A Fake Artist Goes to New York, developed by Japanese board game designer Jun Sasaki, positions its 5-10 players in an art exhibit, required to collaboratively generate a beautiful piece of art for a “massive exhibition.” The only problem is that one of the artists is “fake” and does not receive the topic as everybody else does. They are required to blend in, with the help of the question master, to go undetected by the other artists (who, clearly, know what they’re doing). With an age rating 8+, this game is designed for practically anybody to play—even young kids!—with no requirement for drawing skills. (In my critical play, I even found that a “lack of drawing skill” can make the game more fun, adding some interest as everyone questions the reasoning behind a specific line.)

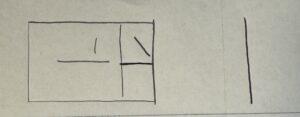

The game is primarily designed to be played in person, although not having the official set can still warrant gameplay through index cards and pencils (which is how my group played!). One core difference between my critical play experience and the actual card game was the absence of multiple colored markers, which made it a bit trickier to draw connections between the lines and the actual players. However, we based it on the honor system and asked people to elaborate on which lines they drew. It still led to an overall fun experience! The main aesthetics I felt through the game were ones of fellowship and expression; it was always great to see the big picture at the end of the game (see an example below). There also was a bit of challenge and some strategies that arose, with people becoming more and more daring with their choices as the game progressed (to weed out and confuse the faker).

Figure 1: A re-enactment of a “schoolbus” that my group drew; my line finished off the right side of the bus (as the faker).

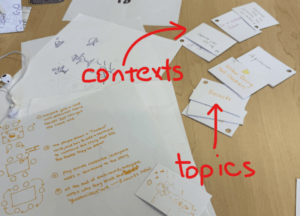

This game parallels the game my group is developing, titled Ghostwriters. Ghostwriters also has one person as the main facilitator who draws N-1 cards (where N is the number of other players) from a stack of topics (e.g., beach, aquarium, chicken). The facilitator must then copy one of the topics onto an empty card and distribute the cards among the other players. Where A Fake Artist Goes to New York has one “faker” who has no idea what the topic is, Ghostwriters has two “ghostwriters” who have the same topic. The objective is similar: players must guess who the two “ghostwriters” are, akin to guessing who the “faker” is after a round of A Fake Artist Goes to New York. Additionally, instead of drawing a line onto a sheet of paper, players continue a story from an initial “context” card. Why these modding choices? Mainly for two reasons, both of which I will expand upon in this critical play.

Figure 2: An image of a prototype of Ghostwriters, showing some examples of self-designed topics and contexts.

Firstly, guessing a “faker” based on a drawn line was extremely varied in difficulty. In a round where I was the faker, I slipped by with zero votes by continuing a line another player drew. In others, catching the faker was unnecessarily easy with a seemingly random line that was difficult to rationalize. To preserve the light and humorous “expression” aesthetic (through players adding lines that contributed to a bigger picture) in A Fake Artist Goes to New York, my design team replaced the drawing aspect with another form of creativity in Ghostwriters: storytelling. Giving everybody a piece of information (as opposed to giving somebody no information) makes the game less difficult to deceive other players. Additionally, in Ghostwriters, everybody struggles with the fact that they could be a ghostwriter, incentivizing people to still be vague yet obvious with their lines.

Secondly, the amount of player interaction in A Fake Artist Goes to New York sometimes fell short. While being able to contribute to a drawing sounds fun, only drawing one straight line and then waiting your turn again is less so. Players have less space to express themselves every turn as an intentional mechanic, making it more possible for the faker to get by. However, in Ghostwriters, we wanted to emphasize our players’ self-expression. To allow players to engage more with their topics, they instead must narrate a story—which requires much more work than drawing a single line. This shift also results in a game with a more satisfying end product. Rather than ending up with an obscure image, an entire narrative was laid out before us. In one playthrough, we ended up with a story that involved (a) bringing a towel to a beach, (b) eating Wilbur Dining Hall chicken, and (c) taking insulin before an epic battle to the death.

But I don’t want to simply claim that Ghostwriters is perfect and better than Sasaki’s in every way. There are a few flaws I can also identify in our game, which we’ve yet to prototype and fully patch. One is that, whereas, with A Fake Artist in New York, you can visibly see the picture that your group’s efforts have made, in Ghostwriters, whatever is said is not recorded anywhere, becoming lost to the void. It becomes much harder to remember which player said what under these circumstances, leading to points where the players forget what they’ve said. I speculate this may require some sort of log or digital entry to not rely on player memory. I’m hoping to get these kinks further worked out in future testing!

Figure 3: The cover image of A Fake Artist Goes to New York, by Jun Sasaki

In short, I guess you could call Ghostwriters a version of A Fake Artist Goes to New York, but with (a) the drawing replaced with storytelling and (b) the “faker” replaced with a team of two identical “ghostwriters.” But you won’t get a narrative as thrilling as the ones you find in Ghostwriters in the latter. After all, it requires more wackiness to discreetly fit “diabetes” into your story of an epic battle, over drawing a random line to finish up an incomplete “school bus.” 🙂