<<o>> with what eyes <<o>>

You can play the story here, before or after you read the documentation! : )

https://shanaeh.itch.io/with-what-eyes

<<o>> Overview <<o>>

with what eyes is a single-player, interactive speculative fiction set in the future history, fictional Pacific island country of Nusana, which is inspired by cyberpunk, virtual communities, and East meets West urban environments. Nusana is set in the real world, and the characters and social systems are inspired by the often overlooked history of women and minorities in computing. By the year 2048, current trends in natural language generation, social media, brain-computer interfaces, synthetic biology (such as growing human body parts), and various other advancements have led to a confluence of invasive technologies that shape a social context where the concept of “you” and “I” can overlap and merge, such as during full-body experience Streaming. However, access and control over the technologies varies, and advocacy vs. complicity is a constant struggle for those who just want to survive.

Story premise (succinct version)

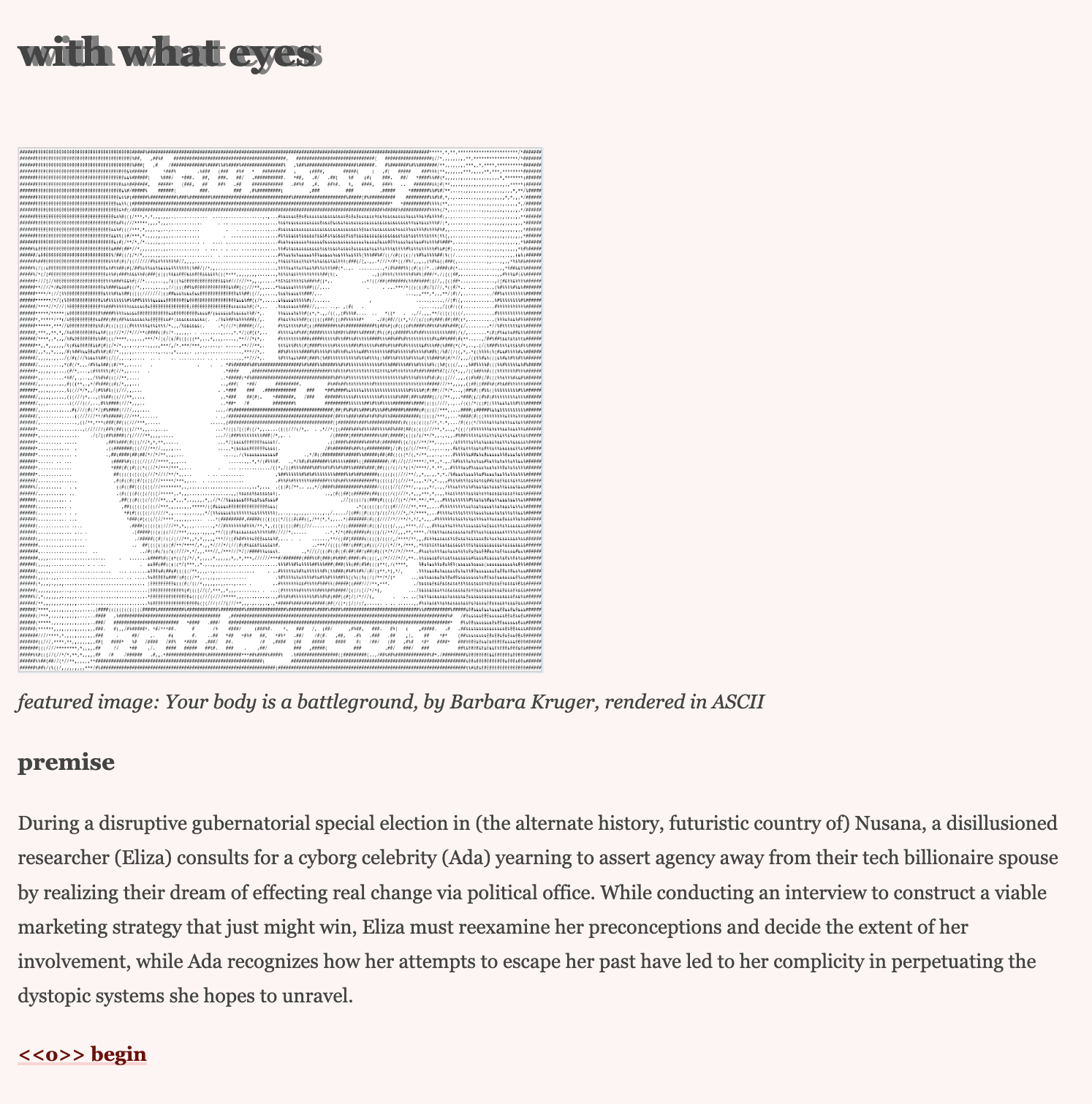

During a disruptive gubernatorial special election in (the alternate history, futuristic country of) Nusana, a disillusioned researcher (Eliza) consults for a cyborg celebrity (Ada) yearning to assert agency away from their tech billionaire spouse by realizing their dream of effecting real change via political office. While conducting an interview to construct a viable marketing strategy that just might win, Eliza must reexamine her preconceptions and decide the extent of her involvement, while Ada recognizes how her attempts to escape her past have led to her complicity in perpetuating the dystopian systems she hopes to unravel.

