Artist’s Summary

Dicepto Bio–the Escape–puts players in the seat of a Corporate America boardroom, on a mission to save the world from greed and deception by uncovering a fraudulent drug deal. You act as an employee of Dicepto Bio the night before the launch of the coveted drug Verataseum. The company awaits billions of dollars from a successful launch. But something strange happens – in an emergency meeting called by your boss, Amy Goodwill, things go unexpectedly. The CEO, Don Dicepto, calls her and you are locked in the boardroom. Soon, you discover that Verataseum is a fraud, but there is no way of proving the facts. Or is there? Your mission is to discover the secrets hiding within the room, secrets that will allow you to escape with the truth and save millions of lives.

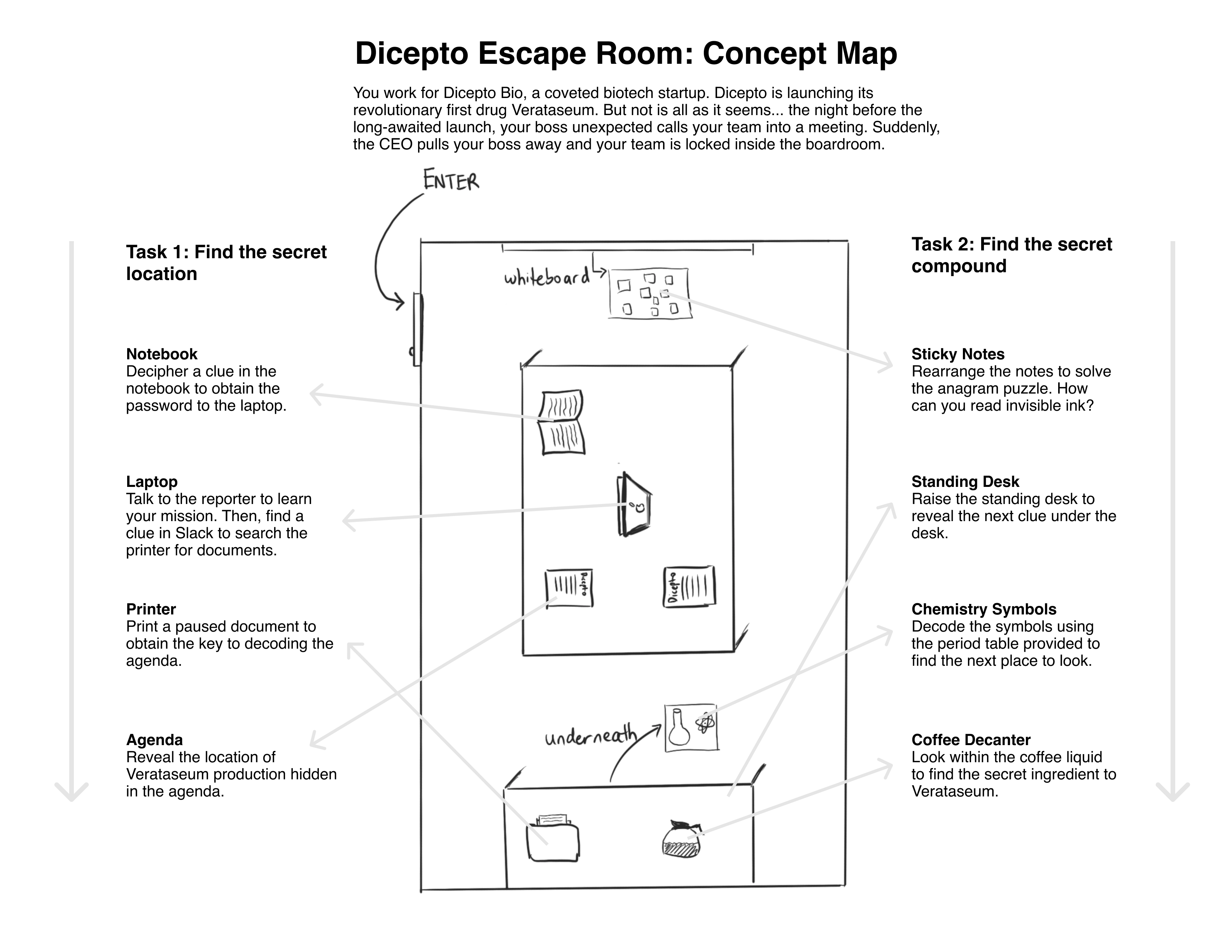

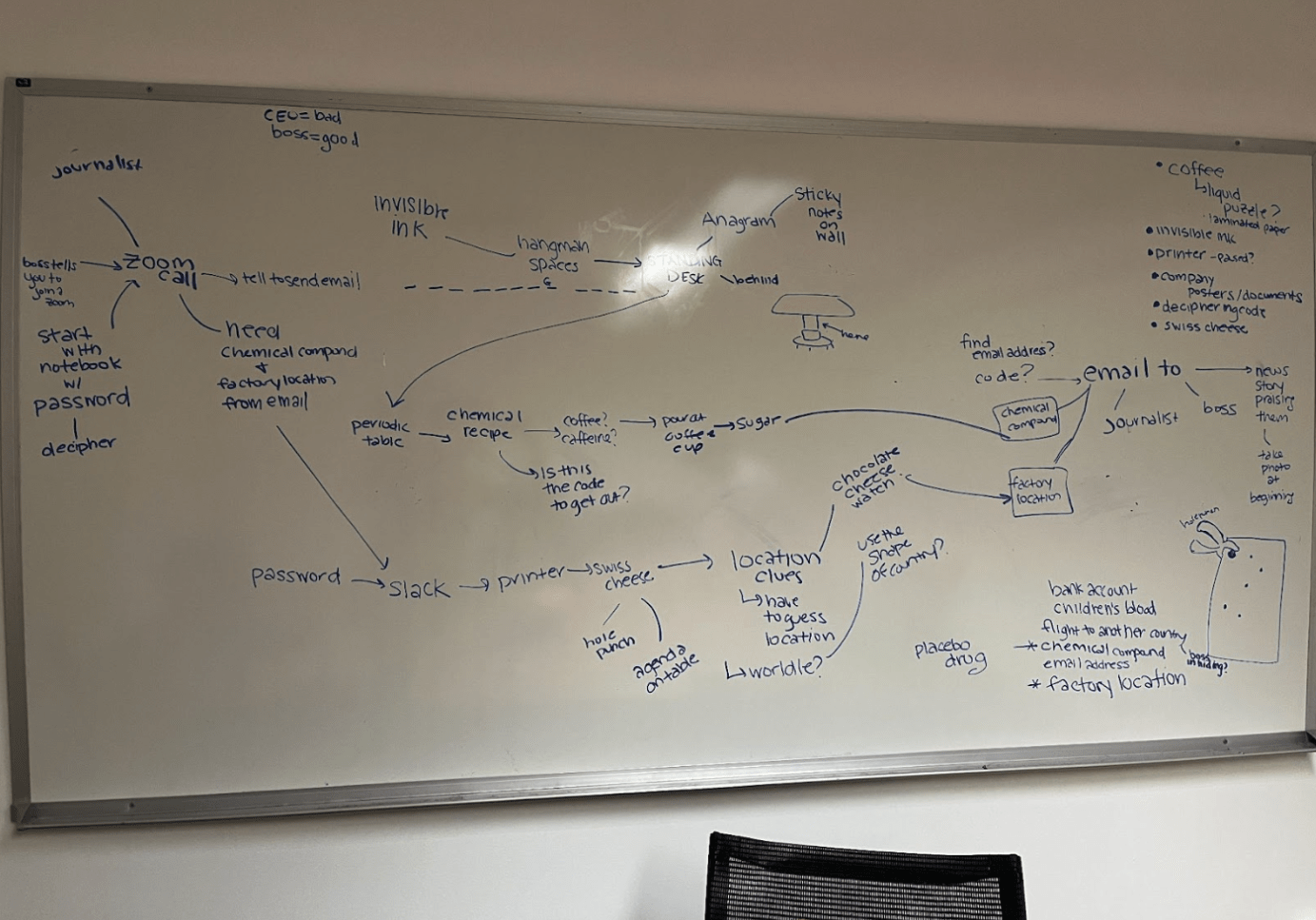

Concept Map

Initial Decisions

Our initial thematic decisions are viewable in our concept doc, which is available at this link.

