Game Name: Journey

Creators: Jenova Chen, Nicholas Clark, Bryan Singh, Robin Hunicke, Chris Bell

Target Audience: This game is aimed at individuals seeking a calm, fulfilling experience. It’s suitable for players aged 12+, but its aesthetics and subtle story would probably be best suited for anyone over the age of 16. Due to the simple controls, it caters to a wide audience irrespective of skill level.

Types of Fun: The game facilitates fun through discovery and narrative (more on this later).

Core Mechanics:

- Procedures:

- Rules: The rules all happen behind the scenes in this game

- Outcomes: The explicit outcome in this game is invariable: the player reaches the peak of the mountain and restores life to the previously frozen and decaying world that the player had journeyed through to get there. In a more abstract sense, most players I imagine would be left with a sense of awe, wonderment, fulfillment, and an appreciation for the beautiful experience they just played through.

- Resources: The only expendable resource in this game is the scarf material: it’s what allows the player to fly in short bursts and can be destroyed by the game’s only hostile creature.

- Boundaries: While the game’s explorable area is vast, one can reach the edges of the map, at which point a gust of wind gently guides you back toward the playing area.

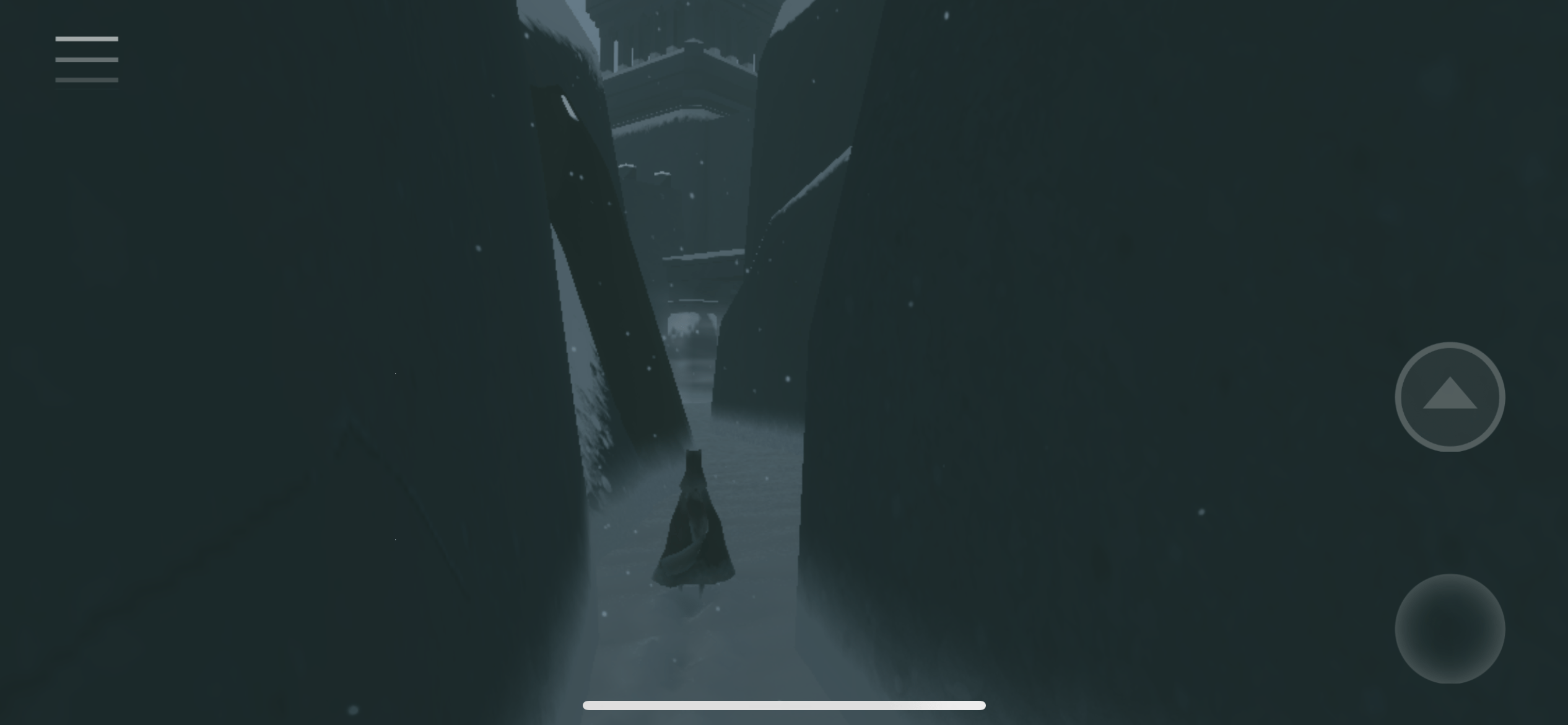

How walking tells the story: The physical experience of walking in this game is the only way in which the story unfolds and for the player to unravel the narrative’s mystery. While the exploration of space of course plays a big role in this, the actual experience of movement in this game itself tells a story. When movement is labored—such as atop windy sand dunes or while traveling through the frigid snow—the player knows that the environment is hostile and that something is wrong. On the other hand, when the player is moving or flying freely, they know that all is right with the world, that this is how the world is meant to be. In this way, the juxtaposition between labored and free movement tells the player how they’re meant to be feeling and helps them understand how the space they’re in relates to the game’s overarching narrative.

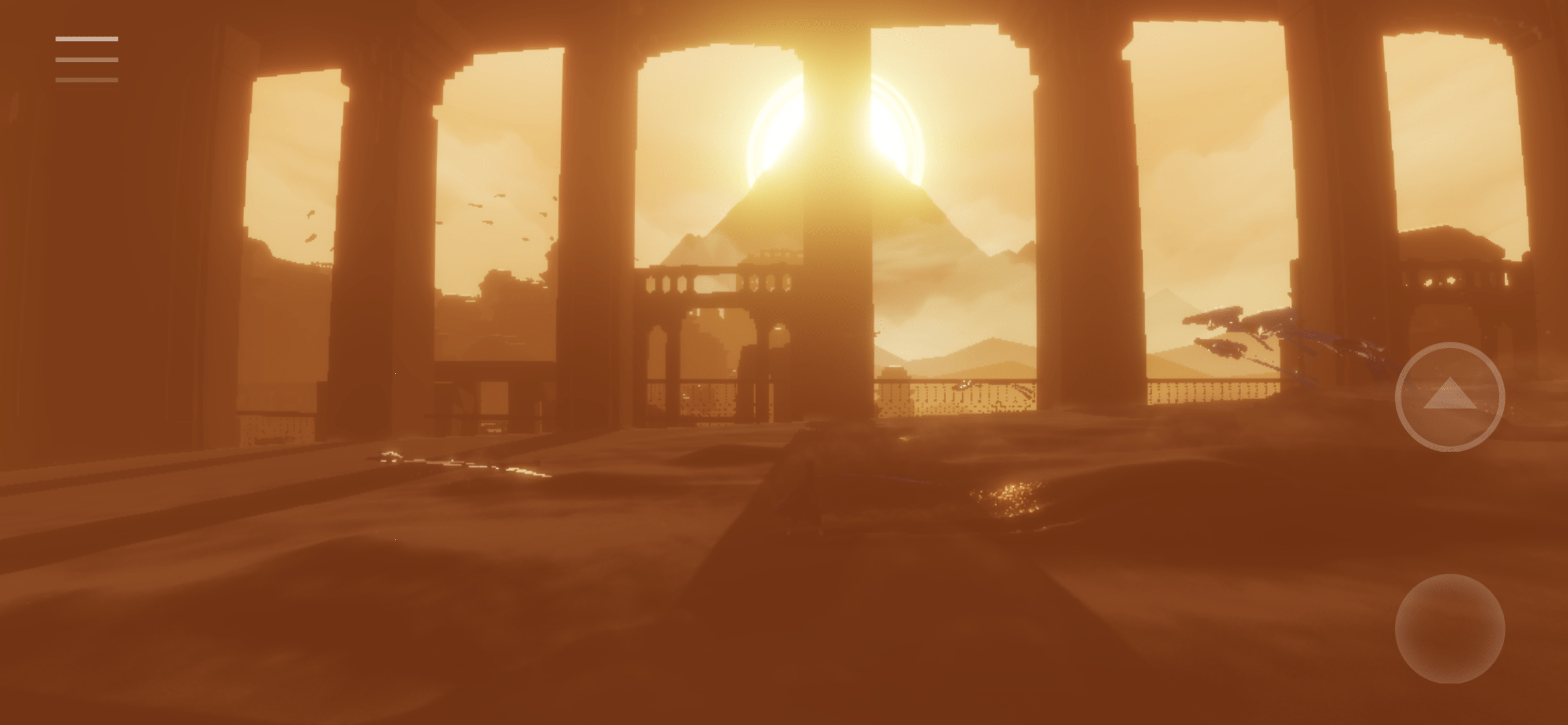

In a more typical fashion, however, walking is also the only means of unearthing embedded micronarratives, whether that’s finding a painting beneath a waterfall of sand or walking down a corridor with the crumbled remains of once beautiful buildings. As the player walks around the world, they can begin to piece together how it used to be and what’s led to its ruin.