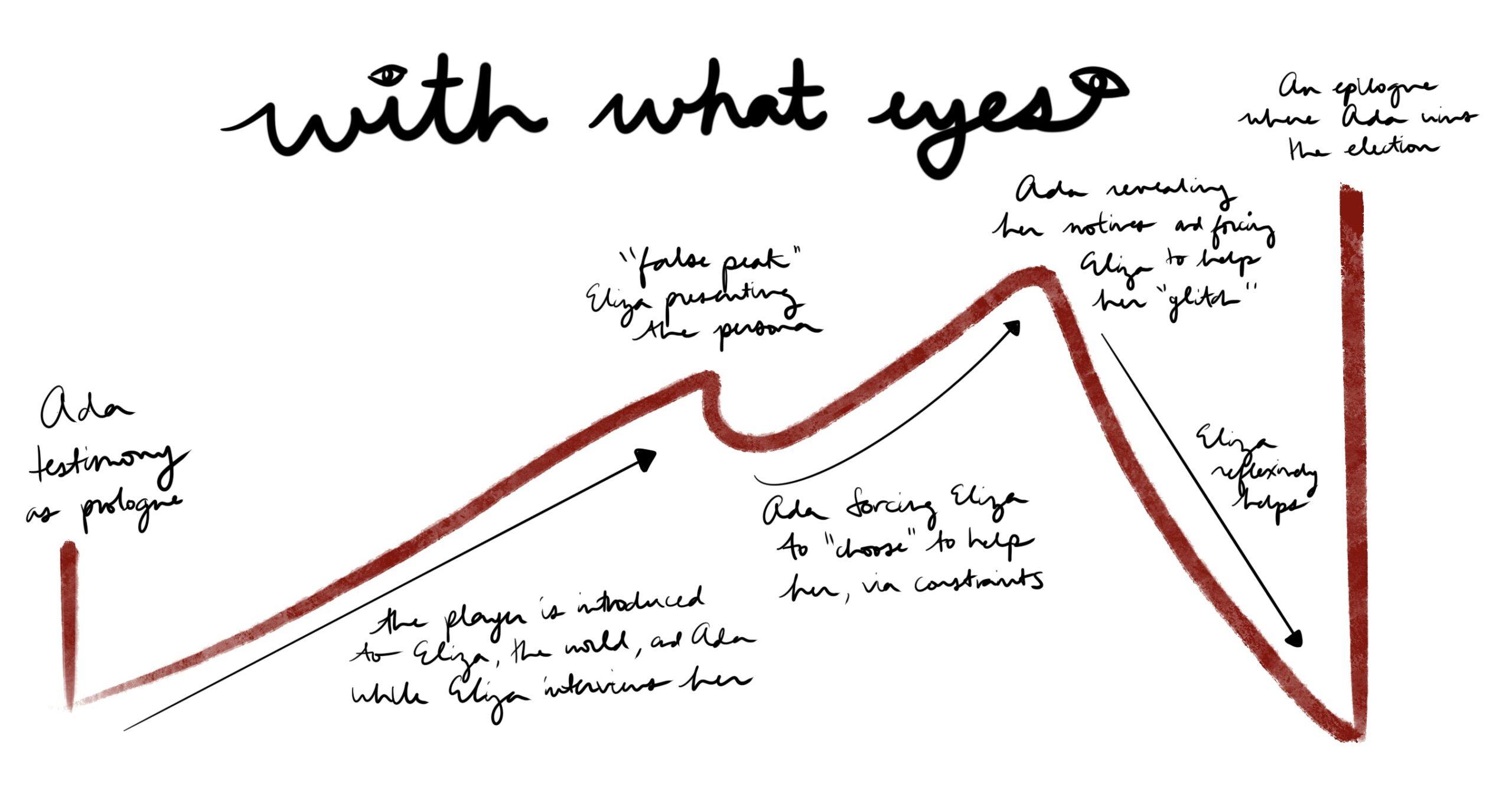

Player journey (spoilers ahead)

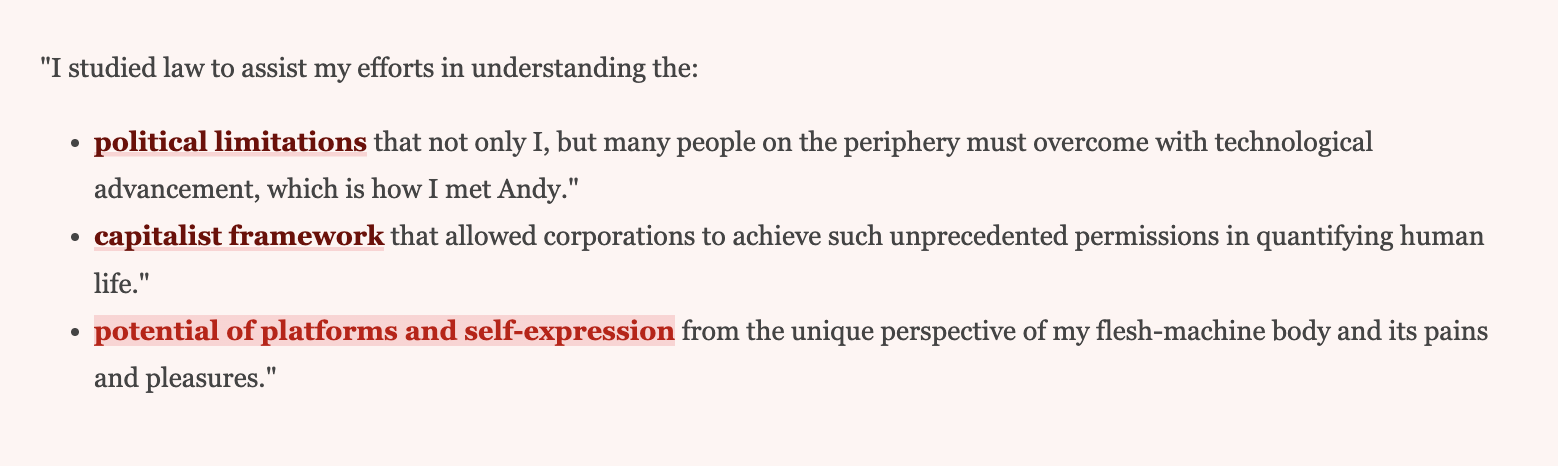

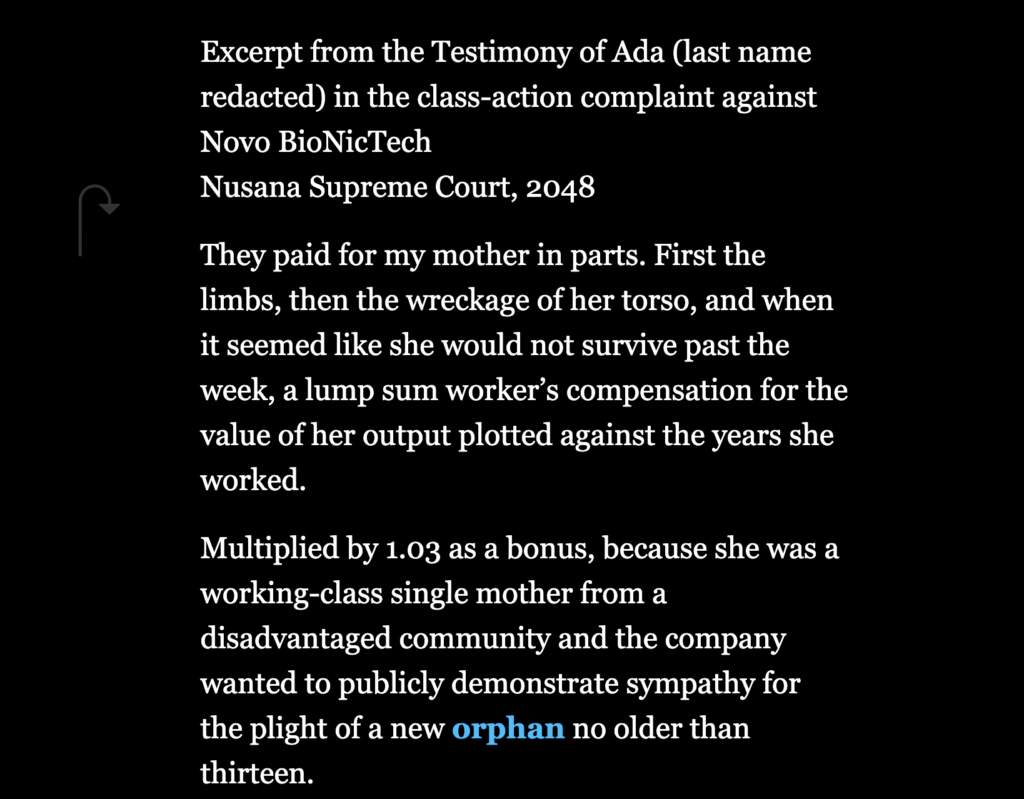

The reader plays as Eliza, a former Silicon Valley worker who helped create InSight Lens (Google Glasses, but can meld directly onto corneas), and then resigned in protest after witnessing how these Lens, in conjunction with NeuroNets (brain implants powered by GPT-16), have reconstructed our understanding of language and perception. Eliza has attempted to hide away from the consequences of her work by returning to Nusana and switching industries to political consulting, but eventually she is summoned by Ada, a fabulous influencer (and lawyer) who wants to run for office to take matters into their own hands. Ada was the subject of an experimental trial that resulted in them losing their mother and having their limbs replaced with mechanical parts at age thirteen, which resulted in substantial bitterness and a desire to make a difference so no one else has to suffer.