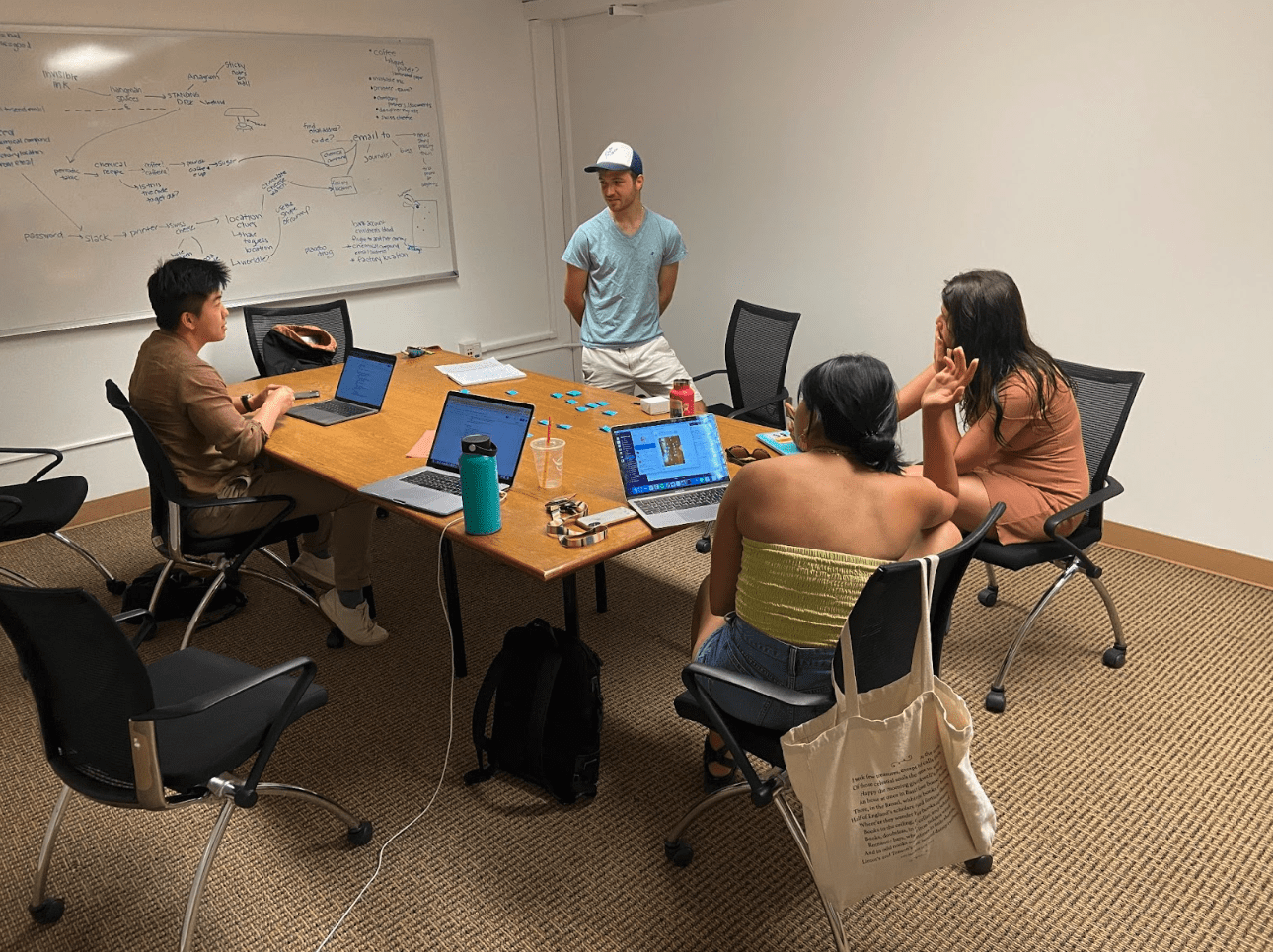

Initial planning meeting to flesh out game flow

Our first initial decision was to build our narrative around a deceptive, Theranos-like startup. When brainstorming primary emotions we wanted to evoke in players, we narrowed in on “ominous,” “curious,” and “liminal.” Our inspirations for tone came from shows like The Dropout, and games like Deduction.

We also planned our narrative around a mysterious meeting: we wanted players to enter into an ongoing dynamic between their “boss” and the “CEO” of our company. “Scams” were (and still are) entering pop culture in the form of buzzy news articles and new TV shows, and we wanted to give players the opportunity to experience the thrill of discovering and exposing a scam. We knew from the start that we wanted clues in the room to look like normal office supplies and equipment (a standing desk, post-its, etc.) but eventually lead to the origin of Decepto Bio (our company) and its lies.

Finally, we were sure that we wanted to touch on secondary themes of capitalism and patriarchy. An overarching goal we had was for innocuous (but still slightly eerie) clues to send larger messages about startup culture and be a slightly meta-commentary. For example, we knew we wanted to use Slack (which is popular at corporations and here at Stanford) to conceal clues about corruption.

Playtesting Summary

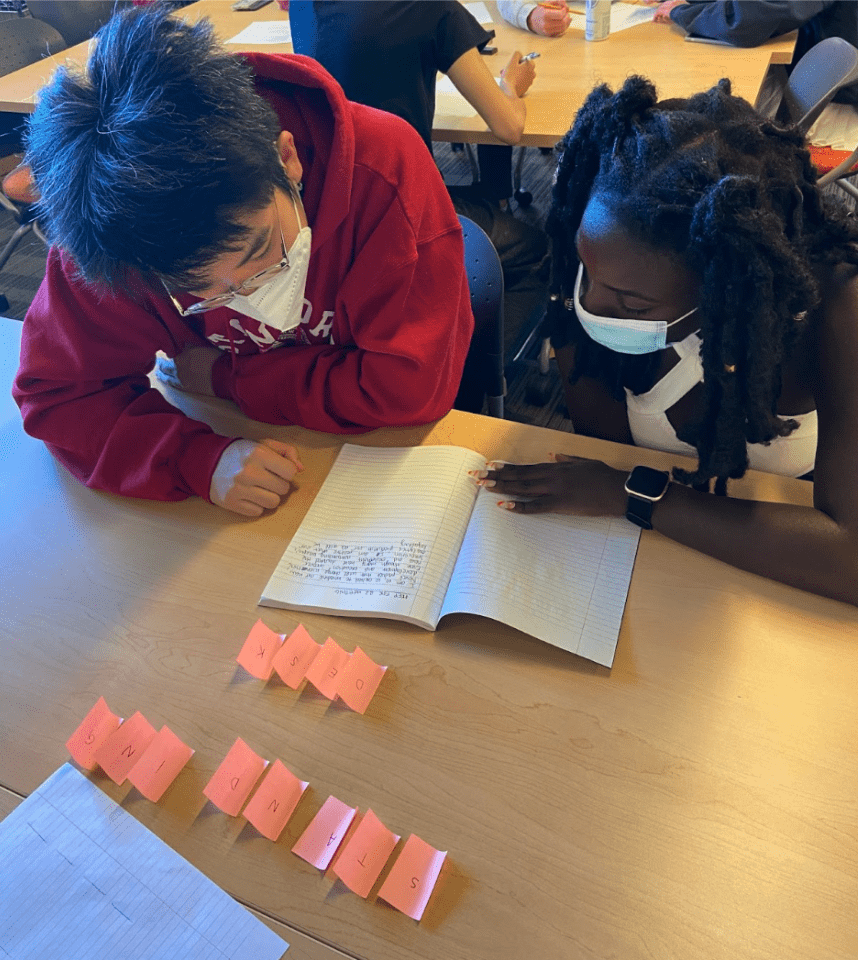

Throughout the course of the class, we had three distinct playtests. In the first one, we tested some puzzles in isolation, in the second, we developed the puzzles further and added some narrative and, for the last, we tested the full experience escape room in the actual location and with more refined puzzles and acting. All playtesters were also students in the class but they did not have any previous background on our game, which kept their experience as unbiased as could be. In our first playtest, we had two participants walk through the puzzle and quickly noticed that the ideal number of participants for our escape room would likely be two as it is enough to make sure every puzzle has more than one perspective and so that players can bounce ideas off each other. We believed that, since our puzzles are quite small and constantly interactive, any more than two participants would likely lead to players feeling crowded or not needed.

