Spyfall is a social deduction game created by Alexandr Ushan, an award-winning Ukranian game designer. It was intended to be played by those above the age of 13 and in groups of 3 – 8. Ushan initially created the game as a card-based platform that has since been re-developed into an online version following the same rules as the original. Using this online version, my friends and I played a game of Spyfall as a group of 8. Through this experience, it has become clear that Spyfall emphasizes social deduction by compelling players to carefully balance sharing and withholding information to uncover hidden roles as the non-spies or maintain their cover as the spy. Specifically, by employing asymmetric information distribution, open-ended questioning, and compelling objectives, Spyfall creates a memorable social deduction-based game experience.

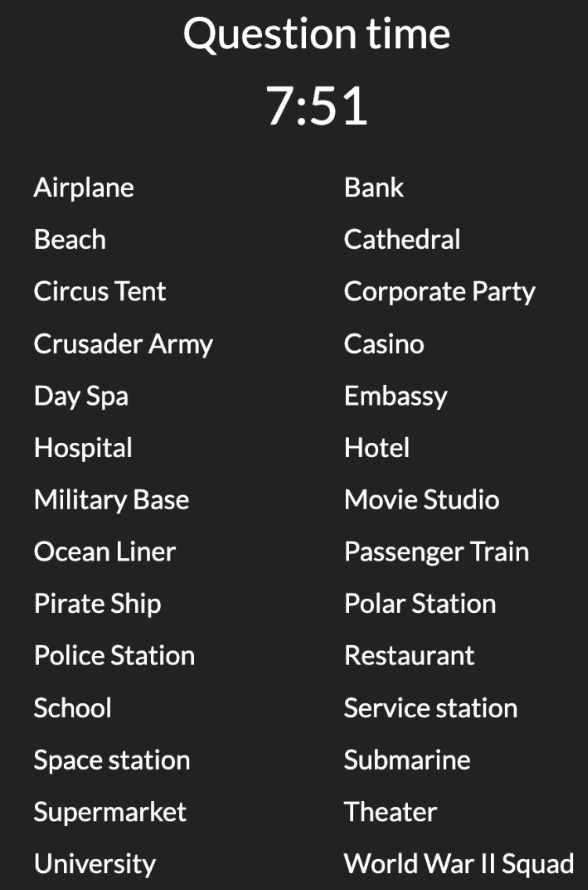

At the core of Spyfall’s mechanics is the asymmetric distribution of hidden roles and information. Each round, all but one player receives a card with a specific location. The remaining player is given the role of the “spy” and does not know this location. This mechanic creates unilateral competition — in which a subset of players (the spy) fights against a larger superset (the non-spies). As a result, Spyfall is able to create a dynamic where the non-spies must work together to identify the spy while the spy attempts to deduce the location. For example, in the game I played with my friends, I was given the role of a non-spy, which meant that I knew the specified location (“Pirate Ship”), and had to find the spy by questioning other players about the location. Once I believed that a specific player was a non-spy, I worked together with them to find and deceive the spy into thinking that the specified location was not the Pirate Ship. Therefore, the game’s overall objectives directly contribute to its emphasis on social deduction. The non-spies aim to identify the spy or have the spy reveal their ignorance of the location, while the spy seeks to avoid detection and correctly guess the location. These opposing goals create aesthetics of fellowship and challenge as they encourage players to quickly ascertain the roles of the other players in the game and work together toward their specified goal.

Additionally, Spyfall’s open-ended questioning mechanic further enhances the social deduction experience. Players are encouraged to ask questions related to the location, but the game does not restrict the type or content of these questions. This freedom allows for creative and subtle probing, as players attempt to glean information about the other players’ roles without revealing too much about the location. This in turn creates the dynamics of bluffing and strategic communication. For example, in the game I played, I asked, “What’s your favorite dish here?”, to catch the spy off guard. The player who ended up being the spy (Daniel) responded with, “I love the freshly caught fish!” In this case, Daniel had correctly assumed that, due to the abundance of ocean-related locations, they could get away with this answer and deceive the non-spy players. Therefore, this exchange provided Daniel with valuable information about the location while unfortunately making me more certain that Daniel was not the spy. This further exhibits the game’s emphasis on social deduction, as every conversation is an attempt to uncover other players’ roles and gain information.

(The locations chosen for this game of Spyfall.)

Comparing Spyfall to other popular social deduction games, such as Werewolf or Mafia, reveals some key differences that set it apart. In Werewolf and Mafia, players are given fixed roles (e.g., werewolves, villagers, or mafia members) and must eliminate the opposing team through a process of discussion and voting. These games often involve player elimination, which can lead to disengagement and frustration for those who are killed off early. In contrast, Spyfall keeps all players involved throughout the game, as the spy’s identity is not revealed until the end of each round. This design choice promotes a more inclusive and enjoyable experience for all participants. Moreover, the open-ended nature of questioning in Spyfall allows for more nuanced and strategic gameplay compared to the more structured discussions in Werewolf. In Spyfall, players have the freedom to steer the conversation in various directions, probing for information and planting false leads.

Despite its strengths, Spyfall has several flaws. One potential issue is the game’s replayability, as the fixed set of locations may become boring to frequent players. To address this, the game designer could introduce expansion packs with additional locations or implement a mechanism for players to create their own custom locations. This would help maintain the game’s challenge for experienced players.

Another area for improvement lies in balancing the difficulty of the spy role. In some cases, the spy may find it challenging to deduce the location based on the available information, especially if the non-spy players are very tricky in their questioning. To mitigate this, the game designer could consider introducing additional mechanics that provide the spy with more information or opportunities to gather clues. For example, the spy could be allowed to ask a limited number of direct questions to other players or have access to a “hint” card that provides a subtle clue about the location.

In conclusion, Spyfall’s design, which leverages asymmetric information distribution, open-ended questioning, and compelling objectives, clearly emphasizes social deduction-based gameplay. While there is room for improvement in terms of replayability and role balance, Spyfall’s overall game design successfully engages players in strategic information gathering and management in a fun way.