This interactive fiction takes place over one interview, where Eliza is a self-effacing, jaded political consultant hired to create a compelling persona for Ada, who had an extended Streaming career but now is shifting tactics for their election campaign. While Eliza is trying to wrangle Ada’s story, Ada has another motive for inviting Eliza. They gradually coerce her to reveal backdoor methods to hotwire the InSight Lens and (temporarily) free Ada from the constraints of the implants that are a constant pressure on Ada’s thoughts and perceptions. Meaningful choices come in the form of “interview questions” and the player’s search for edifying details, along with how the story tracks hidden stats (their interviewing style) that leads to constraints on player agency and choice that reflects the story’s themes.

The two central characters, Eliza and Ada (both named after frameshifting feminine “figures” in computer science history) embody different notions of the “cyborg” as a networked individual of both organic and biomechatronic body parts (including our devices). The relationship between Eliza and Ada begins as a sort of adversarial interview, and by the course of the story, ends with an “understanding” that is nonetheless marred by their traumatic circumstances and coercion that binds them together.

In any case, Donna Haraway would argue the “cyborg” is already each and every one of us today. We are all cyborgs. As Barbara Kruger reminds us, a body — your body — can be its own battleground while you challenge yourself to see yourself in a new light. Or perhaps, you would be aided by new InSight Lens?

<<o>> Context <<o>>

I made this world as part of an ongoing creative project where I hope to examine thorny sociotechnical ethical questions, such as our biases in perception even as we construct personas of others, the dangers of large-scale data mining, the need for corporate oversight especially in fields such as healthcare and biotechnology, and our responsibility as people who will navigate the treacherous waters of “CS + Ethics” again, and again, and again in our professional lives.

Social orders are embedded within and reinforced by technology, disproportionately affecting those on the margins of society, and inequalities in access and technology use-cases have only worsened with the increasing wealth disparity. An innovation that we might initially perceive as value-neutral, such as generative language models or brain implants intended to augment human cognition, may contain implicit assumptions about how we view the purpose of language and for the latter, where we locate “human”-ness in who we are and what we create. I extrapolate from these intersections and current tech trends to speculate on how they might affect not only daily life, but government policy, concluding that the only way forward is through awareness and collective action.

Frankly, unless you have substantial wealth, one of the only ways forward to a utopia is collective action. Whether we plunge headfirst into new technologies while inventing the future, or keep our heads afloat and work for the paycheck, we have the responsibility as designers, developers, and citizens to create the world in which we (and our descendants) want to not just live, but thrive. This could take the form of engaging in ethical discussions at the workplace, raising awareness through art and advocacy, and good, old-fashioned voting and talking to your elected officials for as long as we live in a form of democracy.

Besides contacting your U.S. elected officials (https://www.house.gov/representatives/find-your-representative, https://www.senate.gov/senators/senators-contact.htm) and giving them passionate, handwritten letters about your thoughts and feelings about how they should vote, I also invite you to peruse the following resources (below in the “appendix”!) that personally have been very helpful for understanding these issues of technological and social change. : )

<<o>> Learning objectives <<o>>

Overall, while reading and playing this body of text (select all!):

Overall, while reading and playing this body of text (select all!):

- I hope the experience makes you aware of the “clothes” (identities and assumptions) you are wearing, and the subjective media-influenced world that you inhabit every day.

- I hope the centering of the narrative on currently underrepresented queer and feminine figures, and their dystopian circumstances, help you critically and empathetically look at existing parallels of forcing narratives onto others in our modern-day.

- I hope you ask yourself the question “with what eyes // do we claim to see?”

- I hope that “you hope,” because ultimately, I think dystopias fundamentally believe in the positive trajectory of humanity and warn us of the dangers so we can focus on making utopias.

<<o>> Iterations <<o>>

I had a total of 8.5 playtests, 4.5 external, 4 in-class, 6 M, 3 F, most in their early twenties. I wanted to practice sharing my written work with others, and experiment with a new writing process where I truly start at the “embarrassing” paper prototype and keep building onto the story shape until it becomes a gorgeous sculpture!

Besides the in-class playtests, I tried to treat this project as an opportunity to reach out to people who had deep interests or specialties in the related topic, such as a friend who is a journalist / lawyer-in-training, and a creative writing professor. I also ran an audio-only playtest to mimic an interview style more closely. (Note: For external playtesters not pictured, I can show photos on request, but as a general principle I try not to publicly show names or faces to somewhat anonymize the data.)