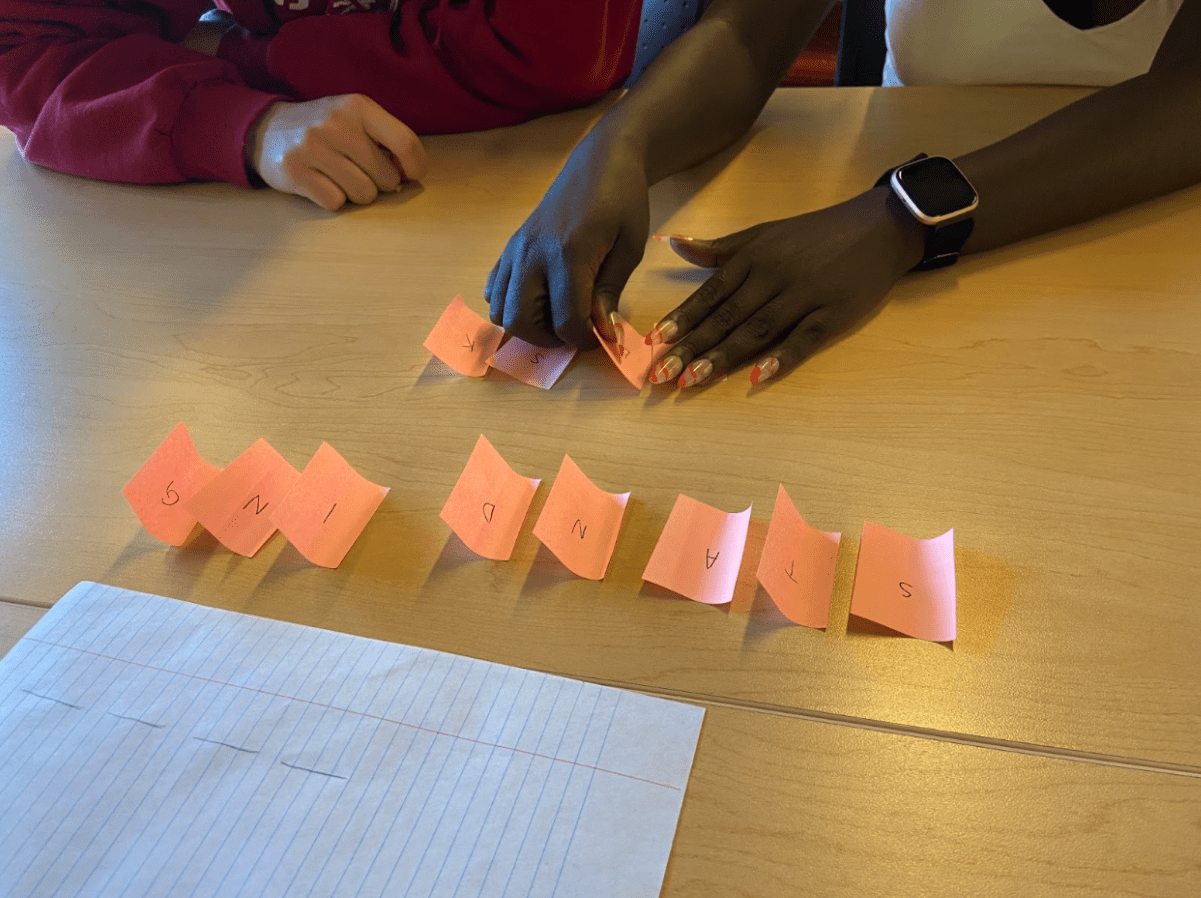

Image 1: First Playtest – two playtesters solving the notebook clue

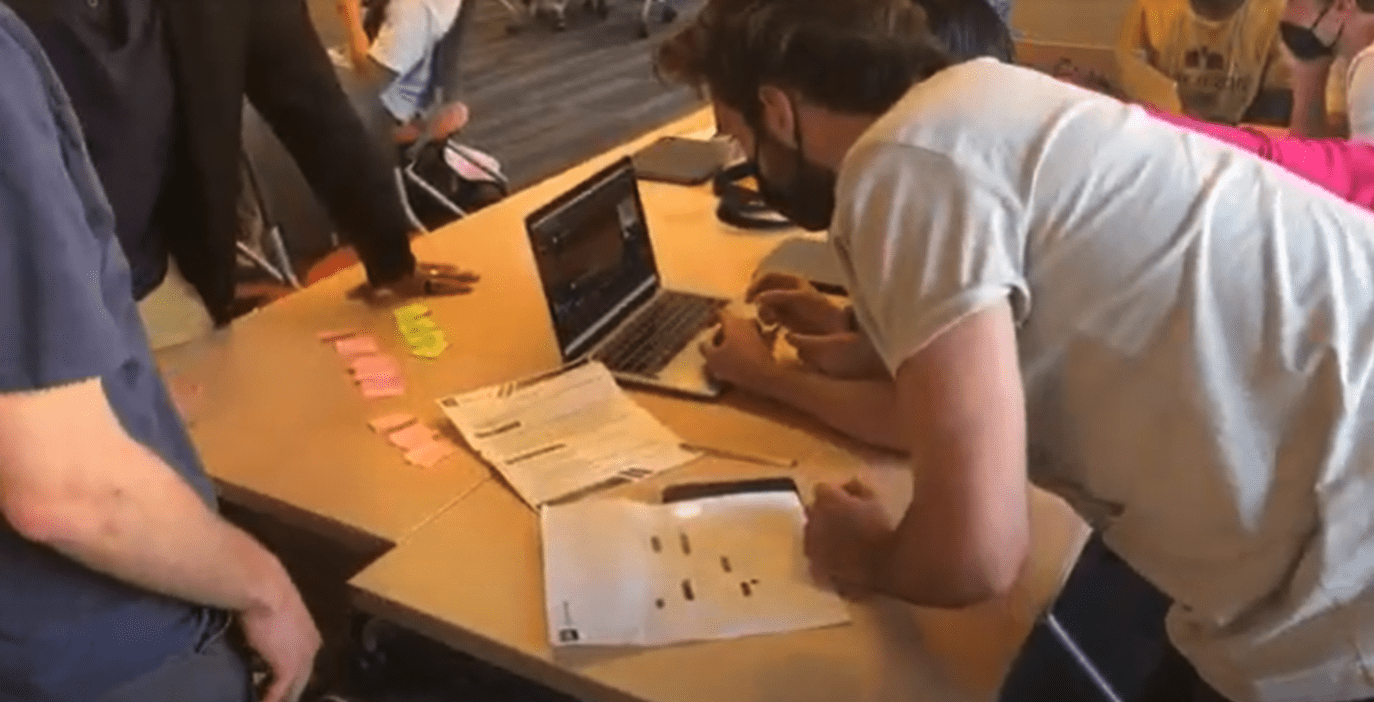

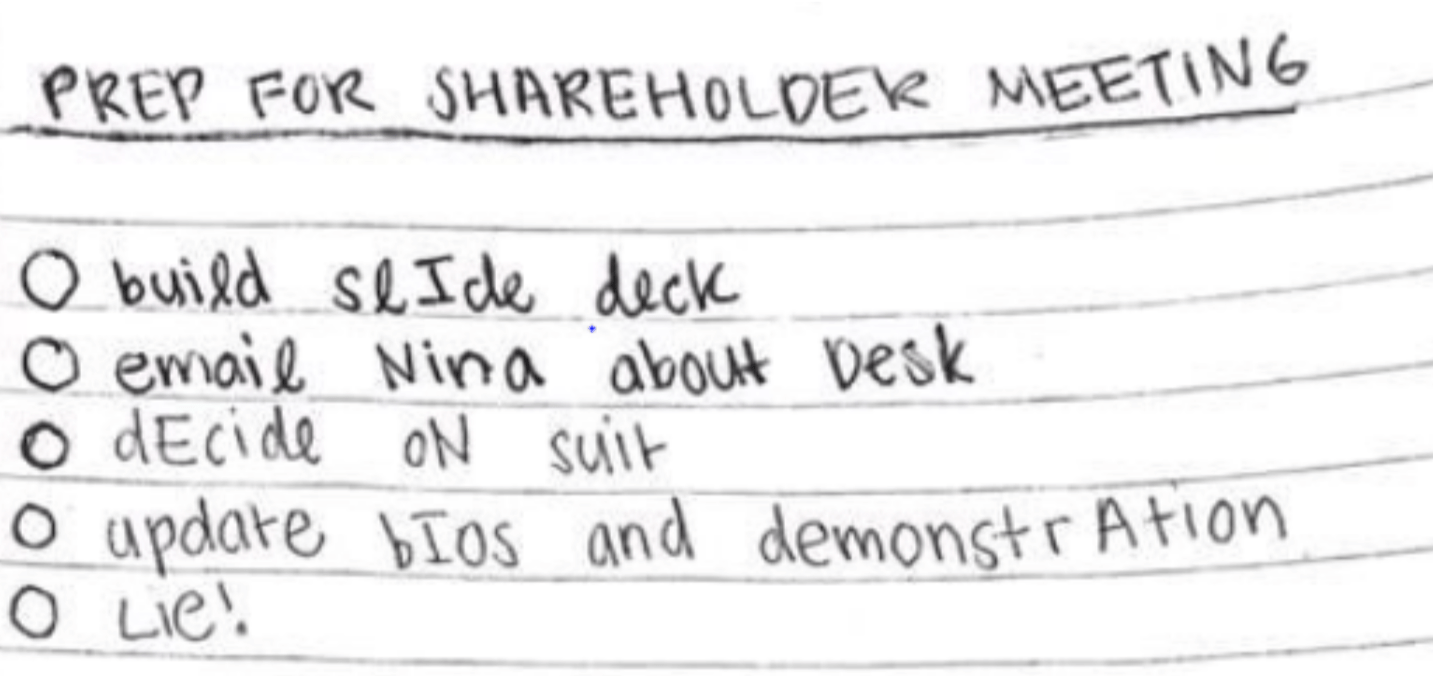

In our second playtest, we had four people, which was way too many. In fact, the group fragmented and did not work together. For example, a few of our puzzles involved a computer (navigating Slack and joining a Zoom call), when we had more than two people, they didn’t all fit on the Zoom call and couldn’t cohesively navigate the Slack. Below is an image from our second playtest where only two of the four participants can interact with the computer puzzle at a time.

Image 2: Second Playtest – only two out of four players interacting with computer

We got a lot of great feedback in our playtests, but we also struggled to make the playtest realistic representations of our escape room. In our first playtest, we were able to walk through all the puzzles we had prepared up until that point. With some help, the players were able to solve them all and we got positive affirmation from them. However, without the setting of the room and the narrative, it was hard for users to feel connected to the clues or understand how they lead into each other. That is why we often found playtesters asking questions like “what should I be looking for?” and not being able to jump on the clues right away.

That is why for the second playtest (still in the main classroom) we made sure to set the scene as best as we could and act out the starting narrative. Players had a clear sense of direction and were able to work within the woven narrative. Once they knew the overall direction, they could focus on solving the puzzles we had built and tweaked. However, as we weren’t in the correct setting with all our props and space, we struggled to create a feeling of exploration. In fact, one of our team members had to act as a coffee pot and a printer so users could “feel” as though they were interacting with an object.

