Designed by Alex Hurtado, Fernanda Kramer, and Ciera Okere

Summary and Artists Statement

Dearest player, welcome to high society: where gossip is the main currency and a dinner invitation is a coveted prize. Two exclusive parties are coming up, and the hosts are eager to brag about which A-listers they managed to snag for their extravagant night of good eating and lofty conversation. For the newly-famous like yourself, knowing who’s on the list is a powerful thing, but it is difficult knowledge to come by. As you step into the ranks of the A-list celebs, remember only one thing: name dropping is tacky and a minor faux-pas can have you blacklisted for the event season.

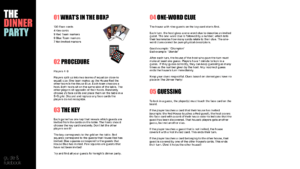

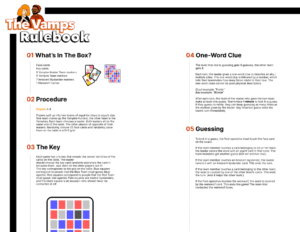

This is the premise of The Dinner Party, an association guessing game. Born from the age-old question “If you could have a dinner party with 8 people living or dead, who would you invite?” and a fascination with social dynamics in celebrity circles, the game is a mix of Codenames and Guess Who. It is intended to engage the players in a fun night of pop-culture trivia, against a backdrop of gossiping and secrecy. Designed for 4+ players, this game is designed to be played by friend groups at game nights and spark rousing conversation, particularly for players ages 16-28.

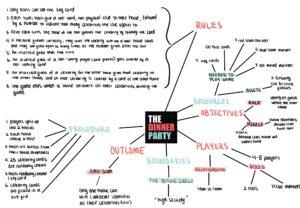

Concept Map

Initial Decisions, Playtesting and Iterations

We went through several rounds of playtesting and iteration to develop our final game. Each playtest was conducted with between 4 and 6 players selected from our game design class. After each playtest, we elicited feedback from our players and incorporated their reactions with our own observations to create another iteration of our game.

Going into our first playtest, we had a loose idea of what our game was. Mechanically, we knew we wanted to do a mash-up of Codenames and Guess Who. We figured that we would keep the main mechanics of Codenames but now with clues that rely on visual associations. As for branding, we called the game Vamps, and it featured a diverse set of colorful pop-illustrated people as our face cards.

In our first playtest, we wanted to test two qualities: the viability of the game concept itself, and an understanding of the rules and procedures. The first quality answers the question “Is this game even fun?” while the second aims to ask “What doesn’t make sense? What can be clarified?”. We wanted to test the waters with our caveat on hints: the spymaster cannot give hints of physical descriptors. This playtest was also our first opportunity to try out the game as players rather than creators. Overall, the playtest went well! Players managed to pick up the mechanics of the game without much of a hitch — even those who were previously unfamiliar with Codenames. We played the game to completion with lots of chuckles and not much hassle.

Still, there were things to improve on. Thematically, our branding was a little confused — players questioned what our Corporate Memphis-esque illustrated people had to do with vampires and werewolves, and how vampires and werewolves motivated the mechanics of the game. Mechanically, our players had issues toeing the line of our “no physical descriptors” constraint. How could they avoid physical descriptors when everything they knew about our characters was just what they could see visually? Would hinting at a character’s style of facial hair count? What about the design of their t-shirt?

We found that both concerns were valid, and so made changes for our next iteration. We decided to brand our game under the more fitting — if generic — title of “Secret Teams” and aimed to clarify our hint constraint on what counts as a “physical descriptor”. We also aimed to add more visual personality to our characters (e.g., different poses, smiles, noses, features) so that players could latch onto more facets to build a descriptive hint.

Our second playtest intended to evaluate our thematic pivot and identify any lingering issues with our game mechanics. This playtest revealed a much more problematic issue with our game’s concept than any of us expected. Our players had a similar issue toeing the line around “no physical descriptors” while also trying to link multiple characters together. The spymasters went a few turns back-and-forth calling out single characters before one of them called out “software engineer, for two”. At once, the guessing player pointed out that — based on stereotypes — they could narrow down the field of characters to two male-presenting figures with glasses. This obviated the major problem of our game concept — that since the players knew nothing of the characters in question and could not use physical descriptors, most hints had to rely predominantly on stereotypes and the biases baked into them.

Immediately, we recognized this as an issue that must be addressed to progress in any meaningful way. This issue was cause for concern in the feedback we got from our TA, as well. We dived into a brainstorm of how we might design stereotypes out of our game and decided to shift away from our colorful illustrations of nameless characters and focus our game on notable figures of past and present. We figured that our players would be able to use their knowledge of each figure’s public background to construct more meaningful hints and would not have to rely on stereotypes or physical descriptors to get their points across.

Our shift to use notable figures also afforded us a great theme for our game. We decided to brand ourselves as The Dinner Party, a riff on the age-old question “if you can invite any set of people to your own personal dinner party, living or dead, who would you invite?” We printed out our dinner party themed rule sheet, character cards, and team markers in preparation for our next playtest.

For our third playtest, we wanted to test out our new shift. We wanted to know: how well does our game work relying on a pool of celebrities instead of nameless characters? To start, our playtest did not seem promising. At first, one of the players remarked “I only know a third of the celebrities, so I should not be our team’s host”. At another point, a different player asked if they could google one of the celebrities so they could figure out what they’re known for. On several different occasions, the hosts gave hints that referenced certain celebrities that the guessing players did not understand as a reference to anything. These observations pointed to a main issue with using a set of notable figures for our face cards: very few players recognized all the celebrities in play, and each player had a different set of knowledge and context on these figures.

The Final Iteration

To be sure, this issue was not catastrophic — the players were still able to complete the game and had fun doing so — but it definitely seemed like a valid pain point that should be addressed. We considered a few different solutions to this concern. One of the notable solutions included collating a cheat-sheet that enumerated each public figure and their notable achievements and distributing those pamphlets to the players. While we believe this solution would appropriately address the issue at hand, we did not have the time and resources to properly explore this route. Instead, we opted to make two smaller changes at the level of mechanical play and visual description. First, we added icons to each face card to indicate the field of celebrity each figure is known for (e.g., art, entertainment, history, etc.). We hope that this would give more context to our players without great knowledge of each figure. Second, we added a procedure to the rule sheet that allows all players to replace figures they do not recognize with a random figure from the remaining deck at set up. This should ensure that each team is working with a set of celebrities that they recognize and can riff on.

Finally, we iterated on feedback from our TA on avoiding ludonarrative dissonance. At the time of feedback, we had a solid theme and solid mechanics, but very little to connect them two in a way that was coherent. As a result, we worked on adding narrative to our marketing material that illustrates WHY the mechanics fit with the theme of The Dinner Party. In particular, we described how hoity-toity hosts would love to brag about their illustrious guests but also want to avoid the faux pas of name-dropping. Hence, they attempt to hint at their guests using allusion and roundabout descriptors.

A little postscript on the things that went unmentioned in the evolution of our game throughout the design process. First, note that throughout the process of playtesting, we played around with different physical constructions for our game cards — we experimented with size, with orientation of display, with fonts and readability, and even considered co-opting a Lazy Susan to serve as our game board. We also had to make decisions that went against the direct suggestions of our playtesters. On a few occasions our playtesters suggested that we scale the length of hints proportionally to the number of people being hinted at. While we agree that this would make the challenge of spanning a set of people with a single hint, we feared that such an addition would make the challenge too easy. We imagined that a host could exploit the rule by giving full sentence hints if they wanted to. As such, we opted to limit the length of our hints to its original intention — a single word.