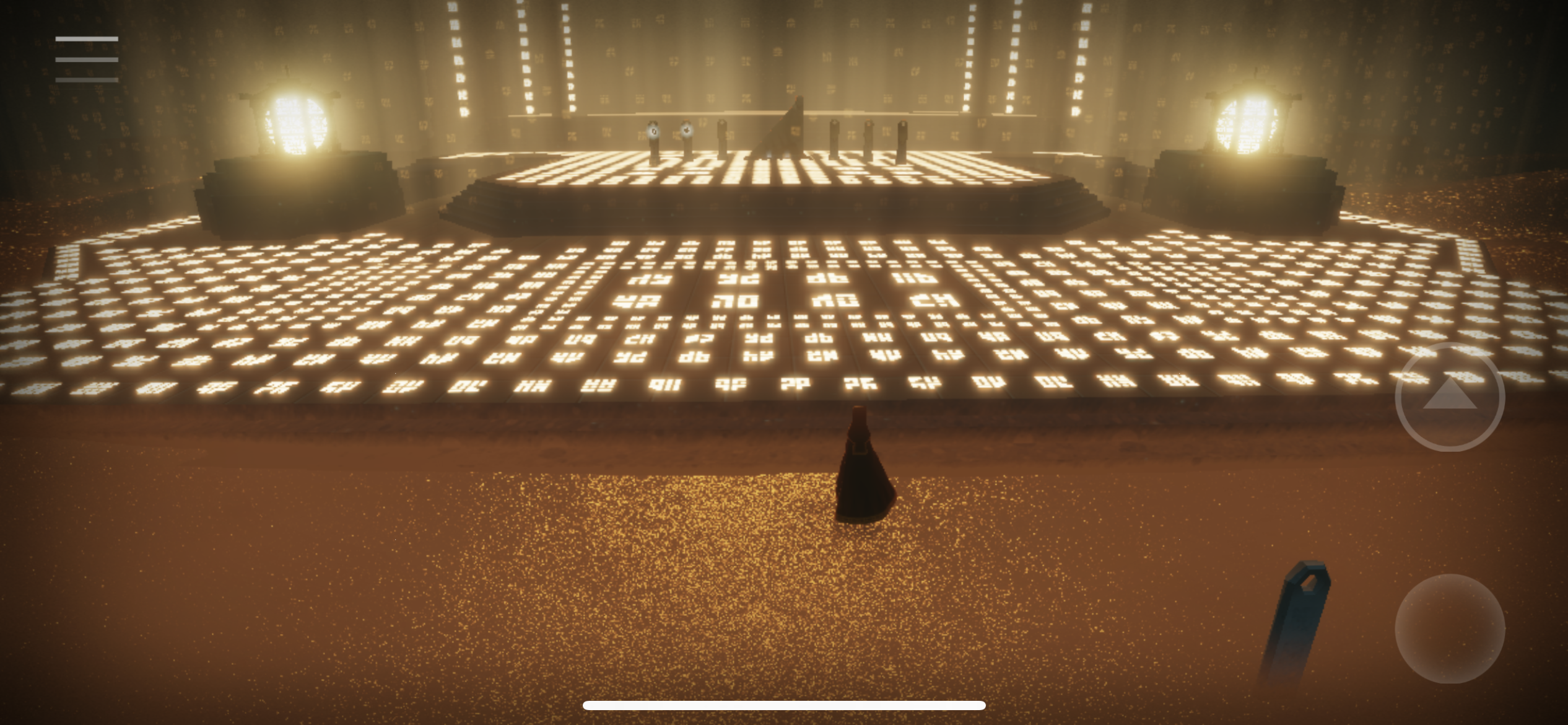

Further, the fact that getting from area to area is sometimes difficult leads the player to better appreciate each piece of the story they stumble upon. If it was easy to skip from location to location, each one wouldn’t feel as special. That it took an arduous journey to get to each place gives the player more incentive to really drink in whatever they find. Even simple inscriptions become something to marvel at.

Lastly, this game epitomizes the cliche that the journey is more important than the destination. I never thought I’d quote Miley Cyrus in my coursework, but, truly: “It’s not about what’s waiting on the other side, it’s the climb.” The sheer amount of time spent walking and struggling against the elements is what makes the story so satisfying. It gives the player the feeling that they’ve endeavored to unlock the mysteries of the world.