The final playtest was the most successful and we were able to pull out all the stops. We were extremely pleased with the way the players utilized and explored the space. They were able to interact with all the props (printer, notebook, coffee pot, post-its, etc.) and slowly discover the story on their own. We enjoyed watching the players move through the room and think creatively about what the room could offer and how that would fit in the start-up, techie culture. Unfortunately, we did not set up enough roadblocks to prevent players from interacting with the puzzles in the wrong order. For example, they found the coffee pot before the standing desk clue but didn’t know what it meant yet. Although they were able to find the clues, we made sure they needed to piece the clues together in order so, towards the end, the players were organizing some clues they had already found.

Testing and Iteration History

For the first iteration, we focused mainly on the puzzles themselves and testing whether the difficulty level was appropriate, understanding how many players would be ideal for the puzzles, what type of interactions excited the users the most and discovering the main pain points that, as designers, we missed. We tested out an early iteration of: the notebook password, the slack channel, the meeting agenda, the anagram and the periodic table clue. As a general realization, we found that the puzzles themselves lacked intuitive direction. For example, if you see a notebook, it isn’t perfectly clear that somewhere in that notebook there is a hidden password for a computer. We also found the difficulty level of the anagram to be too high; the players didn’t know if they needed to find one word or more, especially considering the “obscene amount of consonants” in “STANDING DESK.” The Slack channel and the meeting agenda were home runs which is why they were barely modified going forward.

Image 3: First Playtest – players had to be told they were looking for object in room