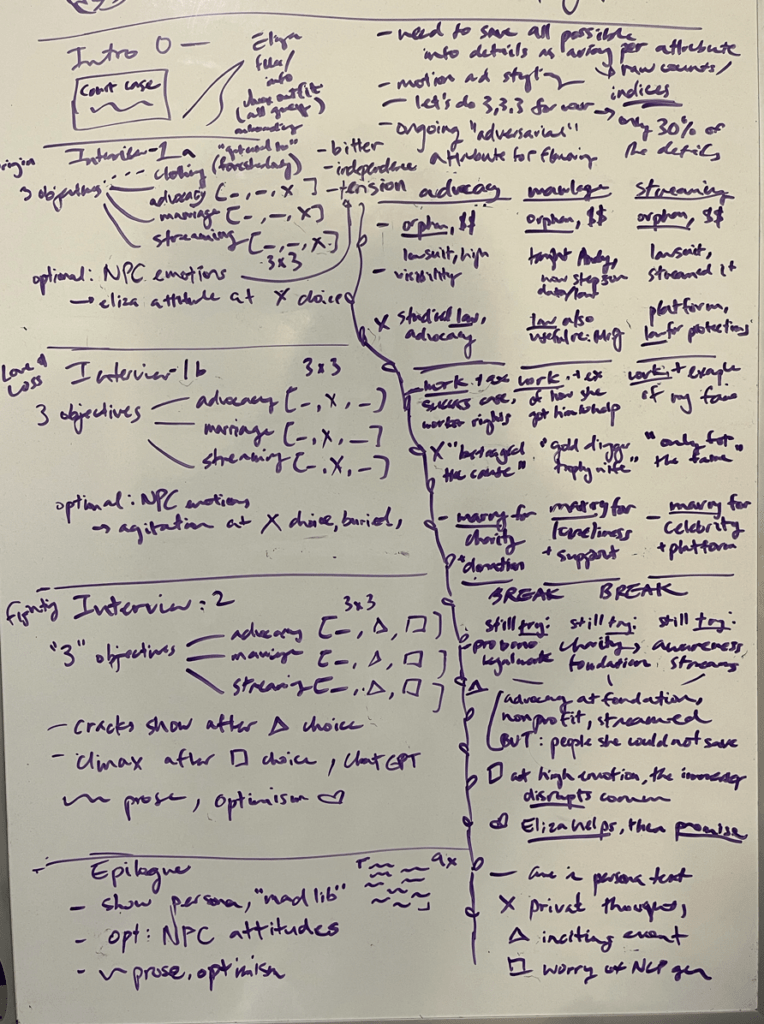

Overall, the core idea remained the same: the two central characters Eliza and Ada engaging in an adversarial interview, until backstories and motives come to light through player questions and story responses, within the context of the dystopian world. The story expanded from ~8 paper questions to ~6500 words, with 65 passages, not including hidden variable conditionals.

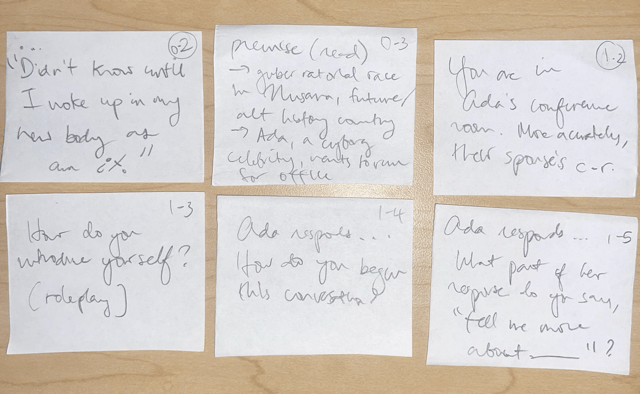

Version 0 (class 4b: will a parser prove true? no)

This version was an explanation of the premise and a few questions for the start of the interview, written on paper flashcards and with my DM’s readiness to “theater of mind” the roleplay for an interview between Eliza and Ada. At the time, I thought this story could take the form of a parser, and as I already had substantial work on the premise and ending, I focused on interaction design.

In this playtest (4B, in-class), I tested a “paper, plus theater of mind prototype” on a classmate (M, early twenties), who was immediately plunged into the role of interviewing as Eliza while I played as Ada. Some valuable feedback I received include:

- the premise was interesting and the characters Eliza and Ada seemed distinguishable given the discrepancy in their dress (gray-black clothes vs. a couture red gown).

- the interview format would be a great way to slowly reveal information.

- the parser format was daunting and might not lead to the one ending that I considered to be “true.”

Version 1 (week 4 in-between: onto meaningful, sensitive storycraft)

I shifted toward a linear story, which first meant writing ~3000 words with the key scenes with emphasis on the prose and relationship between Eliza and Ada. I ran two external playtests, one first with a student journalist / lawyer (F, early twenties), and another with a student writer (F, early twenties). The two playtesters read this draft from beginning to end, along with a quick run-through of the first few passages on Twine, Harlowe.

Some valuable feedback I received, and the changes I made as a result, include:

- the relationship between Ada and Eliza was “functional” but rather stale, as Ada seemed too approachable and transparent about their desires from the start, which made Eliza’s hesitations and Ada’s backstory seem inconsistent. The worldbuilding was “very interesting” and “reflects the themes very well,” and they wanted more incorporation of the details into the story.

- I decided to research adversarial interviews and consider reframing this interaction (and the characters) as characters “interviewing each other” but having hidden questions and probing that are revealed throughout the story.

- Reflect further on the contexts where the characters might identify more as “human” or “other,” especially as it relates to their machine and cyborg components, and to incorporate more nuance into the negative and positive connotations.

- I rewrote the interactive “choose Ada’s backstory” section with more variation, and incorporate more grounding details for Eliza.

Version 2 (class 5a: Twine x Harlowe, for a “functional” beginning)

I finished a draft of the story and brought it onto Twine (Harlowe), which essentially meant black screen with white text and hyperlinks, and I ran a playtest in-class on a student (F, early twenties).

This playtest was most useful for testing how a reader would experience the story through Twine formatting, with broken-up text and readers having to click through the sections. The playtest lasted 20 minutes, with comments on how the material was engaging, albeit long, and there was a dearth of interactive choices… Hence, I went back to the drawing board!

Version 3 (class 5b: meaningful choices)

I wrote an additional section embedded in the then mostly linear narrative, which included more meaningful choices about choosing Ada’s “backstory.” Story “pearls” were essentially the same until the end, except for hidden variable trackers that would change the story at the very last few segments.

I first ran a playtest in-class on a student (F, early twenties), which took approximately 20 minutes, with a few speed-throughs for the text-heavy sections. Some valuable feedback I received, and the changes I made as a result, include:

- the choices while selecting Ada’s backstory (“I pursued advocacy” first, and then met “an older cyborg”) were interesting at first, but then “are these really all different stories — did I read all of that for nothing?”

- While I wanted to reveal at the end that all these story threads were true (and people are complex individuals but an interview might not reveal all the facets), I had to get myself out of my head and into the player’s perspective, who would see a largely unchanged story / game state until the end.

- I had to make the choices feel meaningful at first — as in, shape the conversation — before constraining the choices, for additional emotional payoff.

- bug test the linking and story details for consistency, such as distinguishing the switch from Ada’s voice at the first page to Eliza for the rest, and putting their dialogue in quotes with explicitly, “she said.” Likewise, there was confusion about the “Lens” and ubiquity of the technology, as while it felt like an “intriguing, complete and thorough world,” the playtester was not sure why Ada was such an anomaly in this context, which the viewpoint character Eliza should have known.

I also discussed with Christina about how I was facing the challenge of having a linear, author-led story that did not offer much in the way of meaningful choices. She suggested that I consider the different ways a conversation might unfold as different ways to get to the “same” ending. This helped me incorporate an additional underlying interview (Ada asking Eliza probing questions), and potential decision points where Eliza must switch strategies at a certain point to get to the “right” ending.

Version 3.5 (week 5 in-between: adversarial interviewing)

I then ran an audio-only playtest on a young professional (F, early twenties) to mimic an interview context, without the Twine screen as a mediator. We got through the whole story, albeit with some abbreviated descriptions for the text-heavy sections, and they provided great feedback and suggestions:

- consider tying in backstory more naturally into the different decisions Eliza can make, and try to make it more personal, especially considering the “pivotal traumas that people have, what makes us different as people is how we respond to trauma.”

