Storyteller is a mechanically brilliant game developed by Daniel Benmergui. In it, you must arrange different characters and settings correctly to match a provided title. Although I bought it on Steam for $15 and played it through my Friday, the game is also available across Android, Nintendo Switch, and iOS. This game is a must-try for any casual puzzle-loving gamers or storytelling enthusiasts. However, it has light themes of death and heartbreak, so perhaps it’s not for extremely young audiences.

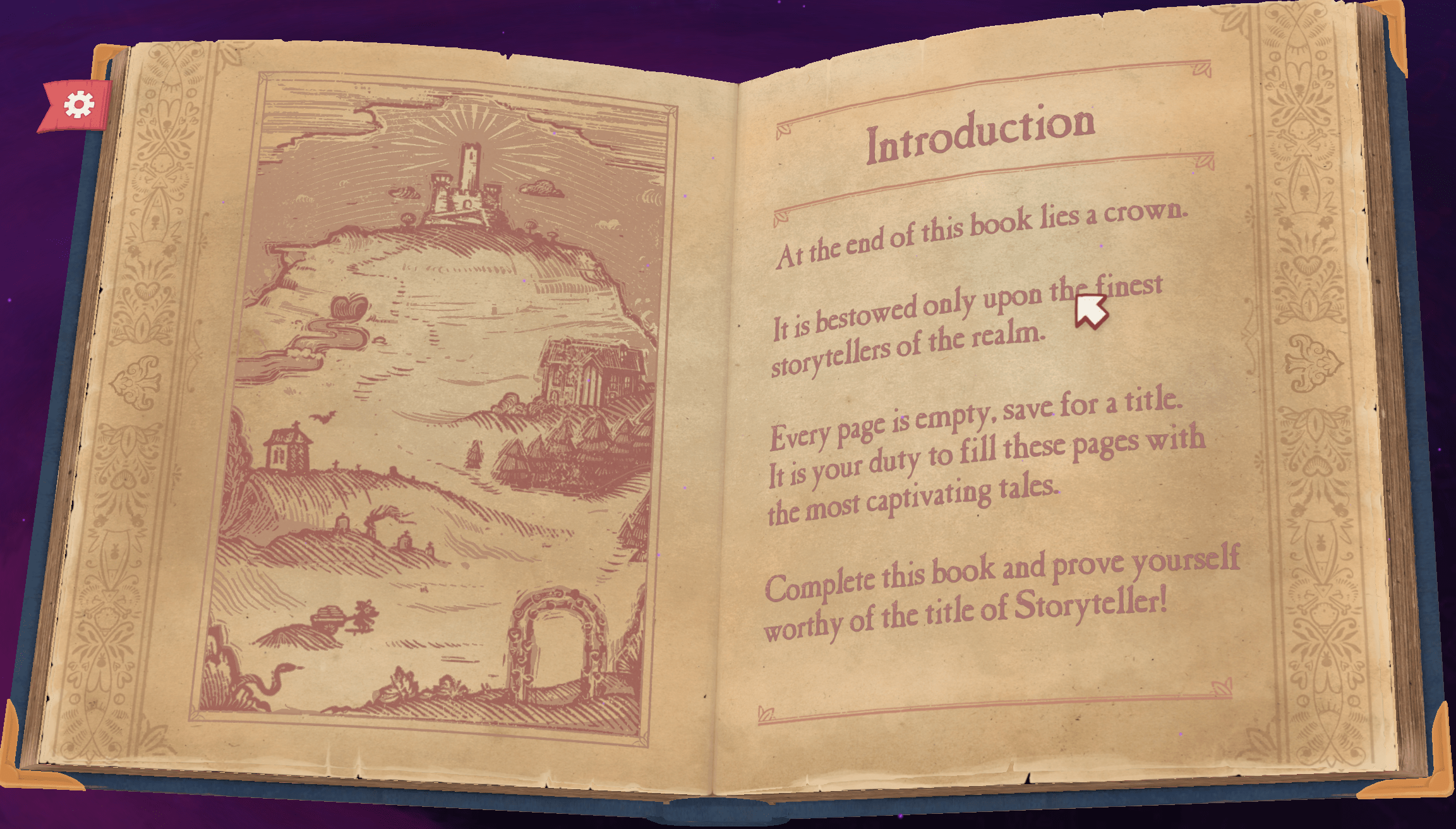

Figure 1: An image of the beginning of the game, which provides a brief introduction that explains the narrative rather than the mechanics

