Overall, it’s more niche than other games in the social deception category, but if you enjoy roleplaying and don’t have a lot of time to commit, Inhuman Conditions can be a good bout of fun for two.

I played Inhuman Conditions with Michelle, a partner from my project group. The game was originally created by Tommy Maranges and Cory O’Brien and illustrated by Mackenzie Schubert. Collectively, these folks have worked on Secret Hitler, Monster Prom, Philosophy Bro, and other notable titles. FTWinston created the web app version of the game that Michelle and I played over Zoom.

Inhuman Conditions boils down to a fun little “forbidden action” meets “social deception” game. The twist? Only one player knows the forbidden action.

The game lasts just five minutes and is comprised of a staged interrogation involving two players, the investigator and the suspect. Throughout the conversation, the investigator’s goal is to determine if the suspect is a robot (i.e. their speech is bound by a secret forbidden action, think, “You can only speak in the present tense”) or a human (in which case there’s no forbidden action). Of course, the crux of typical forbidden action games is that everyone knows what the forbidden action is—that’s what usually makes it fun. Inhuman Conditions takes another perspective, in which only the suspect knows the forbidden action. This ends up being loads of fun for both players, since the investigator needs to find out if the suspect is speaking suspiciously because they’re or robot or if they’re just, y’know, a nervous human. Suspects are also given a “character” card ranging from “Popstar” to “Dean of Clown College” meaning they answer all questions as if they were really that fictitious role, making this a roleplaying story game as well.

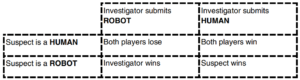

Formally, the game’s structure is a 1v1 player vs. player game. The interesting thing about Inhuman Conditions as opposed most “forbidden action” games is that the forbidden action only binds one player, making the player vs. player structure asymmetric rather than putting everyone on the same playing field, like in Taboo. This also means the players’ objectives are asymmetric: the investigator is trying to find if a forbidden action exists (i.e. the suspect is a robot), and the suspect is trying to convince the investigator that there’s no forbidden action (regardless if they’re a robot or not). At the end of the five minutes the investigator guesses the role of the suspect, with one of four outcomes based on if their guess is correct or not (see the handy table below).

Possible outcomes based on the players’ secret roles.

Regardless, the gameplay structure of Inhuman Conditions can be summed up as: two-person interrogation with lots of unnecessary obstacles that end up producing a lot of fun

It’s a short game, which works to its benefit since players can switch up roles often, keeping the game fresh. It also works as short game since it’s fairly whimsical and low-stakes, i.e. it’s not a game you play to win so much as you play to have fun and laugh, and five minutes feels like a reasonable investment for such a game. This isn’t to say that winning and losing is absent, but more accurately that winning and losing feels arbitrary, because the real fun of the game is in the storytelling that happens in the interim. In this sense, I see Inhuman Conditions toeing the line between “game” and “toy.” It has game-y qualities because it’s still a competition between two players where one emerges victorious. But it’s also edging on a toy, because it’s really just there to facilitate funny conversations, rather than to separate winners from losers. Regardless, the gameplay structure of Inhuman Conditions can be summed up as: two-person interrogation with lots of unnecessary obstacles that end up producing a lot of fun.

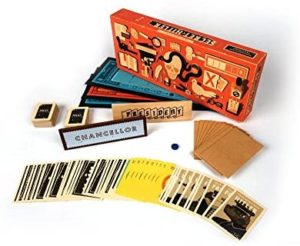

We can discuss the gameplay structure of Inhuman Conditions separately from its narrative wrapping, which ends up being a whole different topic. It’s unsurprising that the creators of titles like Monster Prom (which drips in lavish narrative-based gameplay) and Secret Hitler (a notoriously sleek and sexy game) created a game with as much narrative flair as Inhuman Conditions has: in the game, you’re not just called the investigator: you have paperwork to fill out (pictured below)! You’re not just a robot, you have “malfunctions” and shake hands stiffly (seriously, this is part of the rules). These are just some of the superfluous mechanics that the game includes in order to sell this narrative of a high-stakes police interrogation.

