The game I played was Spyfall, a social deception game created by Alexandr Ushan for young adults. The original version is a card game, but I played one of the several online versions.

As described above, Spyfall revolves around a group working to figure out which one of them is the spy. It’s a unilateral competition where if they do, everyone but the spy wins. Meanwhile the spy actually has two paths to victory – staying undetected or being able to guess the group’s secret location. Ultimately, there are still two basic outcomes: the group or the spy wins. But because of the location mechanic, Spyfall opens up a few more nuanced ways for the game to end despite the simple objective presented.

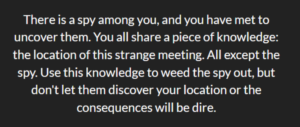

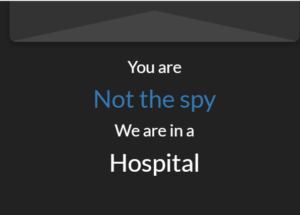

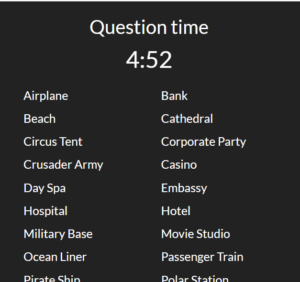

But first, let’s step back and take a proper look at the rules. Spyfall requires 3+ players (I played with 5) and at the start of the game, everyone is randomly assigned a role. After everyone has checked their role, the game proceeds to reveal a secret location, chosen randomly from a list, to every player except the spy. After everyone has checked this location, a timer begins to count down as the group is allowed to begin questioning. In the version I played, we were given 5 minutes.

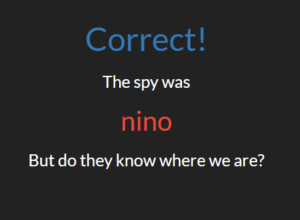

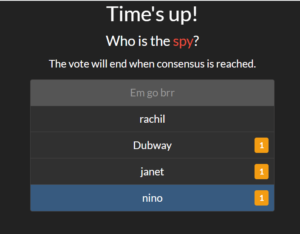

Each round of questioning involved each player taking their turn to ask any player of their choosing a question about the location, who would then have to answer. This line of actions continues going until the time is up, and then the group can discuss who they believe the spy to be. Once the vote is unanimous, the game reveals whether the guess was correct. If not, the spy wins! If so, the spy has one more chance to win by guessing the location correctly. If they don’t, the group wins.

We’ve seen many, many versions of games like this before, where the goal is essentially to weed out the “bad” player. So what makes Spyfall different from say Mafia, Secret Hitler, or Press the Button? Like I mentioned, the unique location mechanic does more than one would think.

Given how relatively short each game is, we played four times. Each time resulted in a somewhat differently nuanced outcome. In the first, the spy won by guessing the correct location. In the second, the spy lost by being found out and also guessing the location incorrectly. In the third, the spy won by not being found out, despite not knowing the correct location. And in the fourth, the spy won by not being found out while having figured out the location.

“Okay, well don’t say too much now, you don’t have to elaborate!”

As we played, we found the game getting more and more enjoyable in subsequent rounds as we got more familiar with how it worked – achieving greater mental mastery, say. It was fun to challenge yourself in creating more interesting questions to draw out information as well as give cryptic but knowing answers. The need to walk a balance of how much information to give paired with the flavor of spies and agents as a setting gives the game more of a sneaky, measured feel. There is no repeated singling out and kicking people from the group, but rather a continued observation until the group comes together to decide who was acting the most suspiciously. The importance of asking good questions and giving good answers means that everyone is focused on their individual performance. Hence, I found the design of having locations and questions, with an additional way for the spy to win, very effective in distinguishing the game and creating a new kind of fun in a saturated genre.

“I was able to figure out it was a school.” “It was a circus tent.”

“I was so confused by your answer, it threw me off and so we stopped asking Tony questions…”

As players new to the game, there were quite a few funny hiccups. One example of a “fail” for the spy would be in our second game, when a player was unable to stay hidden nor guess the location – he explained later that someone had asked if the location served food, which made him think it was a restaurant instead of a hospital. Another instance of failure, but for the group, was in game four. The spy player answered questions correctly but vaguely, and slipped under the radar when another player answered a question in a strange way, catching attention. On the other hand, in game three, the spy player had a particular moment of great success – not only was she not caught, in the discussion, the rest of the group pointedly thought it couldn’t be her!

“I’m not sure who it is, but I don’t think it’s Janet.” “Yeah, I’m confident it’s not Janet.”

Ultimately, the games ended up with spies winning most of the time. Perhaps this would change if we played even more, but I believe there could also be ways to help balance this out and make the game even more enjoyable. For instance, the timer didn’t feel particularly helpful in terms of adding fun to the game or getting people to ask and answer more quickly. The priority was always giving a good question or answer, so despite the clock ticking down, people did not respond more quickly. Instead, it ended up feeling like the group didn’t have enough time to question, not everyone was questioned as much as we would have liked, and formulating questions themselves was tough in the constraint. This also made deciding on a unanimous spy more difficult and based more on whim than suspicion. One suggestion to fix this was to have the game decided by rounds – for example, three cycles of every player asking a question. This way, we could get higher quality questions, gain more information, and therefore have more complex games.

Overall, though, my friends and I had a lot of fun playing Spyfall, and – perhaps with our own modifications – look forward to trying it again!