For this critical play, my friends and I played Spyfall. Spyfall was created by Alexander Ushan, and we used netgames.io to play an online version of the game. The target audience of the card game, self-described as a “hilarious party game,” is players aged 13 and up.

Notable elements

Players and Objectives

The game is designed for 4-12 people. There is one special type of player, the spy, whose objective is to guess the location, and the rest of the players try to figure out who the spy is. This is a unilateral competition, as the players are working to identify which player is the spy.

Procedures

A single round is self-contained, with a single location and single spy. Players can play multiple rounds with different locations and spies and accumulate points after each round. At the beginning of each round, the game designates roles and the location. During the round, players can ask each other questions in turns. At the end of the time limit, players vote for the player who they believe is the spy. If the players vote correctly, the spy has an opportunity to guess the location.

Resources

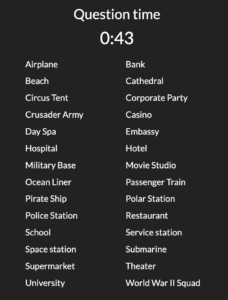

The game provides a list of possible locations that players can refer to during the round. This largely helps the spy to infer the location from a set list of possible locations, and it could also inform the genericness versus specificity of the questions that the players ask.

Outcomes

The outcome is zero-sum: either the spy wins or the players win. At the end of the round, if the players vote correctly and the spy guesses the location correctly, the spy wins. If the players vote correctly and the spy guesses the location incorrectly, the players win. If the players vote incorrectly, the spy wins.

Comparison

Compared to the other games in this genre, Spyfall is relatively similar to One Night Werewolf and Mafia due to the social deception element where one (or more) player is an “imposter” among the group and tries to portray themselves as not the imposter. Perhaps the main difference is that Spyfall only has one special role, the spy, whereas One Night Werewolf and Mafia assign many different roles with varying complexity. Personally, the diversity of abilities and gameplay that the latter provides makes for a more nuanced, engaging game that sustains freshness even after playing the game multiple times. However, roles in One Night Werewolf and Mafia can often be quite imbalanced, leaving some players (i.e. villagers with no special powers) with way less opportunity to engage and interact. In Spyfall, rather, all players that aren’t the spy are equal, making it so that everyone can ask and answer freely and creatively, turn by turn.

Was the game fun?

Overall, I did generally enjoy the game. The first couple of rounds were exciting to me, because it felt like a challenge to be able to strategically ask and answer questions. How generic or specific should I be to both (1) prove to everyone else that I am not the spy yet also (2) not give away the location to the actual spy? I personally was also the spy several times, and though it did sometimes feel like I was not the “in group” because I did not have information that everyone else had, I thought it was fun and motivating to try to infer as best as I could from everyone else’s questions and answers. After a few rounds, however, the content became more and more repetitive, as people began asking roughly the same questions. We also got to know each other better as players and spies, making it relatively easier and more obvious to determine whether someone was the spy or not. Since these aspects of the game were less novel, it also made the game less fun and enjoyable. In the future, I would probably also play the game with more people (we played as a group of 4), as this will increase the difficulty of guessing the spy.

Moments of particular success or epic fails

One small fail was during the first round, for which I was the spy. Only three questions were asked, and I for some reason already came to the conclusion that I knew the location and decided to reveal myself as the spy. Unsurprisingly in hindsight, my guess was quite incorrect. This fail, however, and more familiarity with and understanding of the complexity of the locations, helped me have a moment of particular success. This moment was when I was a spy and correctly guessed the location at the end of the round. It was stimulating as the round progressed, because I was starting to latch onto more and more threads that gave me insight into what the location might be as the other players asked and answered more questions. Thus, when the round ended, and they correctly guessed that I was the spy, I already felt pretty confident about what the location was, and indeed, it turned out to be correct.

One epic fail for the group was when we reached deadlock. The vote was even and ultimately came down to two people’s votes, but these two people were pretty much unwilling to budge. This took a good amount of time to break out of. Ultimately, one player did change their vote, because of the game rule that the vote must be unanimous to accuse someone of being the spy.

Improvements

- We felt that the selection of locations was not only limited but a bit odd. Most locations were actual physical locations, but there were also some locations that were events (corporate party) and time periods (Crusader Army) and just a bit random. Perhaps the locations could all be common—at least well-known and understood by the average person.

- Perhaps there could be a different set of locations for each round or versions of the game that revolve around people, objects, events, etc. These changes would aim to increase the novelty of the game, as the set list of locations felt repetitive and made the game feel limiting.

- Given the struggle we faced with the deadlock epic fail, perhaps instead of being forced to reach an unanimous vote, we would just need to reach a majority vote. This would help to continue the flow of the game when the players get stuck.