For this week’s Critical Play, I explored Super Smash Bros. Ultimate (SSBU), which was developed by game designer Masahiro Sakurai. The game is available on the Nintendo Switch. In this Critical Play, I use a feminist lens to explore and critique the game experience. SSBU includes multiple game modes, including a PVE storyline (with battles) and PVP or PVE battles (“Smash”). For this Critical Play, I examined the traditional PVP/PVE “Smash” battles as they are the most prevalent and well-known part of the game (if a friend asks you if you want to play Smash, this is almost always what they are referring to).

Generally, SSBU is meant for young adults (target audience) who are interested in fighting games (and who might have played previous Smash games). Throughout the rest of this Critical Play, I will further narrow down on this target audience—specifically with respect to gender and the extent to which SSBU is more targeted toward cis-men than cis-women and trans or non-binary people. Specifically, I will use a feminist lens to look at the character selection aspects of SSBU to argue that, although there are positive feminist elements of character selection, SSBU still falls short in key areas.

To begin, SSBU’s Smash Mode is a game where players fight as characters from a number of other game universes. For example, you can play as Pokémon from Pokemon or as Link from Legend of Zelda. In SSBU’s Smash Mode, you win by being the last player standing (or, in some Smash game configurations, the one with the highest net number of “kills”). This game mode is competitive and involves fighting—something traditionally seen as masculine. In the same way that industry specifically created and marketed games such as FPSs to men in the mid-1980s and onward, it’s clear that the predominant narrative within SSBU may generally be seen as more masculine. This is important culturally, as it links with the idea of trying to make male-oriented spaces more safe and appealing to non-male audiences. According to Bartle’s Taxonomy of players, this game type most evidently appeals to Killer-type players (the game involves fighting and beating others). Note though that it may also appeal to Socializer-type players (SSBU is a game that people will also want to play casually for fun with each other as opposed to competing more seriously).

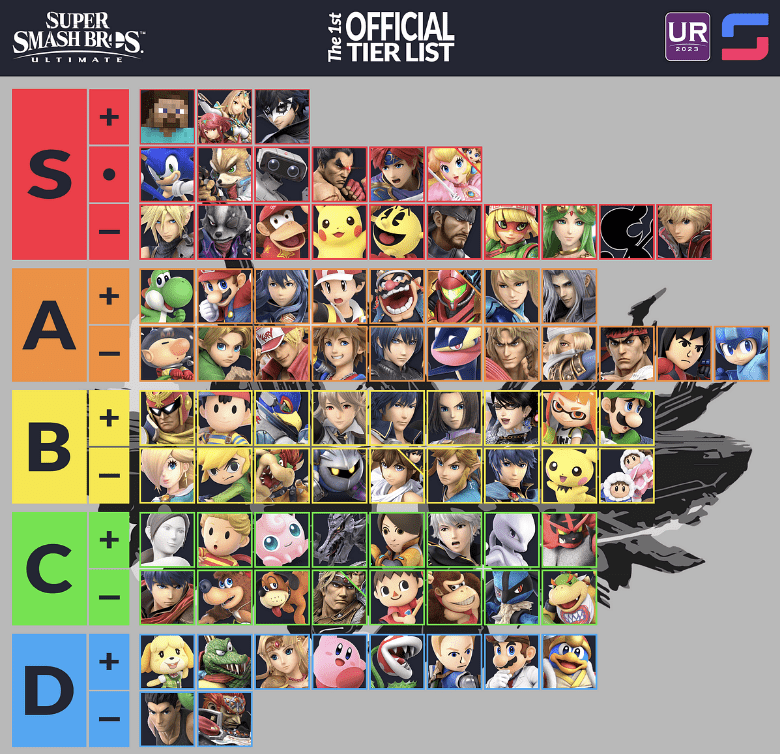

At a most basic level, we can look at the amount of female representation within character selection in Smash: what percent of the characters are women versus men? A quick glance at the character roster (see screenshot) shows that, despite there being female characters to choose from, they are outnumbered by male ones. From an intersectional perspective, there are few characters that represent people of color (ex: Ryu), and even fewer that represent women of color (ex: Min Min—who is a special pay-to-unlock DLC character—this links in with the concept of a pink-tax and games involving consumption within a capitalist system). Nearly all of the POC representation is East Asian, leaving out Black and Brown characters. From a queer perspective, despite there being an explicit presence of trans representation, Link was explicitly designed to be relatively androgynous, and many trans players have seen themselves in Link. To the best of my knowledge, there are no disabled characters within SSBY. Although there is some level of representation of marginalized groups within SSBU’s character roster (see image below), there is absolutely still room for improvement (critique) with regard to gender (among all groups apart from cis-men), race/ethnicity, disability, and more, along with the intersections between those groups.

To take this analysis further, we can look at the extent to which the female character options are stereotypical and whether there is a diverse set of female representations that may appeal to different women. Women are not a monolith, and designing female characters should not be a “one-size-fits-all women” pursuit. Stereotypical female characters include Peach (a pink princess whose special move involves hiding behind Toad—a male character, see image), Zero Suit Samus (blonde with tight clothing), and Bayonetta (heavily sexualized with high heels that are used as weapons). There is room for improvement (critique) for SSBU to add more characters representing diverse options of what it means to be a woman.

Representation is not the end of the story. It’s also important to make sure that female characters are not disproportionately disadvantaged within the game relative to their male counterparts. I polled some friends who play SSBU more than I do, and they did report that female characters did not seem overly disadvantaged in the game—in fact, Peach is one of the best characters. See the below tier list:

In some games, character selection is fixed in that you pick your character at the beginning of a long storyline and continue with that character throughout. In SSBU, games are short (usually only a few minutes—this also links with a feminist discussion of time, including who has time to play different types of games and who has time to get good at them), and players have the opportunity to try out new characters as they desire. This adds agency to the game. Accordingly, In SSBU, it’s not seen as weird for women to play male characters or for men to play female characters—generally, there is no expectation for one’s gender in real life to “match” the gender of any character they play in-game. This makes character selection in SSBU relatively safe for closeted trans players and is a win for gender inclusivity in general.

Finally, recall that SSBU has characters from other Nintendo game universes. This is generally positive in that it reduces the barrier to entry for games—players can get excited to play the SSBU if they already know another character from another Nintendo game. However, note that, historically, Nintendo (and other large game companies) have had much room to improve with respect to representation within character selection. Future iterations of Smash ought to draw upon increasingly diverse sets of characters as Nintendo itself continues to improve in that regard (critique).

In conclusion, SSBU’s character selection has some positive feminist elements, but it still absolutely has plenty of room for improvement. In order to truly effectively appeal to a more diverse target audience, SSBU must improve. In this Critical Play, I looked mostly at some of the mechanics in-game related to character selection. However, by nature, SSBU is a social game—with that comes a broader community of players. In light of GamerGate and the lived experience of gender-marginalized players of SSBU and other games, further discussion around the following question would be important: to what extent are games’ feminist inclusivity defined by their programmed mechanics versus their communities?