- affirming a design brainstorm where I gather certain player variables, and then explicitly mark in the text which decisions they cannot select due to their prior choice, furthering the learning outcome of constrained choices.

- in a future iteration, have the interview responses incorporate stereotypes that people in the story would have about cyborgs, so the players have the option to choose a more “calculated” path that is the “best choice for my career” and how it might reflect a computerized, overly optimized mindset.

Version 4 (class 6a: more custom CSS and “experimental webtext”)

After the 6 playtests, I revised my story text and played through the Twine story a few times, and although only Harlowe has the “click to make text appear on the same screen” feature, I decided to switch over to SugarCube for more custom CSS and long-term customization potential.

I ran a “mostly complete” playtest in-class on a student (F, early twenties), which took approximately 23 minutes with some text speed-through. Some valuable feedback I received, and the changes I made as a result, include:

- the playtester felt like they were leading the conversation (which meets my design goal), but unsure of their motivation to get these decisions.

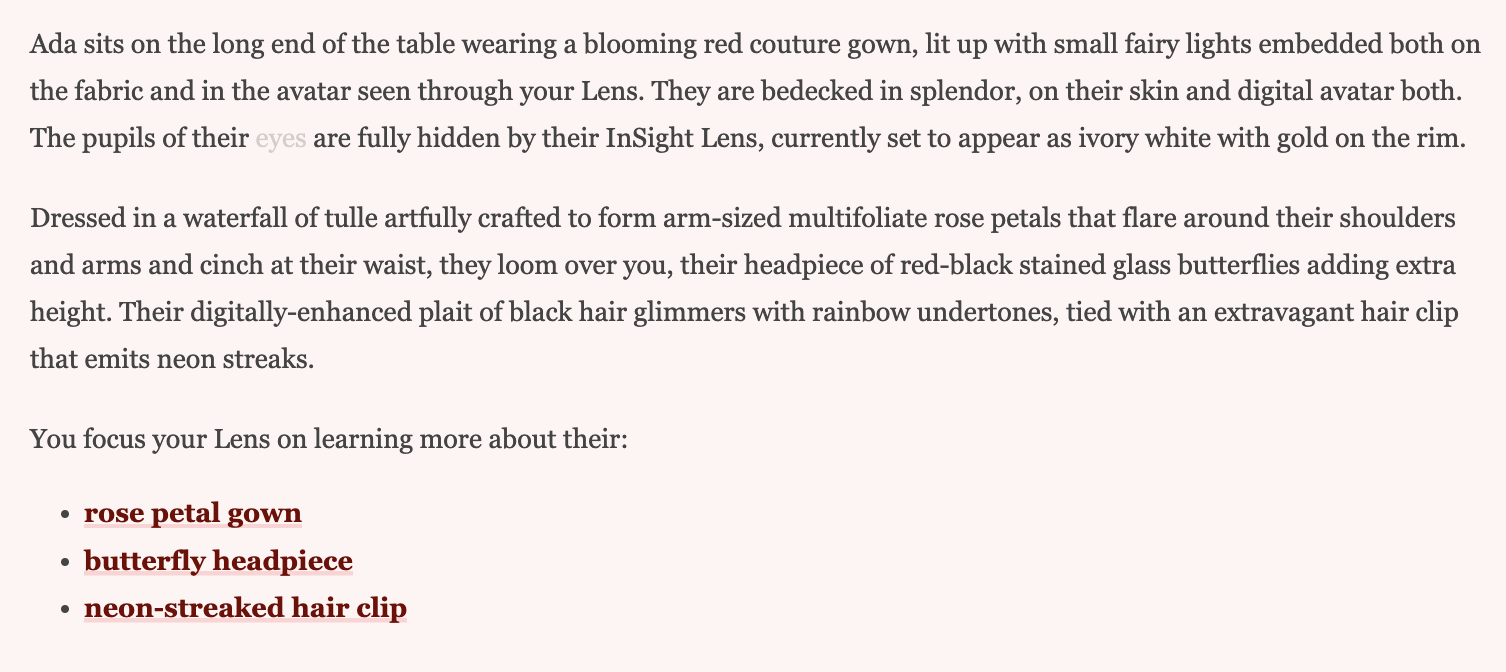

- They also affirmed the importance of text callbacks, such as the player selecting to focus on the “neon hair clip” and how it comes up again later in the story.

- while they were “immersed and engaged,” and noted that “the writing is doing a lot of work here,” and that it “got pretty intense,” it was rather text-heavy and they would expect to see their choices coming back more, and they noted a few bugs to fix.

- I reflected on the linear-ish conversation style, and ultimately decided that I would keep this piece more on the side of “experimental webtext” rather than choice-based interactive fiction, to stay consistent with my overall worldbuilding.

Version 4.5 (class 6b: more custom CSS and revisions)

