Our current concept (Fake Friends) is a social deduction game where one friend relays a secret to other friends, while “fake friends” aim to leak it to “enemies,” who shouldn’t know it. Fake friends wish to cause chaos and discreetly relay information to enemies, while real friends strive to learn the secret without leaking it. Our group has thus explored social deduction and cooperative games with communication restrictions to formulate our mechanics. For my comparative analysis, I will examine a social deduction game played: Spyfall.

Created by Alexandr Ushan and published by Hobby World, Spyfall debuted as a physical board game in 2014, with online versions currently available. Playable with 3-8 players, Spyfall is intended for ages 13 and up, and is marketed as a “hilarious party game” appealing to a broad spectrum of players. I played an online version with 4 players in the same physical room.

Spyfall and our concept share essential dynamics surrounding player interaction and communication: Spyfall makes players balance risks associated with simultaneous information gathering and exposure under time pressure, forcing players to make quick, strategic decisions while forming necessary deductions. However, our game differs in interpretation of minority players’ (spies or fake friends) roles, win conditions, and immersion.

Both Spyfall and our concept assign players roles, with timed discussion during which players must outwit opponents to gather information without exposing information. In Spyfall, this is maintained by the mechanic of the spy winning—even if exposed—by guessing the location. This unites non-spies to cautiously ask questions to prove their common knowledge without revealing too much, creating a sense of fellowship. Likewise, the spy must discreetly curate questions to gain information towards the location. Consequently, both roles ask questions with an aspect of fear of revealing too much.

