Secret Hitler combines eternally existent fundamentals of probability with internally induced opportunities for deception and behavioral analysis to create a social deduction game different from most in gameplay and aesthetic. In doing so, Secret Hitler approaches social deduction in a unique, engaging manner dominated by neither probabilistic analysis or guessing alone.

Developed by Mike Boxleiter, Tommy Maranges and Mac Schubert, Secret Hitler is officially produced as a physical board game, but shared and adapted versions through any medium—such as online—are permitted for free under its Creative Commons License. Playable with 5-10 players, the game is intended for friends and family of adequate age to make proper deductions (teens/adults). I first played the game online with friends this weekend, following the physical medium’s rulebook. We initially played four rounds with 5 players, before expanding to 7; gameplay and rules vary with player count, resulting in different game balance and player experiences.

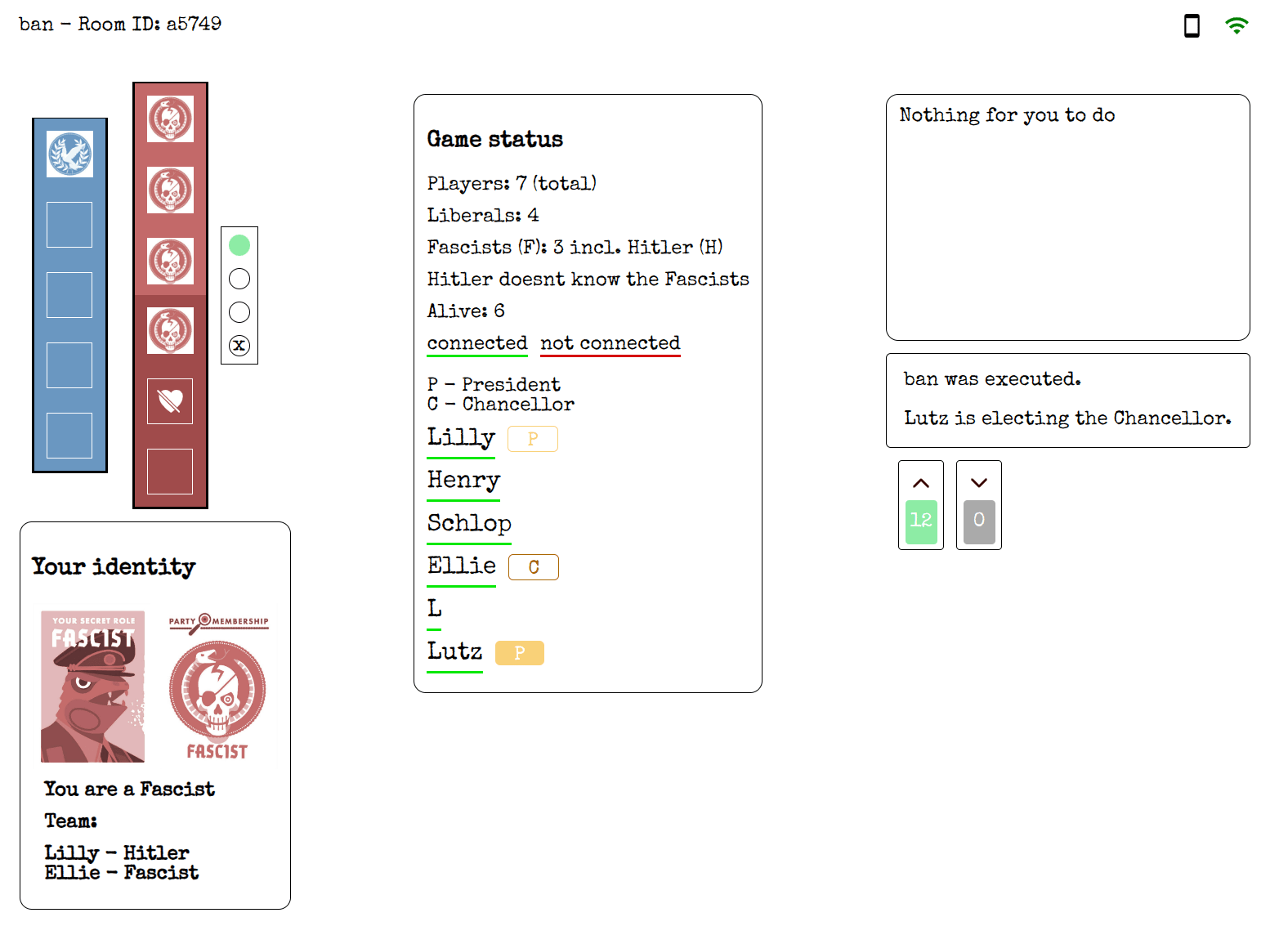

Regardless of player count, the goal of the game is the same: in this zero-sum unilateral competition game, players are divided into two factions: liberal or fascist, with one fascist being “Hitler.” Liberals wish to pass six liberal policies, prevent Hitler from being elected chancellor after passing three fascist policies, and/or assassinate Hitler. Fascists wish to pass five fascist policies or elect Hitler as chancellor after enacting three fascist policies. The known, finite number of policy tiles (6 liberal, 11 fascist) allow for a baseline for player deductions, which gets obfuscated by players’ asymmetrical knowledge upon policy enactment: while the President has complete knowledge of three cards drawn and one discarded, the Chancellor sees only two cards. Other players receive no additional information beyond the card the Chancellor places, and must instead base deductions on prior game events, probabilistic analysis, and other cues such as election votes, and verbal testament. This contributes to the overall objective of outwitting the opposing faction, and a general dynamic of liberal players looking for suspicious behavior, with fascist players trying to blend in.

The conflict of the game derives from the opposing faction and the game’s built-in informational obfuscation. Mechanics such as the voting period, card drawing period, and presidential powers upon enactment of fascist policies help establish the game’s magic circle of slight fantasy political roleplay, enhancing the fun. Although my group played virtually, we followed the official rules from the creators’ website, including silence during card “drawing” and placements, and during voting. In doing so, the game became more intense, realistic, and enjoyable, contributing to each player’s investment in their role.

