarify in the to-do list that the video project is to be done on the laptop. Another thing that we noticed was that someone was guessing that the starting point of the video when the laptop was opened might matter. Since it doesn’t actually matter, we updated our game setup procedure to make sure that the video starts from the very beginning to avoid any false impressions. For this playtest, we updated the video project instructions sheet to include an additional instruction to “stitch up” all the scenes, and wrote out a sum formula using the scenes to hint at what the players should do with the numbers from the video. This hint worked well and the players were able to sum up all the numbers to get the final number.

In this playtest, we tested the poetry assignment puzzle for the first time. While the playtesters liked the mechanics of aligning the black out board with the poem pages, they were confused about a few things. First of all they were unsure which side of the black out board should be used. We decided to intervene and tell them which side should be up since we felt like it was unnecessary ambiguity. Second, though the black out board could only be aligned with one of the pages to show complete words, the players thought all three pages must matter and should be used. We initially included a book cover printout for the book A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Universe with a scribbled note saying “What’s the meaning of life” and numbered the poem pages. The idea was that this would tell players that only page 42 matters. However, this was not received well. Only one player understood the pop culture reference and the others expressed dissatisfaction that the puzzle required prior knowledge of something unrelated to the game. We completely agree with this feedback, as we’ve learned that a good puzzle should always provide the player with everything they need to solve the puzzle. Using pop culture references is unfair to players who don’t already know them and can be isolating. Third, after getting the correct message from the right poem page, the players were still unsure what to do because the message didn’t really make sense as a whole and only a few words actually mattered. To address these issues and feedback, we decided to remove the pop culture reference completely and instead use unique cutouts on the black out board and the poem pages to indicate which page is the right one. We also decided to highlight the blanks for the words that matter on the blackout board to clarify the clue.

Another new puzzle we tested this time was the cookie puzzle. The players seemed to enjoy the unexpectedness of being able to “have a snack” during the game. This puzzle was on the easier spectrum of our game — the playtesters were able to quickly figure out that only some cookies had frostings and spelled out the number for this puzzle quickly. To make this puzzle slightly more challenging for our targeted audience, but still easy enough to balance out the difficulties of puzzles throughout the game, we decided to add one level of indirection for our next playtest: the cookies would spell out “quack” and there would be a plastic duck with a number will be taped underneath it in the room.

In this playtest we also tested the final revelation. We set up the locked iPhone to show a message to the players when it is unlocked, revealing to the players that the missing friend was frustrated with his mundane daily life and was pondering the meaning of life. We meant the ending to be vague, and for the players to be able to imagine their own ending for the missing friend. One possible ending we provided to the players was that the missing friend went on a journey to find himself. We did not receive much reaction to the final revelation other than a chuckle or two when they clicked open an embedded link that led to a quirky playlist. We made note to revise this final revelation and balance the narrative and the challenges more.

Overall, the playtesters really enjoyed our game and expressed satisfaction whenever they successfully solved a puzzle. They also seemed very excited when they finally put everything together and unlocked the iPhone. Nevertheless they did give feedback about how it was annoying to have to enter a super long password. Since having to enter an extremely long passcode into a small phone is frustrating and negatively impacts from the game experience, we decided to revise the final passcode a bit to not only shorten it but also add in another mini puzzle that ties all previous puzzles together.

Playtest and Iteration #3

Playtest objective:

The third playtest was performed in a real dorm room, with about four classmates from a different team. Our objective for this playtest was to answer the below questions:

- Is the connection between the phone passcode and the to-do list clear?

- Are the puzzles clear and free of distractions?

- Is the space utilized well? Or are there too many distractions?

- Does the narrative go well with and are balanced with the challenges?

- Does our playlist and lighting choice reinforce the theme and mood of the game?

Since this was our only chance to properly test our game core in its entirety, we wanted to focus on the overall game experience in this playtest.

Feedback, Issues, and Responses

The modifications that we made based on our previous playtest improved the playability of our puzzles immensely. There was significantly less confusion in our game mechanics (such as how to interact with the map in the journal puzzles, and how to align the black out board and the poem pages), and also fewer distractions that led players astray. The game flow also was much smoother than before. The players were able to quickly realize the importance of the to-do list and how it is related to the locked phone from the start.

