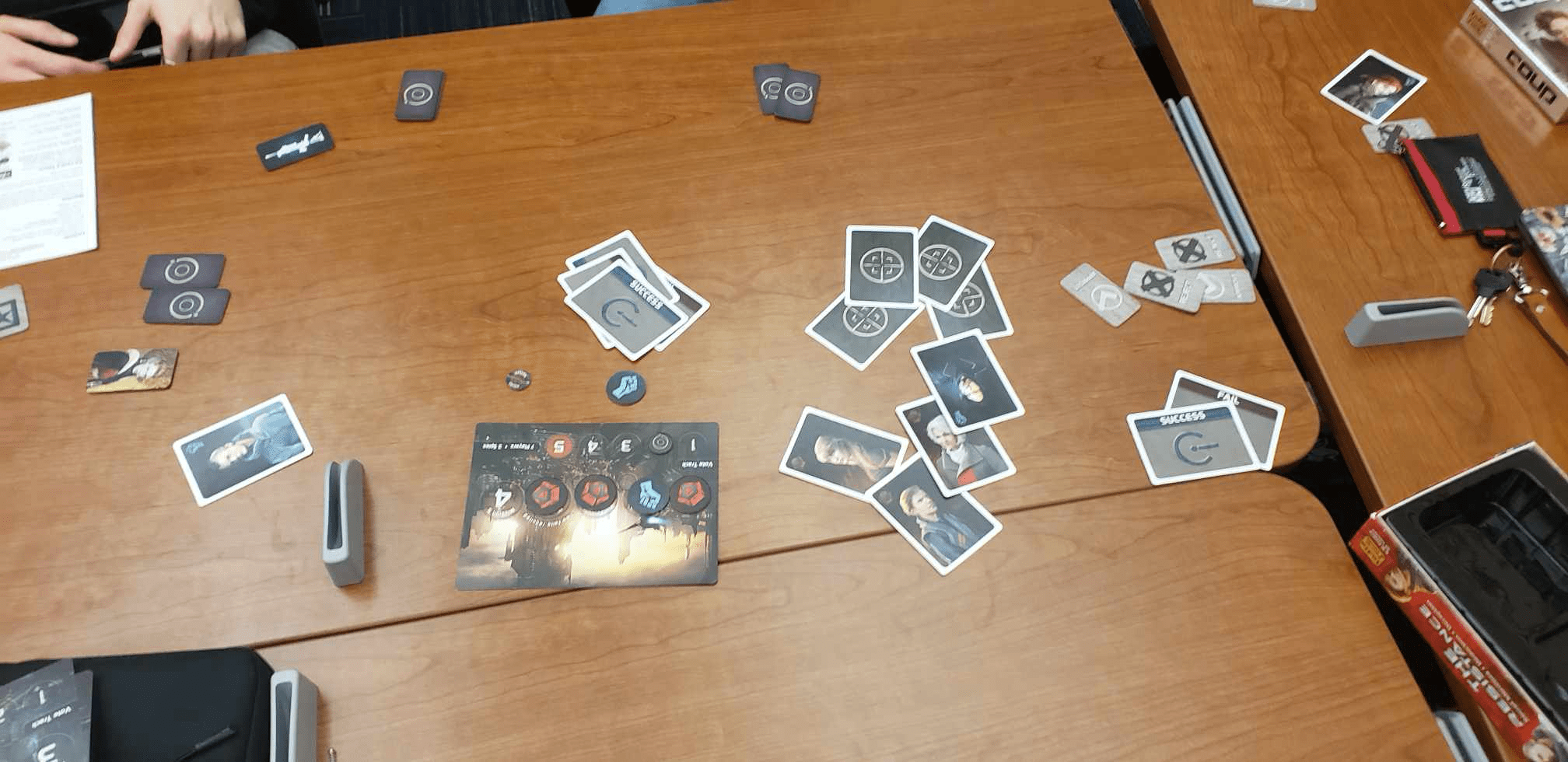

This week, I attended the CS 247G Game Night where my table group had fun playing two games: The Resistance and Coup. For this Critical Play, I’ll focus on The Resistance, although I will draw comparisons to other social deduction games including Coup.

The Resistance is a social deduction game created by game designer Don Eskridge. The game is playable either face-to-face or online on various platforms. Because I was at Game Night, our team played face-to-face in person. The game is designed for five to ten players (we had seven players; there are slight implementation differences depending on the number of players). Because the game is a simple, team-based (although there is asymmetric knowledge of which players are on which teams) party game, its target audience is casual players (likely young adults) looking to have a social but exciting game.

The Resistance emphasizes social deduction through a combination of various democratic mechanics. Prime examples of such mechanics include individual voting (leading to a group outcome), the rule that “players may say anything that they want, at any time,” and leaders serving terms where they choose who to send on a mission, among others.

In practice, individual voting leading to a group outcome means that individual votes are important. Accordingly, it is in the best interest of a player to attempt to convince other players to vote in certain ways. Combined with the rule allowing constant discussion and the rotating leader, this results in a dynamic of impassioned conversations, discussions, and [all in good fun] arguments throughout the game. For example, during our game, two players immediately drew suspicion due to a failed two-player mission. The implications of this two-player mission mechanic and the individual voting on whether to pass the mission mechanic meant that one of those players had to have been on the “bad” team. At first, it was possible just to ignore both players and only look at the other pool of players despite their impassioned pleas. However, after multiple missions within the same game, it became apparent that there was no perfectly “safe” strategy to guarantee passing a mission. At this point, discussion became more heated, and we all got to know each other more. We learned which players already knew each other (a roommate pair, a couple, and previous team members). An example of this was one player’s vote (mechanic) was called out as suspicious (dynamic) by their friend because they allegedly knew some of their “tells.” The friend then had to convince other people, and the discussion helped us talk more. At another point, one player was called out for being overly quiet and therefore suspicious. To deal with this accusation, the player shared some of their insights on who else they thought was suspicious. Ultimately, it was discussions like this that helped lighten the overall nature of the game. The game allowing for and encouraging and talking at all times while people needed to convince others to vote in certain ways helped make sure that conversation was constantly flowing. The game’s dynamic of lively conversation helped cement in my mind the core aesthetic/fun of fellowship throughout. Furthermore, the nature of said conversations (debating, being accusatory/defensive, etc) resulted in the game also having a competitive aesthetic. Together, these two aesthetics (fellowship and competition) demonstrate how the game emphasizes social deduction. Social deduction requires knowing people (fellowship), as well as motivation to figure things out about them (competition). Were the game lacking either of these aesthetics, we would end up with just a social (get to know each other) game or a game that’s solely focused on trying to compete and win, without learning more about others.

As mentioned previously, our group also played Coup at Game Night. Many of us had also previously played Among Us. Arguably, The Resistance does a better job of emphasizing social deduction than Coup and Among Us. This is largely attributable to the differing mechanics of these games ultimately influencing the dynamics and aesthetics. Specifically, Coup is more individualistic as there are no predetermined teams or voting. Compared to The Resistance, in practice, this led to more combative/bullying types of dynamics within the game, which emphasized fellowship less, ultimately leading to an inferior emphasis on social deduction, despite its game category. In Among Us, players only talk (or message, if played online with strangers) during time-limited emergency meetings. In contrast, The Resistance allowing for freeform discussion and incentivizing it via voting and alternating leader mechanics leads to a dynamic of constant discussion, which emphasizes fellowship.

In summary, the specific democratic mechanics of The Resistance enable and incentivize constant personal discussion, which help the game establish strong fellowship and competitive aesthetics, which are necessary for a good social deduction game.