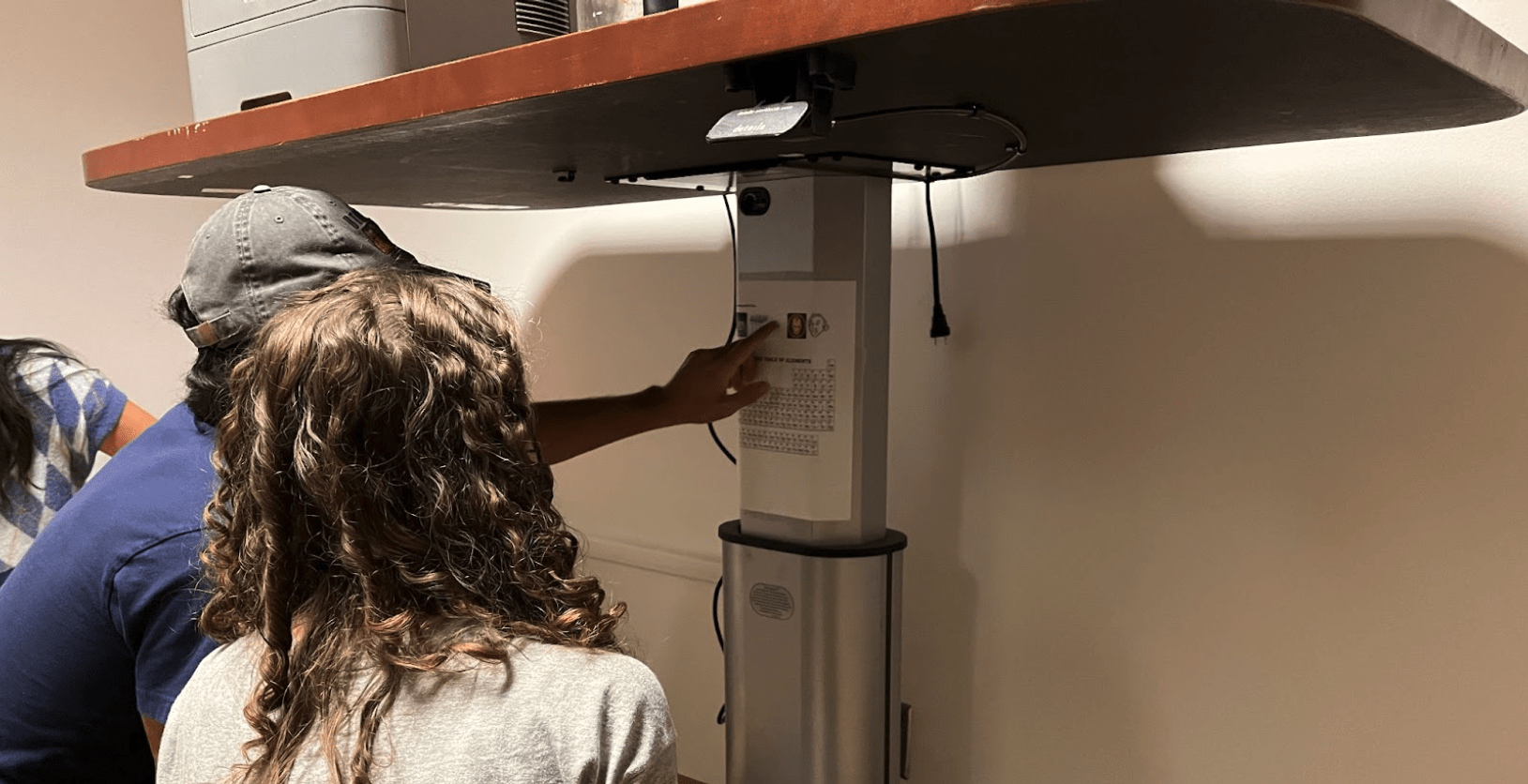

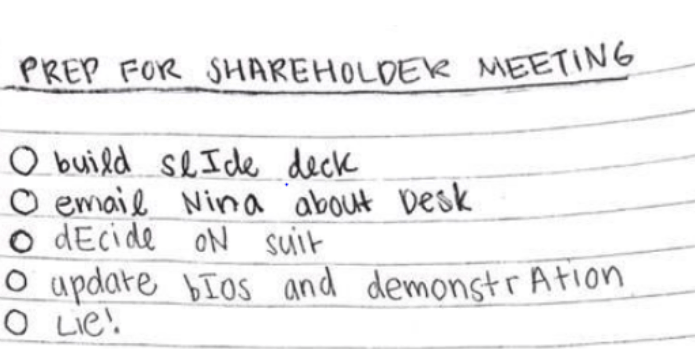

For the second playtest, our objective was to introduce some narrative elements, narrow into the appropriate difficulty range for the clues and have them feed into each other to convey our story. We created an introductory script, which we acted out, that would tell users where to start (the notebook password clue) and what they had to find (a location and a compound). This made it much easier for them to get started and follow a general directional thread. In our last playtest, we noticed players were obsessing over the imperfections in the notebook rather than looking at the first letter in each row as we wanted them to. After discussing with Laura, we decided to use this to our advantage and hide the clue in the imperfections by capitalizing certain characters to spell out the password, as shown in Image 4. We also added a post-it note saying “Note: IT says to keep all passwords to 8 characters” to hint that they should be looking for an 8 character long passcode. These changes made for a much better overall notebook clue. Additionally, we iterated on the anagram clue by using two different colored post-it notes to signal the two distinct sets of characters for each word. Players were quickly able to decipher “DESK” and had to work a little harder to get “STANDING” although it was not excessive.

Image 4: Hiding password “INDENIAL” in the capitalized letters

The third iteration was all about creating an immersive experience through the narrative, connecting the puzzles to augment the story and leveraging the space we were given. We refined our script and added dedicated character actors. One of our team members acted as the boss, Amy Goodwill, who gives the participants purpose and sets them in the game. Someone else acted as the CEO Dr. Don DiCepto, who barges in and introduces the conflict in the company and sets off the escape room.

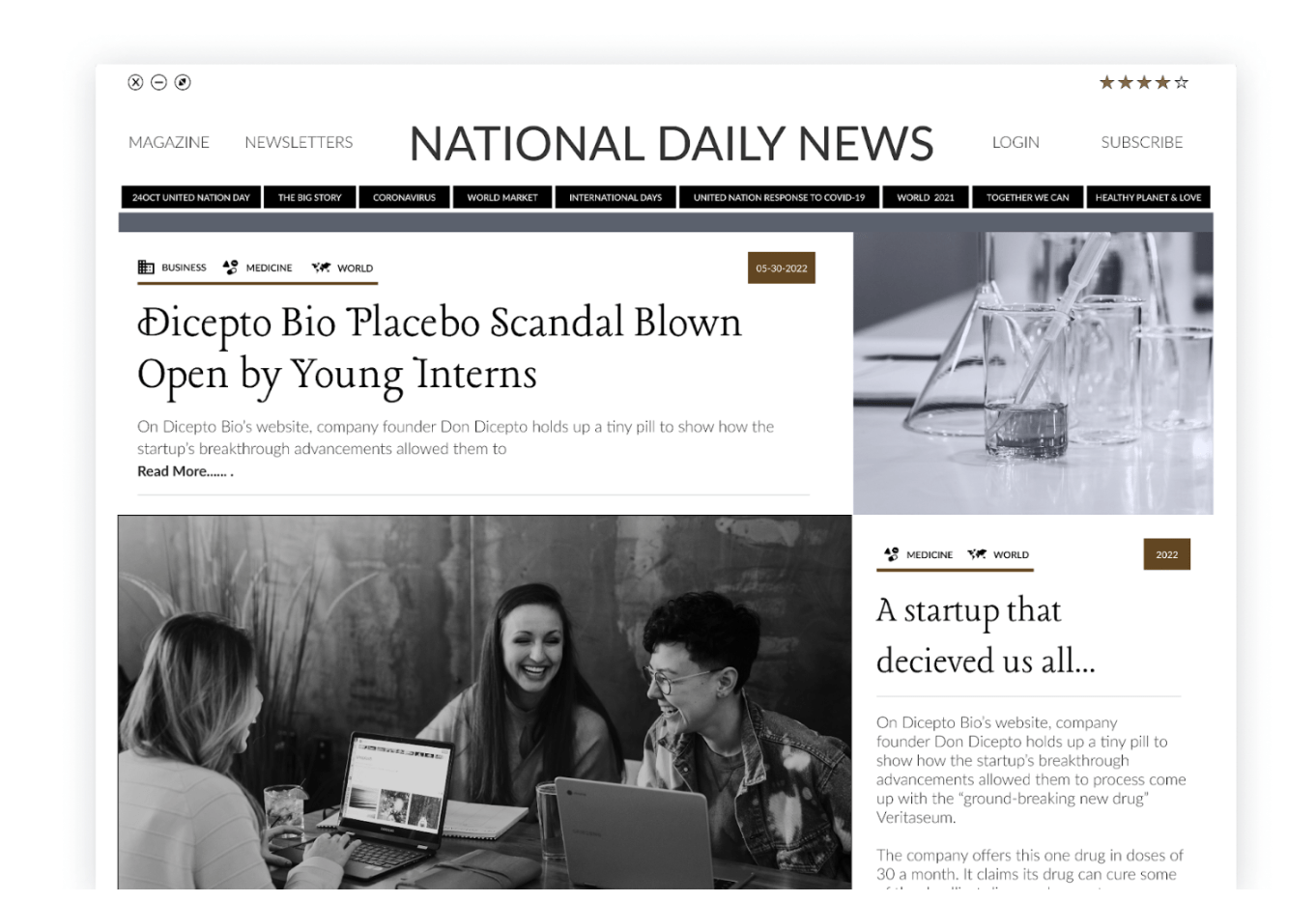

Finally, another team member played a NY Times reporter who interacts with the players live. In terms of the space, we wanted players to move around the room to find the clues. We placed the post-it anagram puzzle on a whiteboard on one wall, the computer puzzle on one end of the table, the notebook puzzle on the other end of the table, the standing desk clue underneath the desk and the coffee clue on top of the desk. We wanted to create the illusion that the players were rummaging through Amy’s office to find her hidden clues. Once again, we struggled to make the out-of-order clues impossible to find (the post-its are evident as soon as you walk in for example) but we made sure to provide a critical clue only at the right step to make the puzzles solvable. For example, you would only know to raise the standing desk once you solved the anagram puzzle as shown in Image 5.