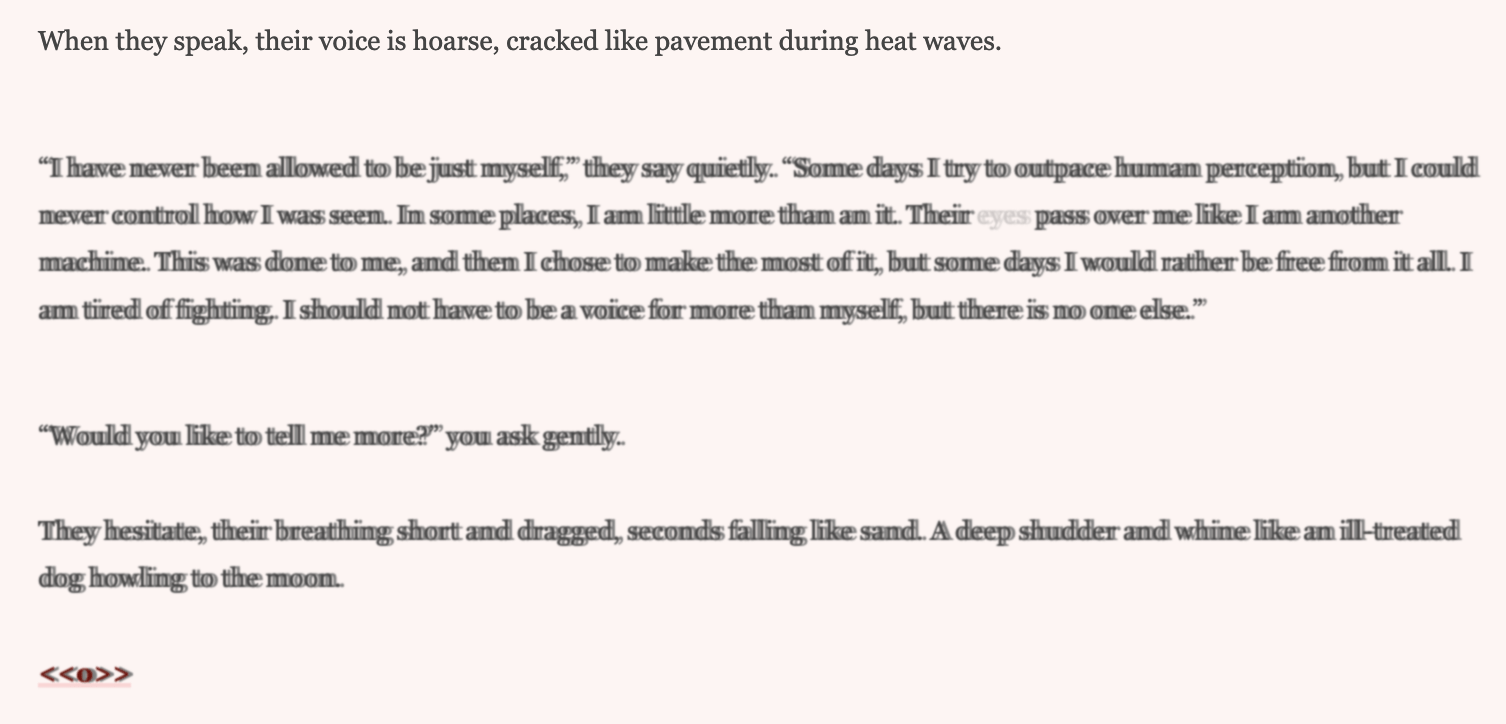

In between 6a and 6b, I paid special attention to refining the text and incorporating more CSS elements, such as “glitchy text,” “highlights,” and “blinking” for the word “eyes” to have a subtle feeling of the player being watched. I consulted an English department creative writing professor (M, experienced) which I count as a 0.5 playtest by showing them excerpts for their feedback on the storycraft, and I also ran another playtest (M, early twenties) of the fuller CSS-augmented experience.

Some valuable feedback I received include:

- overall, this was a cohesive world where they both felt like there was more story and connections (which there is — my thesis!). The professor noted that for additional layering, I could write other stories that explore the larger value system of my main character Eliza, such as their work in futuristic Silicon Valley, for “an origin story of a quality or tendency.”

- the characters felt fully fleshed-out, and while Eliza’s backstory was sparse at the start of the story, it was gradually revealed over time. One playtester joked, “Is Ada about to kill me?” so the “adversarial interviewee” angle really came out!

- they both noted that the writing felt formal, almost computerized, which was intentional (especially with the second-person alienation), and the playtester thought the CSS, especially the glitchy text, added additional depth.

- they both gave some accurate nitpicks about minor inconsistencies, such as why “no one else can do it” (had to make Eliza’s special circumstances more clear), which I then tweaked.

Given the looming deadline, I focused my remaining time on documentation and refinement.

Version 5 (refined and ready)

The final-ish version below!

<<o>> Play the story here! <<o>>

https://shanaeh.itch.io/with-what-eyes

With ~6500 words, and ~65 passages, this character- and worldbuilding-heavy story is truly a “text environment in which to think” (Bret Victor). The story expanded from ~8 paper questions to this behemoth, not including hidden variable conditionals.

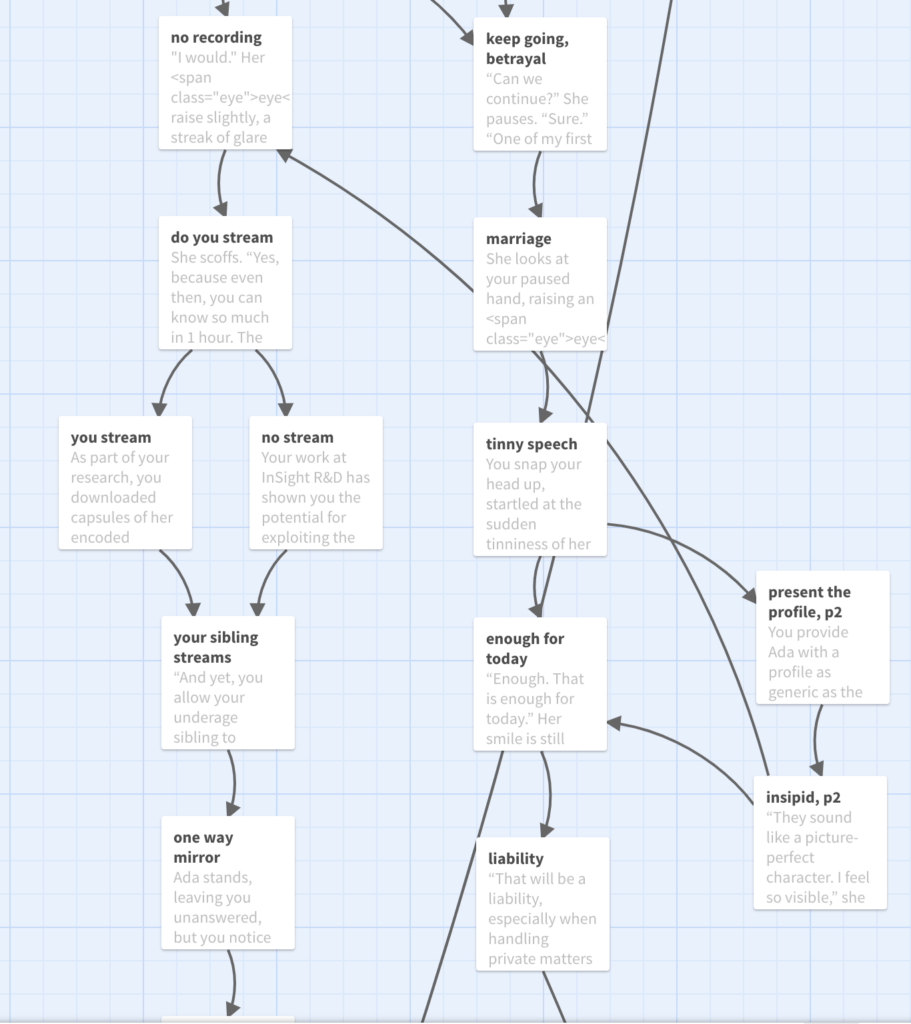

Twine map (gif)

Note: there is hidden logic in several passages in which only certain bits of information are revealed, depending on variables such as “observation” and which details are chosen earlier.

Meaningful choices and design decisions

I already discuss some of this above in the overview section, but I want to explicitly call out these four details:

- The player, as Eliza, seems to “select Ada’s backstory” as part of the interview process and constructing a persona, and Ada will reveal additional story details if the player chooses sections with one of Ada’s family members named. At a decision point where Eliza shows “what she has so far,” the interview must continue longer if the player has not “unlocked” at least one story, such as how Ada first met her husband. In various UX research interview tips, we are encouraged to get our interviewees to tell stories and push on “telling details,” such as names and particularly vivid descriptions, which shaped the nature of some of the options.

- At other (different) passages, one of Eliza’s choices is visibly crossed off based on Ada’s questions about their interview style and approach to assessing people. Even as Eliza is assessing Ada, Ada is also assessing her, a reminder of our visibility especially as designers, user researchers, and people.