The first thing I saw when I opened the game was a large book on the screen. Little did I know that this would be the most text I would see explaining the game’s purpose. The rest of the game was full of puzzles, abstract storytelling, and text that was more cryptic than helpful. This intentional lack of strict guidance, paired with drag-and-drop blocks that fit into random slots, comprised the game’s mechanics. However, rather than making the game cryptic and frustrating, it made the game feel more experiential and the outcomes even more accomplishing, being less handheld.

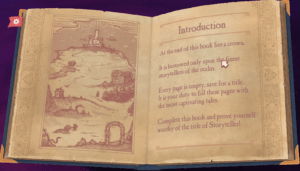

Figure 2: An image previewing how the game decides to teach its mechanics (notice the arrow with the text “scenes” before it)

Rather than feeling confused, this prompted me to try out multiple configurations since there was no punishment for error. Sometimes, I would even try out random combinations without trying to go for a “solution”—like when I made the knight, who typically ends up antagonizing the baron, marry the baron instead (shown in the figure below). This trial-and-error process is integral to the game, pushing players to explore narrative possibilities and understand the consequences of their choices. These mechanics shift the game from a potentially frustrating puzzler to one of experimentation and creativity. To me, these surprising and humorous outcomes helped keep the gameplay engaging. On a separate point, experiencing this game through the lens of a game developer and watching all of these possibilities accounted for really impressed me.

Additionally, the game provides instant feedback on the player’s choices. Even while testing and moving my story’s elements around, on rare occasions, the story was sometimes accepted for the lack of my intention to do so. Despite these happenstances, this immediate response helped me better understand the game’s logic and encouraged them to think about why specific stories worked.

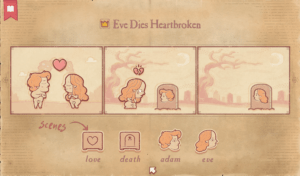

Figure 3: An image demonstrating how the game’s trial-and-error can lead to funny outcomes that aren’t directly related to the level’s goal

Daniel Benmergui knew that one of the strengths of his game was this trial-and-error, so he also formulated some levels where the player could form different stories using the same assets. This mechanic was one way to easily prolong the game while forcing the player to think more deeply about the interactions between the characters and settings. Nothing was more satisfying than completing the level, getting another prompt, and then completing the level differently. Just a shift of motivation and information can lead to entirely new pathways.

This inclusion is exciting because it also demonstrates the power of a narrative’s direction. By solving these puzzles, the player experiences different tropes and narrative components like conflict, resolution, character motivation, and emotional arcs… all without direct instruction! Simply playing this game made me feel like I had covertly learned a bit of storytelling and literary analysis.

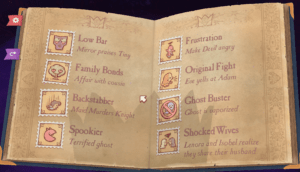

Figure 4: An image detailing a level that allows for “multiple pathways” by requiring a different orientation of settings/characters

Eventually, after a total of three hours, I completed the game, including all of the achievements (it was just that precious to me!) Overall, Storyteller is a masterfully crafted puzzler, and after noticing that it won an award (see the game’s 2012 prototype below), I wasn’t even the slightest bit surprised. It’s a very original idea, despite the narrative tropes within it.

Although I’m a bit tempted to say that the lack of puzzles or elements within the puzzles is the main downside to the game, I also acknowledge that having too many elements could make the game more frustrating. Additionally, it would probably create an exponential amount of possibilities for each added element since it creates even more possibilities through combination. As I look ahead to developing our P2 game, I acknowledge that cutting corners and keeping things simple may be the way to go—both to balance the game’s complexity to reduce player frustration and to lessen the workload of me and my team members.

Figure 5: An image showing a prototype of the game in 2012, which won an award! (found off Wikipedia)

Figure 6: An image of my accomplishments by the end of the game, earning every achievement!