The physical game is chock full of physical artifacts that help sell the roleplaying fantasy. The investigator’s “Form VK-82(e)” paperwork even requires you to collect your suspect’s email address.

For me, this commitment to narrative ends up being the double-edged sword by which Inhuman Conditions both soars and falters. It’s a pure storytelling game, which means of the eight types of fun we defined in the class, Inhuman Conditions commits hard to narrative and fantasy. That is to say, in my experience, none of the forbidden actions were especially fun by themselves. What was fun, though, was getting to step into the shoes of a character. Example: at one point, I played a robot posing as a used van dealer who couldn’t speak in the past tense. As a robot, preventing yourself from speaking in the past tense isn’t really all that interesting alone. What was hilarious was when Michelle, posing as an incisive police investigator, asked me about what I’d done the previous weekend (remember, I can’t speak in the past tense), and I got to make up a story about how I hate my job selling vans because it feels like ripping people off, and on and on and on, completely avoiding her question. It was hilarious! In this sense, the narrative possibility is the real gem that Inhuman Conditions offers.

For me, this commitment to narrative ends up being the double-edged sword by which Inhuman Conditions both soars and falters.

At times, though, this commitment to narrative is a little distracting. While the game is simple enough to understand for all ages, I do think that it takes a bit of constraint to understand that the fun of the game is in the storytelling rather than the gameplay, meaning that unimaginative or misguided players might find the game boring. At other times, the commitment to narrative inhibits onboarding: for example, the rule book is written as a fictitious police investigation guide, making it a little hard to understand. Case in point, “Setup” is called “Intake Procedure” and fluffy lines like “Most importantly, the documentation ensures that the interview will be admissible in court” are sprinkled throughout. For someone who had never played the game, the jargon and narrative bells and whistles made getting into the game more difficult than necessary, which is particularly frustrating for a game that is designed to be short, whimsical fun. As a designer, I would’ve let the game serve as the narrative vehicle, and left the rules and procedures as sterile need-to-know type documents.

The game’s stamps, paperwork, and even the board are all not strictly necessary for gameplay, which both helps and hurts the game.

Inhuman Conditions does still have an array of high marks, though, not least of which is how well it sparks conversation that helps you get to know another person. This isn’t fun persay—I’d probably call it enjoyable instead—but this is still a merit. At one point I was telling Michelle a (true) story about the first time I learned to ride a bike, which felt surprisingly intimate in a game otherwise filled with lots of giggling (keep in mind, I was telling her this story while playing the role of robot posing as a former newspaper salesman). I think the propensity to spark spontaneous conversation is a result of the game’s commitment to narrative (i.e. it’s easier to tell her this story “because I’m playing a character” rather than something deeper), which reminds me of the wild popularity of We’re Not Really Strangers (also more toy than game).

The creators of Inhuman Conditions also made Secret Hitler and Monster Prom!

Compared to its more popular step-siblings Secret Hitler (social deception) and Monster Prom (narrative fun), Inhuman Conditions isn’t plainly better or worse than them but serves a different purpose. It’s a little less polished than either of the two (some of the penalties are too obvious, the gameplay gets a little repetitive since there are only two players) but it definitely takes less investment than the other games, which is nice if you just want to kill a short amount of time with a friend. I’d say it’s probably less popular than the other two since it fails as a party game—that is, it’s only played between two players, which makes it hard to play in group situations, which are more common than 1v1 settings in my experience. Moreover, its reliance on narrative is probably hit-or-miss for players, since you have to be willing to roleplay a fictional role to have real fun, and some people are probably embarrassed by this. Overall, it’s more niche than other games in the social deception category, but if you enjoy roleplaying and don’t have a lot of time to commit, Inhuman Conditions can be a good bout of fun for two.

P.S. I should nod at the fact that Michelle and I played a web app version of Inhuman Conditions instead of the physical game. This ended up being a moderate detriment to the experience, since, as it turns out, a lot of the fun of playing a narrative game comes from the physical artifacts that let you get into that fictional role. It’s kind of a shame that the web app distilled the investigator’s “Form VK-82(e)”, for example, into just a simple text block. This should be taken as a testament to how important the narrative wrapping is to the success of Inhuman Conditions.