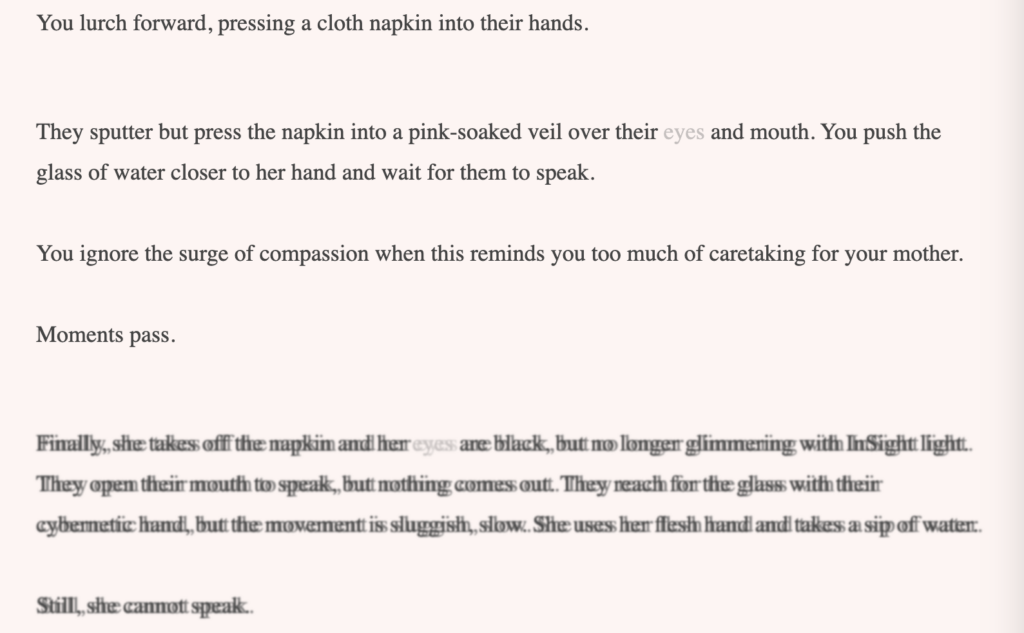

- Continuing on the “illusion of choice,” Eliza seems to have several choices when selecting her motivation for doing this interview and for Ada’s speech, but when they are clicked, it is revealed that all the choices are “true” and there is no “less worse” option. And yes, given the namesake Eliza as an early NLP program, at the climax of the story, Ada has a line directly from ChatGPT (in a future iteration, I would link this up to the GPT-3 API directly). The two images below contrast Eliza’s fixed circumstances (she took this job out of responsibility to her family) along with Ada’s constraints with a NeuroNet implant pushing at her thoughts (if she does not resist, her brain chip speaks for her).

- I am currently really fascinated by concepts of biased perception, information manipulation, persona construction, and controlling one’s “image,” and the central idea about this work is how Eliza and Ada’s views of each other forcefully change over time. Within the constraints of text-only CSS and still making the story “static” enough to read, I used <<o>> as the “next” marker, have every instance of “eye” slowly changing in opacity over time (~30), have the first paragraph in passages with player questions “blink,” and eventually apply a “dizzy glitch” effect for the climactic section. My overall color scheme is for different levels of “red” visibility and bleeding out (vulnerability level: show the world you bleed just as much as anyone else), which becomes relevant by the end. I also selected a more traditionally feminine color palette (red and pink) to relate back to the theme.

<<o>> Reflection <<o>>

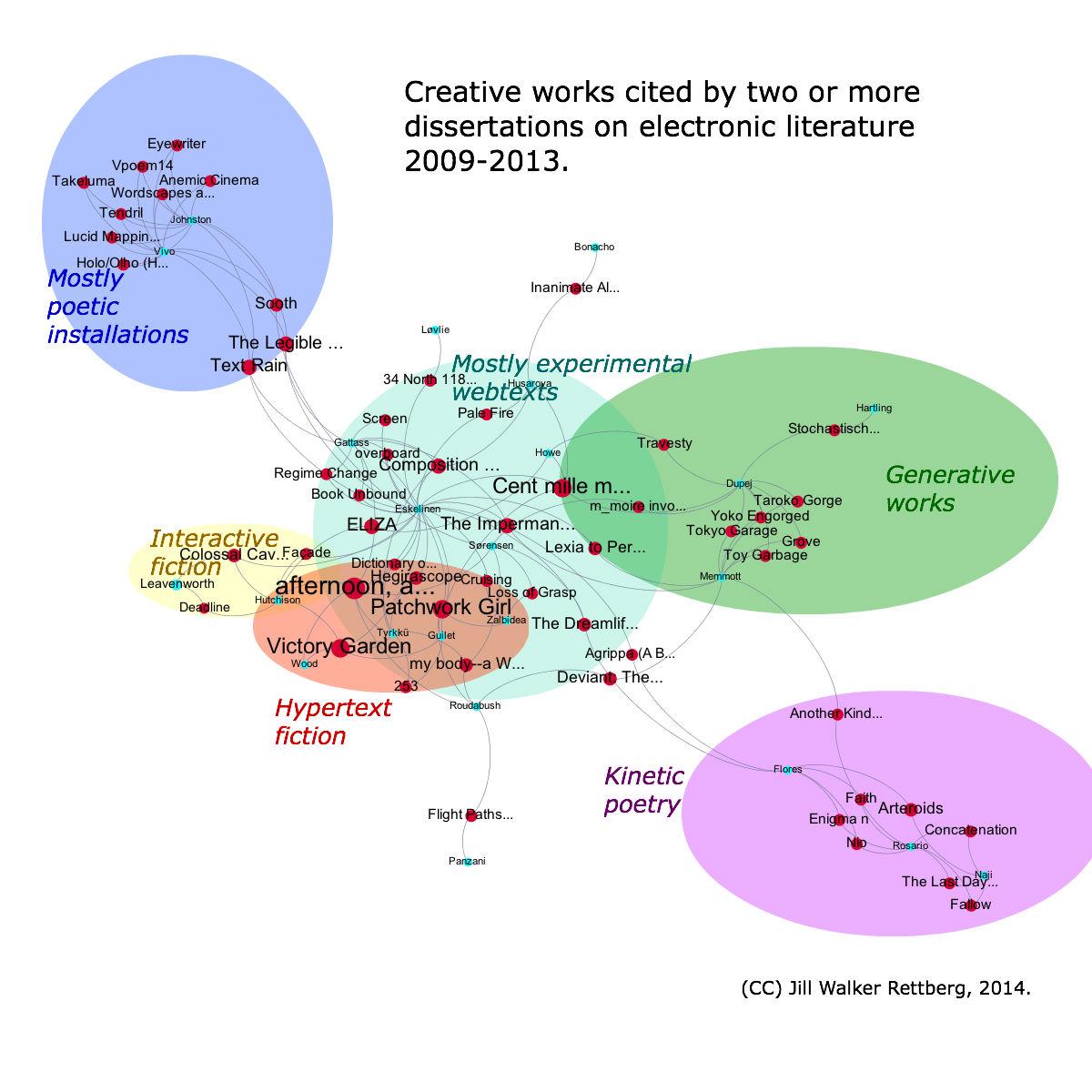

No reflection is complete without consulting additional literature. : ) I view this project with what eyes as a cross between “experimental webtext and interactive fiction.” http://electronicbookreview.com/essay/visualising-networks-of-electronic-literature-dissertations-and-the-creative-works-they-cite/

