There are a few different questions that would be beneficial to answer through our prototype for our social deception trivia game, Risky Quizness:

1) Will players actually lie?

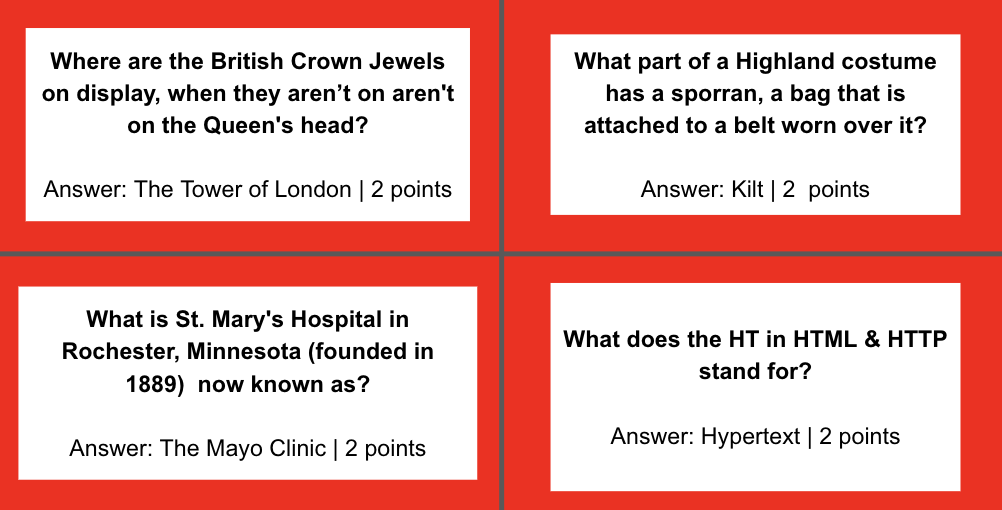

Since we have selected our questions for our prototype from a database of past Jeopardy! questions, it is reasonable to expect that players will actually know the answers to some questions (especially the easy ones). Even if the quizee doesn’t know the answer, it’s possible that one of the other players does. This fact might mean that players always try to guess correctly, rather than coming up with a good bluff. It might also make it difficult to bluff convincingly. This question is critical to answer since the basis of our game is deception and players bluffing about the answers. To test this, we’ll observe players while they play our paper prototype with past Jeopardy! questions. I predict that players might not actually attempt to lie with our current set of questions, and we might have to make the questions a bit more obscure.

2) Are players incentivized to guess correctly whether somebody is bluffing?

One concern that we had while developing our initial idea was that non-quizees would always vote that the quizee is bluffing (since the quizee gets the point either if they guess correctly or they convince others that they are correct). To remedy this, we decided to introduce the mechanic of awarding points for correct guesses of whether the quizee is telling the truth or not. However, we are not yet sure how effective this will be, so it will be interesting to test our prototype and ask people about their strategies for voting. This question is important to answer because it is important to people’s engagement with the game (otherwise, they can simply always vote that the quizee is lying and not actually think about it). I predict that players will actually try to guess whether the quizee is bluffing or not, but they may find it tedious to keep track of it through the “correct guess” cards that we introduced.

3) Do players find it tedious to keep track of timing?

For our prototype, we also introduced a time limit of 10 seconds for the quizee to come up with an answer (to avoid bias depending on how quickly they answer the question), and 20 seconds for them to defend their answer. However, having to keep track of these time limits may quickly become tedious, especially since we are using an online timer for our prototype instead of an hourglass or something more practical. (Ideally, we would test with an hourglass or something more similar to what an actual game would look like.) I predict that having to keep track of these time limits may make the game feel more like a formal high school debate, and that players may prefer to do away with the timer and simply keep track of time on their own / make up their own rules. This question is important to answer because the last thing we want our game to be is tedious — we want players to focus on the interactions and discussions themselves rather than worrying about timekeeping!

4) What do the social dynamics look like (a two-sided debate, a discussion between non-quizzed players, etc.)?

Finally, one other thing that I am very excited to test with our prototype is what the social dynamics of the game will look like, especially with the quizee and moderator changing every round. I think there’s a possibility that the moderator may become disengaged with the game since they know the answer to the question and so can’t participate in voting. Also, it’s possible that the quizee will remain silent after defending their answer, or that they will become very engaged and start a debate with the rest of the players. I predict that people will err on the side of staying silent since trivia questions can be kind of hard to debate over. This question will be important to answer since we want to see what people’s natural inclinations are and how we can make our game more engaging (maybe a type of folding card so that nobody has to see the answer, and thus everyone can participate?).