Our revised narrative where the missing friend was a huge fan of Suits (the same tv series used in the video project puzzle) and was actually away for a secret casting for a new show being produced by the creators of Suits won some laughs from the players. The players liked how we tied the final revelation back to the puzzles that they’ve solved. We also observed that the players seemed to enjoy our playlist and received good feedback about how we set up the dorm room.

However, there were still some things that needed improvement. Most of our hint system worked very well, teaching players what to look for and what to do with the numbers. However, we used the Macbook’s built-in password hint for the laptop and unfortunately this time our players didn’t know how to trigger it. In our previous playtest, the players saw the hint after trying too many incorrect passwords, but this time the players were hesitant to try too many incorrect passwords in fear of being locked out for some time. We intervened and showed them how to see the password hint to help them make progress. To address this problem, we reworked this hint to be a tiered hint. The first hint (“Who did I just call?”) would be displayed on the MacBook screensaver to get the players started without requiring any knowledge of MacBook password hints. The second hint would be a complementary hint (“numbers only”) that still utilized the MacBook password hint for players who need additional help.

After playtest #3, we modified the final iPhone passcode to be a concatenation of the sums of each digit in the numbers from all the puzzles. This leads to a shorter 6 digit password that is customary for iPhone passcodes. We modified the iPhone’s screensaver to also include five blanked out formulas for calculating the sum of the digits for each of the five puzzles. This screensaver hint is intended to help players understand what to expect from each puzzle and what to do with the numbers from each puzzle. The players apparently were uncertain about this hint because there were only five formulas while the iPhone passcode had six digits. Because of this, the players had trouble understanding how the to-do list puzzles linked to the locked iPhone. To address this issue, we decided to add blanks on the results side of the formulas to indicate how many digits are expected from each puzzle.

Our space utilization mostly hit the marks. We strategically placed items necessary for the same puzzle close together while keeping each different puzzle slightly far away from one other to avoid confusion. The locked iPhone and the to-do list was placed at the center of the room and as expected caught the attention of the players immediately. One issue was with the placement of the cookie container for the snack quiz. There were several different snacks in the room and there happened to be one bag of candy that was placed away from all the others. The players mistakenly thought that bag of candy was the puzzle. We believe that to address this problem we would have to clear away unrelated snacks to reduce the distraction and confusion.

This playtest in general was very successful as a whole despite the above issues found. The players seemed to have enjoyed exploring the space, solving each puzzle, and finally putting everything together. The players are all very engaged and there were a lot of emotional reactions of excitement, surprise, and delight as they progressed through the game.

Playtest and Iteration #4

Playtest objective:

The fourth playtest was performed in class, with about four classmates that served as playtesters for each of the two playtests we did in class. We were testing for the following in this playtest:

- Is the connection between the phone passcode and the to-do list clear?

- Do the password hints for the laptop password give the right amount of help to the players?

- How do the players interact with the video challenge?

Note that one of our group members was sick, so we were unable to test the poem puzzle for this playtest.

Feedback, Issues, and Responses

For things that went well, it was clear to the players in both playtests that they were supposed to try to figure out the passcode of the phone from the to-do list, so this was an improvement from previous playtests. The new password hint screensaver on the laptop in addition to the further hint about the password being numbers only was very effective in helping the players figure out the laptop password. The player who worked on this puzzle gave feedback about how he liked this hint system after the playtest ended. Playtest group 2 also commented that they liked the effect of the intersecting circles and they said they thought it was really cool. For the snack challenge, the groups correctly noticed the frosted cookies, and they took them out, but some of the other members of both groups noticed the number on the duck before they were able to make the connection between the duck and the cookies. However, since we didn’t set up the game in an actual dorm room, the duck was sitting right in front of them, so it was much easier to notice, so in general, noticing the duck right away shouldn’t be a problem.