Image 5: Discovering a clue hidden underneath the standing desk

We received valuable feedback from Christina, Eugene, and two of our classmates during our final playtests! Our findings and takeaways are summarized below:

- The final clue could be more complex. Players were surprised by the revelation that the secret compound was sugar and not something “spicier.” Playtesters tried to pry apart the sugar packet inside the coffee pot to unearth a different answer to the compound, and felt that this clue was a little anticlimactic. If we choose to stick with sugar as our final compound, we received feedback that the NYT reporter should underscore the use of a placebo. Another suggestion was expanding the puzzle to instead hide a clue to the final compound in the sugar packet, requiring users to again refer back to the periodic table to piece together the final compound.

- We could add more atmosphere. From both class and this playtest, we realized that we could play music in the room to create more of an atmosphere to the room—it would have been eerie to play a generic corporate playlist, or use a playlist from Checkpoint 1—and add posters advertising Decepto Bio to fully immerse players in the Dicepto Bio environment. Both these choices would customize the space further and emphasize the tone of the room. The posters offer the opportunity to provide further hints that could potentially tie into the chemical compound puzzle, but we would have to be careful to not make the posters red herrings.

- Players wanted more gratification. We learned that playtesters wanted more value and pressure assigned to win and fail cases in the room. If we had more time, we would add a “fail” scene to our script, and also design certificates with player names in the case that they win.

Image 6: Mockup of finalaper article to give players upon success

- The notebook clue was so easy that it was tricky. As seen in the video above, playtesters were distrustful of the notebook clue and thought that there was hidden meaning beyond the single page with the clue. To draw more attention to the notebook, we would remove the red herring books that we placed on the table along with the notebook. A possible future direction could be exploiting player interest in dents left from previous writing and encouraging players to color over engravings to find the laptop password. This would also make the clue more engaging.

Game

Printable Clues

A link to a PDF with all of our clues that are printable is available here.

In addition to the clues contained in the PDF (more information also provided in the Game Walkthrough section), we had the following clues:

- A coffee pot with a sugar packet taped to the bottom. Players are led to the coffee pot from the periodic table clue and must pour out the coffee in the coffee pot to see the sugar at the bottom and piece together the final clue (that sugar is the secret ingredient, and Decepto Bio is making placebos).

- A Zoom link available on the computer after unlocking that allows players to interface with the NYT reporter. The reporter (played by an actor) instructs the players to look at the printer in the room for more clues, and gives context for the escape room, as well as the information players need to provide to escape.

Demonstration of Experience

Game Walkthrough

Image 8: Initial brainstorming board to identify main puzzles and how they fit together

You walk into a conference room. A woman is standing there. She welcomes you in: “As you know, you’re some of my top performing employees here at Dicepto Bio. With the upcoming launch of our new product tomorrow morning, I wanted to gather you here for something very important —”. Before she can finish speaking, there is a knock at the conference room door. A man opens the door and demands that the woman leave the room: “Amy, get over here!” Amy apologizes to you: “Sorry, our CEO needs to check in with me about something. I’ll be back.” They both leave the room, and you hear the door lock shut.

Puzzle 1: Notebook

There is an open laptop sitting on the table with a post-it note reminding you that “IT says to keep your passwords to 8 letters!” This prompts players to look for a clue to the laptop’s password. There is a notebook sitting next to the laptop on the conference table. When opened, there is a single page of writing that outlines a fake checklist. Players will notice that some letters are wrongly capitalized. These capitalized letters spell out INDENIAL, which is the password for the computer. Once players decode this clue they will unlock the laptop.

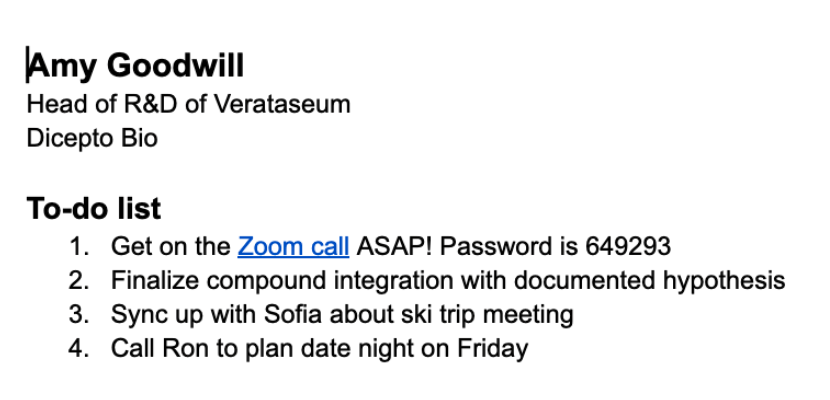

Puzzle 2: Zoom call

After unlocking the laptop, players will immediately see a Google doc with Amy’s to-do list in it. The first item in the list is to join a linked Zoom call ASAP. Players will click the link and join the Zoom call, where a New York Times Reporter will be waiting for them. He will be confused to see someone other than Amy on the call: “Amy? Wait…you’re not Amy. Well, whoever you are, I’m going to need your help. There’s something suspect unraveling at Diceptio. It’s related to your star product. We need to figure out what’s going on before the company launches the product tomorrow morning — or a lot of liars will make a lot of money, and a lot of people could be hurt. Here’s what I need from you: the name of the active compound in the product, and its place of manufacturing. That’s what I need to finish the report. I’d suggest you check Slack first. Hurry! We can’t let them get away with this!” This prompts players to check Slack on the computer.

