Among Us is a truly inclusive game that can be played by anyone, young or old, gamer or non-gamer for the same extraordinary experience of somehow being gaslighted by peers at every round. Among Us is a game developed and published by InnerSloth LLC, available on iOS/Android, PC, VR, and most major gaming consoles (XBOX, PlayStation, Switch). For my critical play, I downloaded and played the game on PC which allowed me to use my keyboard and mouse while also providing me with a larger screen than my phone. This game is unique amongst other standard social deduction games in that it involves minigames with ambiguous ending animations and special transportation methods for specific roles to heighten the experience of trying to find who is among us… Through a combination of deception and exciting gameplay, anyone can enjoy the thrill that emerges from this game.

Although this game could be played by anyone, I believe that the intended audience of this game is kids and teens. From the eye-catching artwork and distinct character design to the low-skill tasks assigned to the players, the game immediately catches a player’s attention and doesn’t push them away with factors like difficulty or complexity.

Unlike other social deduction games, Among Us requires little to no instructions, especially for the tasks, and instead is learned quickest by playing a round or two. Additionally, apart from children and teens, this game could also be seen as targeting any casual gamers who enjoy playing social deduction games, as the skills for the deduction aspect are easily transferable from games like Mafia.

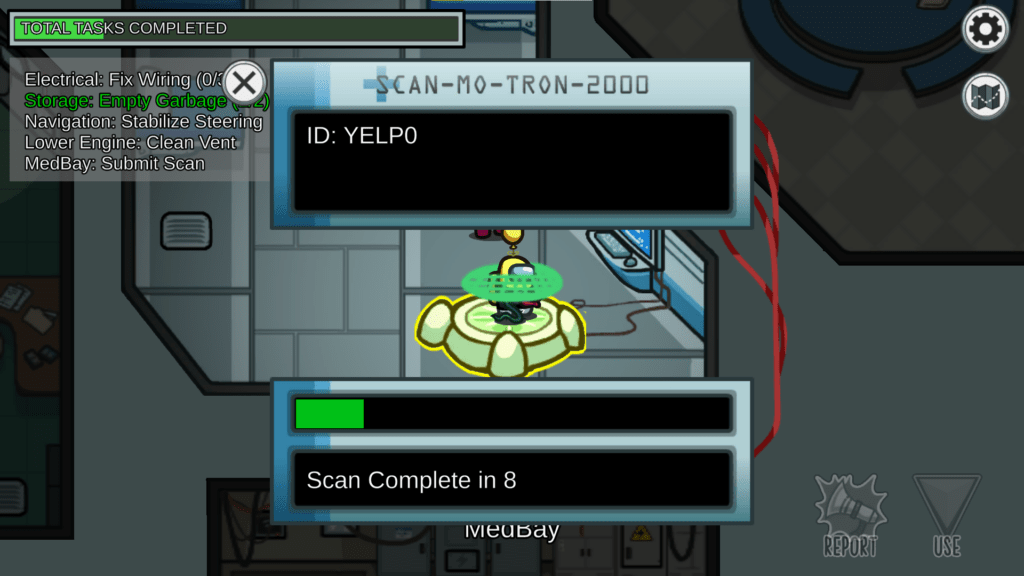

In Among Us, there are a number of notable formal elements which makes this game so unique. First of all, a progress meter is visible at the top of the screen which shows whether tasks are being completed or not.

This means that when a player sees another player at a task station, they can watch to see if the bar actually moves. Another notable aspect of the tasks is that some are visual tasks, meaning that other players can see them doing the task, and others are non-visual tasks, meaning there is no external indication that the task is being performed, meaning that players can effectively “fake” tasks. This means that there are some true indicators built into the game which could remove guilt from a suspect.

The combination of all these elements forms a complex social system in which players must actively deduce and put together pieces to figure out who the impostors are. Using these mechanics, Among Us successfully promotes a game in which players can enjoy primarily sensational and fellowship fun. Players will feel sensational fun because they are constantly under pressure and have to be able to progress knowing someone could jump out of a vent and kill them at any moment. The peak of sensation arises when a crewmate definitively catches an impostor in the act of murder and has to prepare to defend their claim in an intense battle of “he said/she said”. On that note, another important aspect of this game is fellowship. Because crewmates must either successfully find the impostors or complete their tasks, Among Us is a game which depends on players cooperating to a certain extent. If a crewmate trusts no one and spends the whole game running away from other players, they may not complete their tasks in time, resulting in the crew losing due to time. On the other hand, players that are too trusting can serve as an obstacle if they defend other players without solid evidence at each discussion. Although there are definitely aspects of other types of fun involved in this game, such as the brief moments of challenge when the card swipe fails to work, I find that these two best encapsulate the key features of Among Us.