For the video challenge, the second group liked the trickiness of the challenge. However, the first group needed a slight hint of us pointing out the built-in hint at the bottom of the page to add the numbers, but we believe that they could have eventually figured this out just by reading the page again one more time, since the second group was able to immediately recognize this. For the first group, we also had to point out the phone screensaver (this is the built-in hint), but because the second group and all other groups noticed it, we believe that if this group took a bit more time to look at the phone they would have realized it on their own. The first group also gave us feedback that they would have liked to have intervals for the timestamps, so they knew when to stop looking and so they didn’t watch the video for too long. We believed that this was a valid suggestion, since we didn’t want the group to try to watch the entire episode of the show, so for the second group, we included intervals for the videos, and this helped them get that they were looking for numbers and it helped them know when to stop the video.

After this playtest with the two groups, we found that there were very few major changes we needed to implement, because for the “finding the duck before making the connection with the cookie challenge” occurrence, we believe that if we had actually set up the game in a dorm room, this wouldn’t have happened (and indeed, this didn’t happen when we actually set up in a dorm room). Additionally, although one group needed a slight nudge of reading over the challenges (the phone passcode and the video challenge) again more carefully to notice the built-in hints, we believe that this is acceptable, because the players would have likely noticed this on their own given a bit more time, and this only happened with one group.

The players in both groups expressed that they liked the game, and they were delighted at the “answer” to the escape room, so they appeared to have enjoyed the narrative type of fun. Moreover, the players also experienced the challenge type of fun, because they said that they thought the difficulty of the games was good, and they also expressed visual excitement and satisfaction after solving each one. Finally, since they were working on the puzzles together, and since various individual players helped the group to succeed, they also experienced the fellowship type of fun.

Playtest Video: https://youtu.be/R_UI2XZkBPo

Feedback Video: https://bit.ly/3lU3dl7

Post-Mortem

For future directions and developments of the game, we believe that we could add to the story of the student “going missing” because they were filming a big Hollywood movie, and we could develop the game to include puzzles that fit with this theme. We believe that our escape room was refined to be a fun and enjoyable experience for our target audience, and we would be able to develop it even further in the future to experiment more with adding to the storyline and the theme, as well as developing more puzzles to go with this storyline/theme.

Final Playtest and Feedback for “Escape From Your Mind”:

As a team we tested “Escape From Your Mind” for our final playtest.

Rebecca’s Feedback

I thought that this game’s theme was very interesting as a concept, and I liked the ambiance of the room set-up. I also liked the artisticness of the room with the various paintings. I thought that it was nice that the puzzles could be solved with just one or two people, because this allowed the rest of the group members to go solve other puzzles.

Some feedback I have for improvement is that the map puzzle was a bit annoying to try to figure out, because we weren’t allowed to remove the paper from the wall that guided us to try to get the key out. Additionally, I thought that it was tough to try to make the connection that the box thing and the maze on the wall were connected, partially because of the fact that there was nothing linking them together, and because there were so many other random things in the room, I thought that the maze on the wall was also just another random thing.

Additionally, I liked the concept of the clock puzzle, but I thought that it could’ve been executed in a better way. To start, I think we had a hard time finding all of the clear cards that served as hints to solve the puzzle, and if we couldn’t find them, then we would essentially be unable to solve the puzzle and we would be stuck. I think placing the cards in places that are slightly more able to be seen would have been beneficial.

Moreover, for the logic puzzle on the table, there were extraneous boxes that were left once we solved the puzzle, and this made it hard to tell if we were actually done solving the puzzle or not.

Finally, the games themselves were a bit random in the sense that they didn’t really tie into the theme that much. I think the logic puzzle sort of tied into the theme, but I didn’t see how the maze puzzle or the clock puzzle tied into the theme of being trapped in one’s own mind. However, I still thought solving these puzzles was fun. Additionally, when we finally unlocked the room, I was a bit unsatisfied, because the room was more calming and less congratulatory. I think this is because there was no “mystery” to the game in the sense that we weren’t trying to find out how someone went missing, for example (in this case, the satisfying ending to the game would be to get the answer of why that person went missing). However, I enjoyed the gameplay experience, and I thought that the individual puzzles themselves were well-thought out overall.

Walker’s Feedback

Walking into the room I enjoyed the decor, I felt it did a good job augmenting the game’s narrative of being on acid and attempting to “Escape From Your Mind.” Likewise, the music chosen for the game was effective in accomplishing this as well.