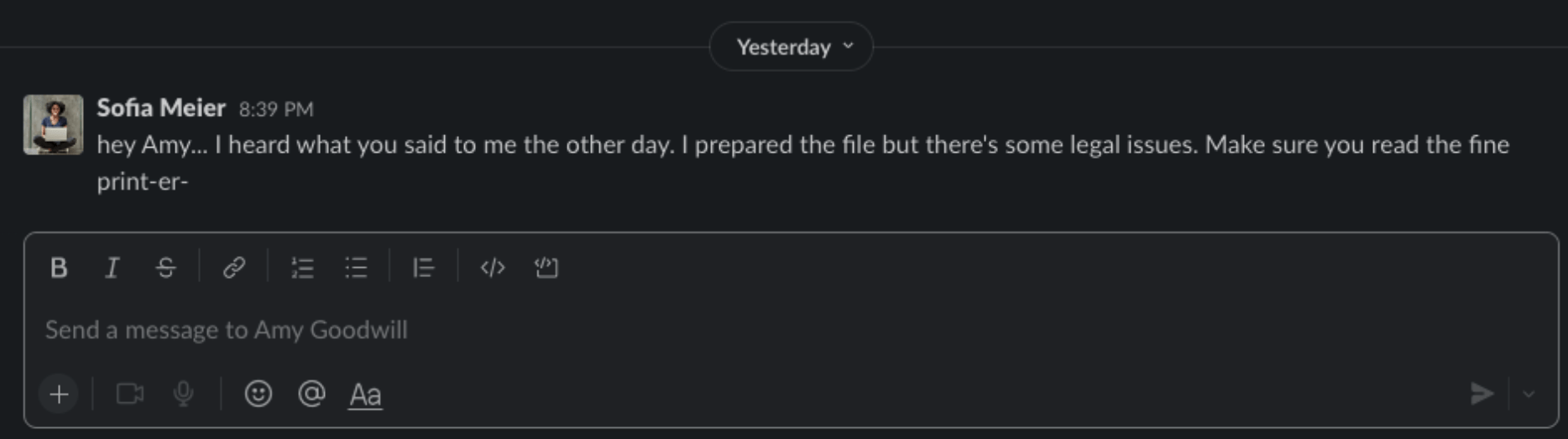

Puzzle 3: Slack

On Slack, players will see toxic corporate messaging from the company’s CEO in the #general channel and then receive a DM from someone named Sofia that includes the phrase “print-er-”. This is supposed to mimic someone hesitating in a sentence while also cluing players in to check the printer. In an ideal version of our game, players would then see the open printer application on the computer and open it. There, they’d find a paused printing job. They could unpause it to print out the next clue. In our final playtest, the printer was malfunctioning, so we simply left the document on the printer. This also worked as players were clued in to check the printer and found the printed document.

Puzzle 4: Agenda Swiss Cheese

The printed document is a piece of paper with black ovals scattered across the page. Players will notice that this paper has the same header as the many company agendas that are laid out across the conference table (as if in preparation for a meeting). When placed behind the agenda, the black ovals line up with certain words: watch, neutrality, Roger Federer, Credit Suisse, chocolate, Matterhorn, ski. Since players know they are looking for a geographic location, this clues them in that the location is Switzerland. They have completed the first path of clue-hunting.

Puzzle 5: Invisible Anagram

Now, players have to figure out the name of the compound in the product. They’ll notice three colors of blank sticky notes clustered on the whiteboard. Below the sticky notes, there are an array of strange-looking markers. If they pick up the markers, they’ll realize they are actually invisible ink pens with lights on the end. Flashing the light on the sticky notes will reveal that some have letters written on them. The blue notes have nothing written on them, and the pink and yellow notes each have letters. They’ll realize that the pink letters make up one word and the yellow letters make up another word. They’ll unscramble the anagram through trial-and-error to find the word “Standing Desk.” There is a standing desk on the other end of the room, where they’ll head next.

Puzzle 6: Standing Desk

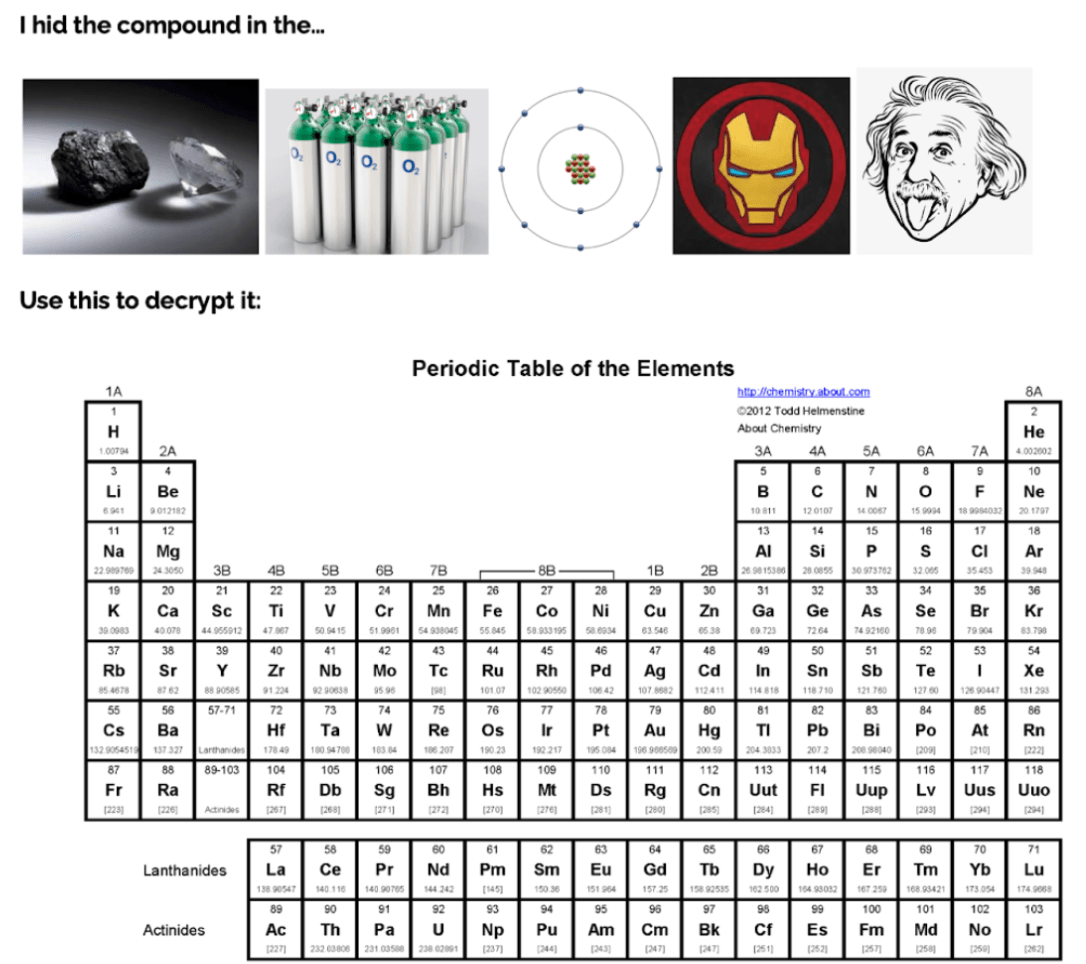

At the standing desk, players will use the button to elevate the desk and reveal a periodic table taped to the hidden part of the desk stand. Above the periodic table there are 5 pictures prompted by the statement “I hid the compound in the…” This should tell the players that solving this clue will provide information about the chemical compound that they need to bust Dicepto Bio. They will eventually recognize that the pictures are hints to elements on the periodic table: Carbon, Oxygen, Fluorine, Iron and Einsteinium. Pairing these elements to the relevant letters on the periodic table, the clues should spell out COFFeEs ( or COFFeE if they interpret Einsteinium as “E”). This will lead the players to the coffee maker on top of the standing desk that contains a coffee pot full of coffee.

Puzzle 7: Coffee Pot

As the last step of the escape room, players must find the chemical compound in the coffee pot. Within the coffee, there are packets of sugar taped to the inside of the coffee pot. Beside the coffee maker, there are a few empty mugs. In order to find the clue, they can pour out the coffee into the mugs to reveal the sugar packets at the bottom. Otherwise, if players are feeling bold, they can also reach their hand into the full coffee pot and fish around for clues. From the sugar packets, they will realize that the chemical compound is Sugar (or Sucrose)! They now have all the information that the New York Times Reporter asked for. They log back into the zoom and type in “Switzerland” and “Sugar” into the Zoom Chat. This triggers the New York Times Reporter to turn their Zoom video back on and begin speaking. “This is amazing, thank you so much for figuring all of this out” they say. “I can’t believe that Veritaseum is just a sugar pill, the company is selling placebos! We can now finally put Dicepto Bio to rest. You’ve succeeded!” With those last words, the door unlocks and the escape room has successfully ended.