From my first few rounds, I found that the game had a steep learning curve; we often referred back to the rules to ensure processes were properly followed, which slightly broke the magic circle and roleplaying environment for a few games. Due to this, I found myself relying on external factors, not unique to the game, as basis for my deductions: as a liberal, my primary deductive technique was the combinatorial and probabilistic analysis of policies played versus those remaining. From this external knowledge, I built suspicion on those who disobeyed probabilistic likelihoods. However, that backfired when in our second game, three subsequent elections each had 3 fascist cards drawn, making those involved in said elections seem suspicious, despite lacking control in the manner.

Although an unlikely scenario, I assumed that the low likelihood meant that statistically, at least one of the elections involved a lie, and made (incorrect) deductions from there… liberals did not win that game. In this case, the built-in mechanics of the fascists knowing their teammate was beneficial, since they avoided confusion from those played cards. From there, I adjusted my deduction methods to not as heavily emphasize the probabilistic aspect.

Due in part to massively disproportional knowledge, fascists seemed to have a strict advantage in the 5-player game (winning all 5-player games this session), but the game changed with 7 players, due to Hitler not knowing their fascist allies. This lack of knowledge balanced the game, as Hitler mechanically is closer to a liberal, set apart only by a differing objective. This change in Hitler’s knowledge was showcased when I, as a fascist, was so convincing in my ruse as a liberal that my Hitler assassinated me when they were president.

From the externally existent probabilistic nature of Secret Hitler, to the uniquely-imposed informational obfuscation, Secret Hitler creates a ripe environment for deduction, enhanced further by the general fantasy/roleplay aesthetic. Despite an experienced learning curve, my friends and I quickly became invested in each game, election, and policy enactment. From its accessibility (both in cost and medium) to its general fun, my friends and I will certainly revisit Secret Hitler in the future, particularly with the pain of understanding the rules and strategies slightly alleviated.