Diving into the actual mechanics of the game, I felt that the three separate locks needed to open the final box led to our group dividing into sections to attempt to solve each puzzle individually, which I didn’t think was ideal. In addition, the puzzles didn’t seem to have any connection to one another, with the clocks and solving the riddle not really interacting in any meaningful way.

With that being said, each of the three puzzles were well thought out and enjoyable to play. I especially liked the narrative included in the clock and riddle puzzles and the intricacy of each. Each was complicated enough to force deep thought, but straightforward enough to allow for progress to feel like it was being made. On the riddle, one frustration I had was that once I solved it for each of the three people, translating the solution into the combination for the lock was quite convoluted, almost forcing the players to ask for a hint. The problems our group ran into on the clock puzzle were mostly self-inflicted – the poem clearly laid out everything we needed – and I feel like by addressing some of the other issues outlined above the clock puzzle when being solved by a full group without time pressure would be a great experience. Overall I really enjoyed the game, but felt that with a few small tweaks it could have been even better!

Additionally, in class I playtested excerpts from “Locked Door Office Hours.” Due to only working on two of the puzzles that made up the entire game, my understanding of the overall narrative is limited. That said, I enjoyed the initial puzzle of attempting to open a lock given a circuit diagram. For me, it was the appropriate level of complexity where it fostered discussion amongst the members of the group as to what the diagram was representing, while at the same time being straightforward enough that there wasn’t a feeling of spinning in circles.

The other portion of the game we playtested, the video and ensuing questions we answered was quite creative. There were certain elements of the video, namely the unique spelling of the deceased student’s name, that directly led to questions. I was impressed at the subtle emphasis on these elements. The emphasis wasn’t so overblown as to make the questions meaningless, but at the same time it was clear enough that I was able to remember most of the answers having only watched the video once, which I liked. The biggest area I saw for improvement was in the video, specifically in the sound as it was quite hard to hear at certain times even though there was relatively minimal background noise.

Malika’s Feedback

The most intriguing aspect of this escape room was its creative setup, which immediately immersed us into the game. The space was filled with artworks that was incredibly beautiful but caused confusion in my head. I couldn’t tell the difference between actual items and puzzles.

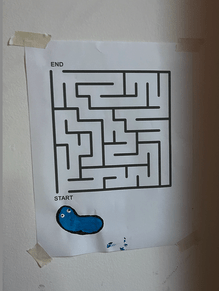

I was able to discover connections between the locker, box and the maze on the wall because they all have one thing in common: little blue worm.

Looking at the maze on the wall we needed to solve the box puzzle; however, it was a bit challenging because we were not allowed to move objects. Therefore, one player needed to look at the maze and give directions for another player who was solving box puzzle. I think it was fair because we got all the required resources to solve this riddle and needed to make a bit effort to complete it.

We all divided into sections to attempt to solve various puzzles and find all the keys for lockers. Some puzzles were too complicated and time consuming but very engaging. I wish we had more time so I would be able to deeply interact with each challenge. Everything seemed so fast that I event did not have to analyze all the correlations between each puzzle but we were able to solve everything together.

Chu’s Feedback

Overall, I enjoyed playing “Escape from Your Mind“. I felt that the theme and narrative about being trapped in a psychotic state of mind and trying to escape was reinforced nicely by the lighting, music, and props in the space. The puzzles were innovative and fun to solve, providing me with the fun type of challenge. I liked how space was utilized in this game. The maze puzzle required players to split into two teams, one standing at the physical maze and the other at the map for the maze. This separation of locations brings in a need for collaboration and fosters the fun type of fellowship. The logic puzzle didn’t really utilize space as much but the clock puzzle used space in a very creative way!

As for feedback about what can be improved, I think there were some distractions and confusion in the game that could be removed. For example, there were a lot of clocks in the room, which I thought must be related to the clock puzzle but was actually not related at all. Also, the dots on the clear card stack sort of aligned with the tip of the hands of some of the clock faces on the wall, making us think that was the right way to go. There were also extra columns and rows on the table form for the logic quiz that made me feel that we were missing something while we actually were not. Another interesting confusion was with the % sign in the logic quiz. Walker and I thought it meant the mod operator (as it is in many math and programming languages), but it was actually supposed to be division. Also we tried to do the math from left to right disregarding operator precedence. While operator precedence is important in math, when it comes to games where words are translated to digits in our heads, operator precedence can easily get overlooked. It would be great if the math expression was disambiguated to avoid confusion and mistakes that don’t seem necessary or related to the essence of the puzzle.