Final Playtest Feedback (for other games)

Final playtest feedback from Alejo who playtested soRRRt

This was a very interesting single player video game themed around sustainability and dorm culture. For this game, the player competed against the system to complete tasks and learn about recycling. The game was set in a college dorm where you (the student) have a very dirty room and there is a dorm proctor about to come by and check that your room is clean. There are 8 different types of trash lying around and 4 different bins where you need to place the trash, depending on what type of trash you are dealing with. The designers were very effective at creating a sense of urgency with the time pressure, the environment and the audio.

In my eyes, there were two different main types of fun present in the game: Narrative and Challenge. There is a narrative element around you being a student collecting trash in your room and being immersed in this college environment. In terms of challenge, picking up the trash and sorting it correctly is not the easiest thing to do. One aspect of the theme and game that made it very enjoyable to play was the feeling of fulfillment I got every time I was able to recycle all the trash correctly. You feel like you helped make the world a more sustainable place.

The mechanics of the game were extremely simple. You are only allowed to move around, pick up trash and place it in the right bin. That made for a super simple onboarding experience and a very easy learning curve. However, I do think there is room for improvement in the onboarding process. The designers had a large paragraph of text explaining the game and the mechanics and I would have probably preferred a more interactive learning experience (maybe just picking up one piece of trash and sorting it correctly). I think the mechanics could still be polished a little more as there were a few implementation bugs when collecting the trash and moving it around (things would often magically disappear), but I do understand this was just a small playtest experience.

Finally, the objectives, outcomes and results of the game are quite straightforward. Your objective is to clean up the room and the only possible outcomes are success or failure. I know they discussed the possibility of rating your ability to clean the room based on how fast you completed your tasks but that was not yet implemented.

Final playtest feedback from Anooshree who playtested Minecraft Game

This game was a really innovative take on an escape room! I thought the designers’ choice to use Minecraft as a medium allowed them to 1) explore narratives that would be infeasible or too ambitious for the space provided in Durand and 2) equip users with unique skills normally only found in coded games.

As someone who has never played Minecraft before, I did think that this game was a little intimidating to play, and the initial starting room only contained minimal instructions that didn’t provide information necessary to complete some of the initial clues. Furthermore, the game was incredibly expansive, but sometimes the different sections (the prison tunnel and hidden farm, for example) didn’t dovetail together smoothly. As a result, it occasionally felt like the game just dragged on, but I imagine experienced Minecraft players would progress through the stages faster than I did. Finally, it sometimes felt a little useless to have another player present in the world because some of the tasks were highly individualistic.

I definitely noticed a lot of different types of fun in this game! The presence of Fantasy, Narrative, Challenge, and Exploration were especially distinct. Furthermore, the embedded and emergent narratives worked together well; the initial context of escaping from a prison was a good base for the more fantastical elements of trading diamonds and jumping into a lava pit. Overall, I think I would enjoy this game more if the narrative was more cohesive and the controls were easier to understand (or if there were explanatory “levels” as in PvZ), but the designers did a fantastic job!

Final playtest feedback from Kevin who playtested Perfect Partner

Perfect Partner is an interactive storytelling game that takes place in a house. It is played on the computer. The husband of the protagonist cheats on her, prompting her to see an ad for a robotic husband, a “perfect partner”. The narrative evokes themes around the difficulty of marriages, the rise of artificial intelligence, and personal agency. The setting of the house was dark and haunted, giving an eerie mood to the whole story.

The game creates a compelling emergent narrative from the setting. The opening scene shows a photo album of photos from the couple’s marriage and kids, giving a sense of the gravity of the relationship lost to infidelity. The protagonist wakes up in a dark room with her husband’s phone on the bed. The player has to search for the passcode to the phone, creating a sense of tension and anxiety that evokes what the protagonist must be feeling. The gameplay alternates between storytelling and puzzle solving. As a result, the types of fun I encountered were sensation and narrative.

I found the game to not be challenging enough. The puzzles, which were the primary form of interaction, were generally simple (i.e. find an object in the house). A richer set of puzzles could make the game more interesting, although the game was unfinished at this point. The conflict in the game seemed to revolve around the protagonist, the cheating husband, and the robotic “perfect partner”. The outcome is the choice of the protagonist about her life, which the player helps in deciding.

Final playtest feedback from Morgan who playtested Ma Nasa

It was really cool to play another game that was a physical escape room like ours, however it is interesting to note that until they told me, I was unaware that this game was supposed to exist in a physical room. During my playtest, we only tested one of their puzzles – decoding a message in alien symbolic language. One strength of this puzzle was its digital component. It was nice to have a digital program that automatically oriented us in the story and kept track of the time that had passed. I also think it was effective to have scaled hints that got increasingly more helpful but only unlocked after a certain amount of time had passed. It allowed the puzzle to have a forced linearity where players could not jump around in the game or access other puzzles or hints unless the game designer allowed it.

My main takeaway from this puzzle was that it was very challenging and complex. My playtesting group required all four clues to be unlocked before we finally solved the puzzle. The puzzle asked us to decode three lines of alien instructions using many (I estimate over 25) lines of English- alien language translation. I think that the large amount of translated lines made the puzzle more confusing. Especially because the alien language was symbolic where different symbols could be combined to have entirely different English meanings. This made trying to decode the alien symbols more difficult since we had so many examples of each alien symbol translating to a different English word. I also found some of the clues more confusing than helpful. Perhaps this was an indication that I need to brush up on my English grammar, but one of the clues used parts of speech (subject, verb, object, etc.) to provide information on the structure of the alien language but I found it confusing since some of the phrases were compound sentences. It was hard to know when this structure applied and when it didn’t. I think my biggest critique, however, was that there was no way to confirm that you had correctly decoded the puzzle. The game designers had to tell us that we had solved the puzzle, Without that intervention, our team would have kept trying to decode. I think this could easily be solved by extending the digital component – perhaps users have to submit the phrase digitally to confirm or deny whether they decoded it correctly.

Overall this puzzle took us about 30 minutes to complete, and the entire escape room is supposed to take 45 minutes. I tend to think that is a long time to spend on one puzzle in a physical escape room. Calling back to my earlier statement, I don’t think this game needs to be a physical escape room. When I think of physical escape rooms I think of puzzles that are highly integrated into the physical space. This game, in contrast, consists mainly of two puzzles, both of which don’t require a lot of interaction with the surrounding environment. Specifically since the largest most time consuming puzzle is purely digital, I think this game could work better as an escape room in a box. In an escape room in a box, it would feel more natural that players would solve the puzzles from a more stationary position, as this game requires. I think in a physical escape room, these puzzles could feel a bit more unsatisfying since players might enter the game expecting more physical interaction with the environment. Overall, I want to commend this group for their creativity and ability to create a truly challenging puzzle. They did a good job of creating an alien atmosphere with their digital graphic design and use of language.

Final playtest feedback from Tara who playtested Ma Nasa

I thought that this game had an interesting premise and great visuals! The idea of escaping a room on an alien planet is easy to understand, and the graphics on the team’s self-designed website and clues matched the original premise. I playtested the blue that involved translating a command using an existing translation of a different text.

While the clue was satisfying to solve–and I really enjoyed the hints on the website that unlocked with time—I thought it was a bit counterintuitive for a physical escape room to center around a single clue that involved everyone sitting down in one place. It didn’t really utilize the space we were given in Durand, and it didn’t allow each player in the escape room to individually search the room for clues. Furthermore, the hint itself used an existing hieroglyphic language that had pretty complex word constructions, and I don’t think any of us playtesting could have solved it on our own.

After we translated the clue (which did involve some aspects of Narrative, Fantasy, and Challenge), we were told that there was only one more physical clue required to escape the room. I would have loved to see more embedded narrative elements that involved searching the room for other objects and clues that would tell us about this alien civilization. I think the team did a fantastic job, but think there are a lot of directions for future work.