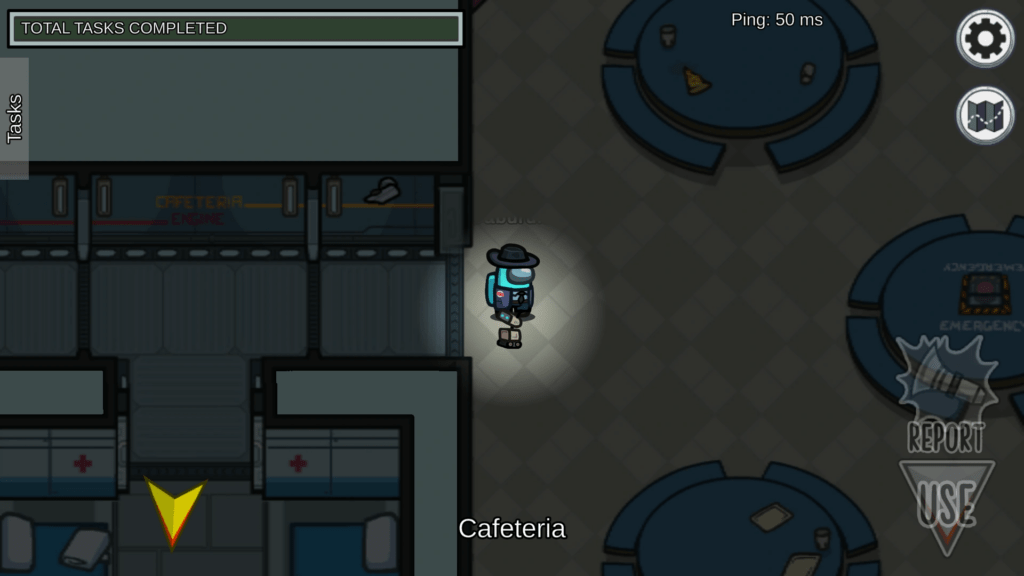

I believe that the designers were able to create these types of fun through a combination of the mechanics, dynamics, and aesthetics. One distinct mechanic of Among Us is the lighting system, in which players can only see exactly what is in their field of view. This means that most of the time, unless in a brightly lit room, players are completing tasks and traversing the map with limited vision.

I see this as not only a mechanical choice, but an aesthetic choice which forces an emotional response from the player that causes stress and anxiety. Since players know that what they see is limited, they are always a bit tense and makes them more on-edge. As for the dynamics, players cannot really divide tasks based on skill level due to the random division, but they can use the simplicity of the tasks to infer conclusions. Since tasks are so easy most of the time, if a player notices another player spending a moment too long on one and then an event happening such as doors closing or oxygen shutting down, they may be able to infer that the person is an impostor who was on their special screen. However, in a similar manner, someone could also honestly just be having trouble with the task itself and will have to be able to defend themselves during the inevitable discussion that follows.

Since all tasks are relatively simple, Among Us is able to highlight the social deduction aspect of the gameplay, taking the focus off of challenging tasks and instead making players focus on what others are doing. As a result, the best impostors are often those with the best improvisations during emergency meetings to explain “what happened”. In order to mod this game for a different experience, I think it would be interesting if anyone dead’s role was always hidden, and dead impostors could perform actions that made it seem as though a crew member was an impostor such as pausing the progress bar or removing the visual feedback from visual tasks. By introducing the aspect of doubt into situations that were previously confident, player’s would have to adapt and trust their own senses more.

During my experience playing Among Us for this critical play, I was faced with several scenarios where people became very paranoid resulting in situations where someone would claim that another player was faking a task, when in reality, it turned out that they were just having trouble moving the wires. Out of the three games that I played, the crewmates won two games with the impostors winning one. In the game that the impostor won, they were able to successfully trick the rest of the group into thinking that someone was lying about the reason they were in a specific room. Since people saw 3 people (2 impostors, 1 crewmate), they were inclined to believe the majority and voted off the wrong person. Then, the impostors were able to kill off enough of the remaining players before forcing a tie vote in the meeting and winning the game.