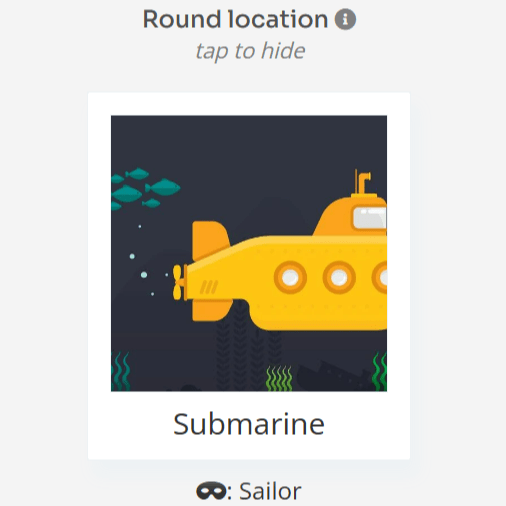

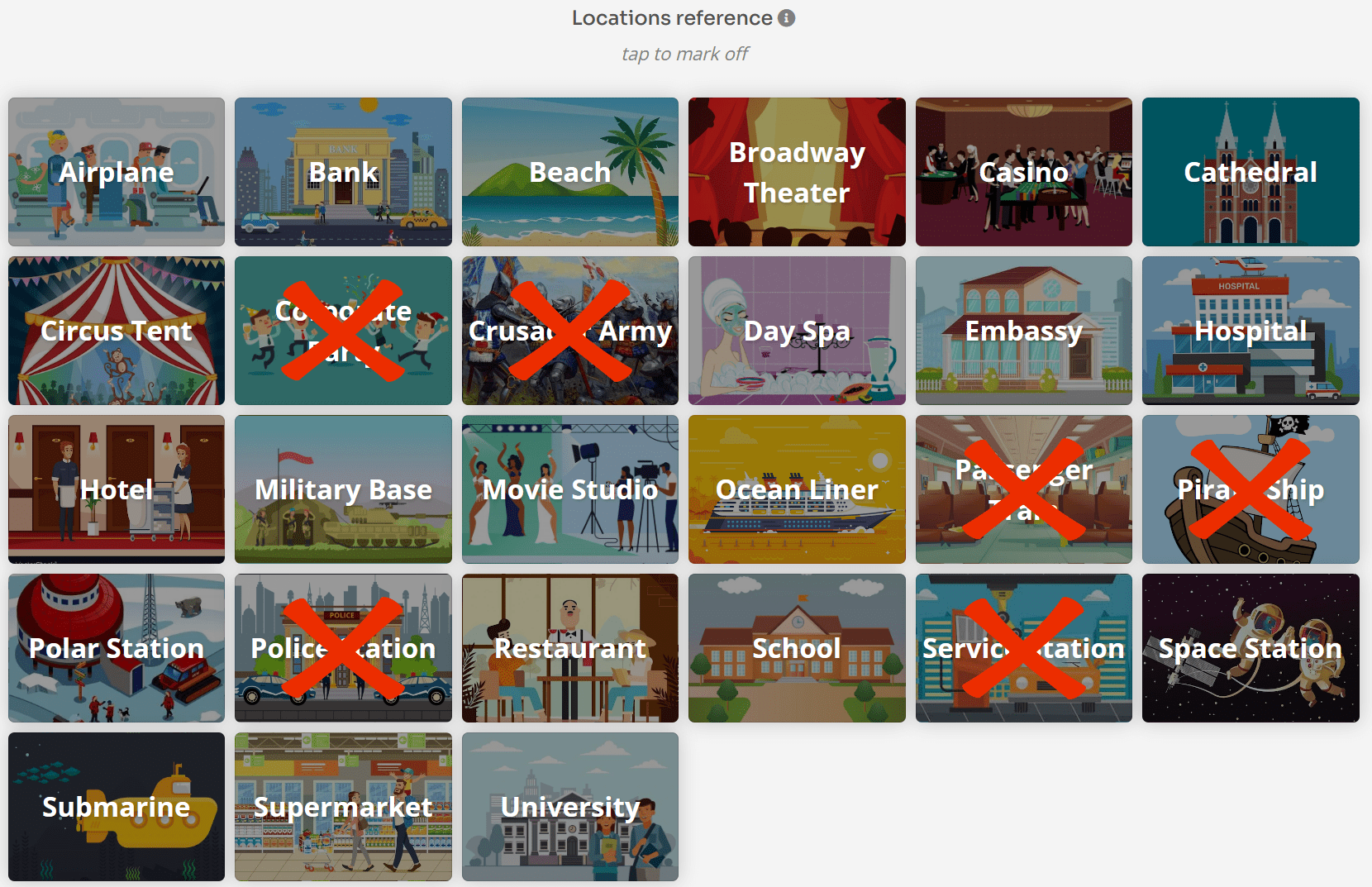

This fear is counterbalanced by a universal, limited resource: time. In my rounds, players tended to ask riskier questions as time became scarce, once they realized that they lacked information to win. In one round, I didn’t know who the spy was until they asked, “Is there a song about this location?” Our location was the (Yellow) Submarine, so this question could expose the answer if asked by a non-spy. I instinctively answered “yes” due to time constraints, but looking back I should’ve tried to obfuscate. The spy in this case blew their cover to confirmation the location, securing the game—meanwhile, time pressure made me provide a suboptimal answer. The balance of informational exchange against the clock created adequate challenge for both teams, despite it being a unilateral competition of one spy versus other players. I found this to cleverly balance the game: everyone feels anxiety and desperation as time narrows.

The primary differences between Spyfall and our concept derive from Spyfall’s flaws. Spyfall’s simplicity (such as being limited to asking 1 question at a time without counterquestions or responses) allows for easy entry, but limits gameplay variation, making it quickly become stale. In contrast, our secret derives from pre-selected words, similar to Mad Libs. This adds humor to our game due to absurd word combinations, and also, such randomization and personalization increase replay value.

Likewise, roles in Spyfall felt unfulfilling. Similar to “A Fake Artist Goes to New York,” the minority (spy) role is demoralizing: in one game with the spy going first, resultingly lacking any information on the location, they immediately asked a suspicious question implicating them. The game became a constant interrogation before unanimously voting for them (correctly). From a design perspective, the spy role easily feels unfair and alienating by random change by random chance (35% with 4 players), While this introduces challenge for the spy, it makes the game through the spy’s lens truly unilateral, and downright frustrating to play. To avoid such sentiment, fake friends will be powerful and desirable, not vulnerable—akin to Mafia. An example of power would be receiving hints about the secret, to help fake friends avoid exposure. Additionally, exposure in our game wouldn’t result in real friends winning: they must still discover the secret without enemies doing so.

Lastly regarding differences is immersion. In prioritizing simple gameplay, Spyfall sacrifices thematic aspects contributive towards the game’s Magic Circle. It never feels like players are true detectives, or that the locations are relevant to an overarching narrative.

Because of this, no dramatic element of fantasy/roleplay exists within the game’s aesthetic. Our game intends to focus heavily on friends, with specific terminology that allow the Magic Circle to easily be entered and exist.

While Spyfall is a simple and excellent starting point for a social deduction game focused on verbal communication, our concept will address major issues that negatively affected Skyfall’s player dynamics contributing to fun.