Another piece of feedback I would like to give is about the clear cards for the clock puzzle. I love the idea of aligning the clear cards together and then aligning the stack to the clock faces on the wall. I also like the hint system for this puzzle as well. The hint for checking whether we got the alignment right was a great touch. When I played the game, though I aligned the clear card stack with all the clock faces on the wall, I was not doing it correctly according to that self-check hint. The issue was that the clear cards had a blue outline and the nine clock faces all together actually matched the outline of the clear cards. I thought the clear card stack should be aligned to cover all of the clock faces. I didn’t think we should be sliding it over the clock faces slide-window style. I think there might be a subconscious thinking that matching up means outlines must match as well. Perhaps if the cards had no blue outline it wouldn’t invoke this common mindset.

Nancy’s Feedback

As a drug-induced theme game, I thought that the environment could not have been more perfect. I loved the way the boundaries of the game were blurred and yet bounded by the abstracted painting and randomly placed clocks. In addition, the musical touch at the start and change to calmness at the 45 minute mark was well thought out.

For the puzzles, I thought that having the three locks was a nice way to guide users in their overall process. It gave direction for players and made the puzzle very clear. It also allowed for groups to diverge and work on different puzzles at the same time.

For the first puzzle, they made a maze that I thought was incredible. It was so cool to have the magnetized box and the symbols linking everything together was perfect for demonstrating the connections between everything. It was also a perfect opportunity to create teamwork in an escape room, which can honestly sometimes be a more toxic environment. In the second puzzle with the riddle, I thought the problem was more intuitive to solve with the chart. However, the letter count at the end was not very intuitive and led to some complexities in the puzzle. By having a hint attached, I could see the game being more enjoyable. In the last puzzle, I thought this had a higher fun factor due to the nature of search. The poem and difficulty in hiding spots made for an enjoyable environmental experience. However, the final step was extraordinarily confusing, but so satisfying when we got the hint and figured it out.

I thought everything was extremely well thought-out and well guided. In terms of improvements, there could be more done on the hint system. Other than that, it was a fun and satisfying game.

Extra Credit

We were inspired by the escape rooms that we have experienced in the past; we wanted to build a game with a series of puzzles that would serve as incremental achievements to unlocking the overall puzzle of solving the escape room. To try to set ourselves apart, we wanted to focus on having a digital component to our game (the journal/map challenge) and we also were refining our game to be a very specific theme of being based in a dorm room and being based on a student’s life. We believe that our game is better, because it is an escape room that uses everyday objects of a typical student’s life as puzzles. The joy of the game is that it’s not overly flashy or “try-hard,” and even if the players are not college students, they would still be able to relate to the school-themed and everyday-life themed puzzles, giving a more immersive and relatable feeling to the narrative.

Our game considered players with different abilities in various ways. First, we made sure our various puzzles had different levels of difficulty, and we made sure that the puzzles were of different types. This way, players of various abilities and skill levels would be able to enjoy our game, and they would be able to help their team members using their strong points. Moreover, we made sure to try to make our game inclusive for people with disabilities. This was especially a concern for us for the video puzzle, so we made sure to have the option for the video to have subtitles for those who are hard of hearing, for example.

Once players have played our game, they can walk away with various takeaways. One subtle takeaway was directed towards our fellow Stanford students. Because Stanford is a school that heavily focuses on tech rather than humanities and the arts, we wanted to convey that one can also have a prestigious and respectable career in the humanities/arts, and we tried to emphasize this takeaway in our design process by making the ending/answer of our escape room be that the student made it big in a movie. Moreover, we wanted players to have the takeaway that each of them have various skills that are unique to them. We considered this in our design process by making the challenges be of various types, in order to cater to players that have different skills and allow all of them to shine.