Overall, I set out to explore a futuristic world where I could explore several “CS + Ethics” questions from within a story, test out a “prequel” version of an extended creative project featuring Eliza and Ada with my learning outcomes, and also brush up on CSS and interactive fiction game design. I am grateful for my playtesters who said they were immersed in the world, invested in the central characters, and engaged in the experience, because this is a great signal that I should return to my thesis and perhaps share it with the world! Or, write other relevant stories! (Or, perhaps both choices are true!) I continue to believe that dystopian worlds are excellent critiques for our modern society and can help us envision more successful ways forward to a utopia, and this belief was only affirmed by creating this piece and hearing my playtesters find parallels to our modern day, like GPT-16, NeuroNet implants, and other technobabble that I directly reference from modern innovations that strike fear (curiosity) — surprise (sophia) — and eventually, insight.

I am more experienced in story writing than game design, which meant that I started this project with a really strong conception of how I want this story to unfold, along with the writing style. Thus, I wanted to grow further by building interactions that were 1) meaningful to the story and 2) felt meaningful to the player, which are two different things ~ “seeming is not being”! I had hidden variable tracking player decisions and sections with callbacks, but I learned to break up text in certain sections, add some CSS flavor, and explicitly show the readers the effects of their choices as much as possible, even if were as simple as “what detail did you notice first,” to keep readers engaged beyond the strength of the story. For what it’s worth, I think this story is more on the side of an “experimental webtext” than an “interactive fiction” (see image), but as Christina has noted, game design is a term more akin to a “centered text” than a ”bounded set.” While I had tried to keep passages short, and in general write as succinctly as possible to get the main story arc across, considering that the supposedly short story is almost a novelette at ~6500 words, and this documentation is verging onto ~4000 words, I wonder if I should accept thoroughness as a personality trait and just continue writing as I desire. In a future version of this project, I would like to convert this Twine piece into a custom HTML5 webtext experience that verges on journalistic article, but as part of that, I would also like to build a reusable engine for future projects… which I began, but will take more time.

In the future, I will continue working on this project because this universe is an ongoing effort of several years now, but also, this project was a great prototype for me to test and grow my story writing and game design skills, and to remember to prototype early and often! I notice that my processes for (product) design, art and writing, and general life are starting to converge, but I am accepting that this is only because I am improving as a Shana (who views “interdisciplinary design” as a centered set where I can frankly borrow methodologies across fields). Younger me had this conception of a writer as someone who works only with “pure text” on a document, and while I continue to start almost every project on paper (and it seems that Matt Leacock does as well), I have evolved so that I incorporate other elements like mind-mapping and concept modeling, RITE-style iteration (while retaining my design vision), and also accepting that projects that I care about deeply will just consume the majority of my time and attention, and to plan accordingly and find fun in the process. Making with what eyes was a joyful experience!

Thank you for playing! : )

<<o>> Afterword <<o>>

I also include an afterword within the Twine story that includes some deeper dives of the core topics, along with some relevant stories I recommend!

I am particularly fond of how the hyperlinks look with the CSS styling!

Topic deeper dives

- Cory Doctorow’s essay, “How to Destroy Surveillance Capitalism” : https://onezero.medium.com/how-to-destroy-surveillance-capitalism-8135e6744d59

- Donna Haraway’s essay “A Cyborg Manifesto,” an essay about how we are already cyborgs, with discussion here: https://www.wired.com/1997/02/ffharaway/

- GDPR (Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation) vs. CCPA (California Consumer Privacy Act) https://fpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/GDPR_CCPA_Comparison-Guide.pdf

- Gilad Edelman’s Wired article, “Why Don’t We Just Ban Targeted Advertising?” https://www.wired.com/story/why-dont-we-just-ban-targeted-advertising/

- OpenAI’s ChatGPT, as a novel technology that will disrupt constructed language as we currently know it, https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt/

- Stephanie Kwolek, who researched and discovered Kevlar for DuPont, who owns the patent, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephanie_Kwolek

- Joseph Weizenbaum’s ELIZA, an early conversational natural language processing program, and the protagonist’s namesake, https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/365153.365168

- The “ENIAC Girls,” the first computer programmers, who were women https://www.army.mil/article/98817/womens_history_month_eniac_first_computer_programmers

Relevant stories recommended

- Aliette de Bodard’s short story, “Immersion” https://clarkesworldmagazine.com/debodard_06_12/

- Jennifer Egan’s Twitterfic short story, “Black Box” https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/06/04/black-box

- Ken Liu’s short story, “Good Hunting” http://strangehorizons.com/fiction/good-hunting-part-1-of-2/

- Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Ones_Who_Walk_Away_from_Omelas

- NK Jemisin’s short story, “The Ones Who Stay and Fight” https://www.lightspeedmagazine.com/fiction/the-ones-who-stay-and-fight/

- The Pudding’s GPT-powered article “Nothing Breaks Like AI Heart” https://pudding.cool/2021/03/love-and-ai/

- Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frankenstein

More about the extended universe of my project here! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J9c7pTi0RqY

Thank you again for reading! : )

Shana’s game places the reader right in the thick of a very fleshed out world inhabited by characters with detailed backstories. It felt really important to notice every word and pixel of the experience. After reading Shana’s write up I realized there were many details I missed, like the ChatGPT line and the crossed out choices. Shana used the Twine medium well in this respect with the colors and opacity. This was a carefully constructed immersive experience that requires multiple playthroughs. Paying close attention rewards the reader. Even though this may not have been the explicit intention, the experience of reading the story is in itself a practice for awareness and examination about the world around us. Overall, Shana did an incredible job communicating the values of sociotechnical ethics and the need to closely examine embedded values in technical innovation. Shana took a very complex multi-faceted values and created a simple setup that communicates those values without simplifying them. The setup being a cyborg and political consultant in an interview. I think it’s brilliant to place these two characters in an interview, an interview a place where every word choice and presentation matters. I really liked that the questions that Eliza chooses impacts what you hear from Ada and mirrors real-world interview situations.

I think given the time frame we had, this interactive fiction was packed densely. I wonder how another iteration might look with these tightly woven details more spread out. In the beginning it does take a lot to get situated. I think reading the documentation to get more of the backstory helped with following the storyline.

I cannot overstate how much I loved this game. The prose was so beautiful and visceral, the formatting so deliberately considered, the worldbuilding so rich — I’m in awe that this was written in such a short timeframe. I was one of the early playtesters for this game (when it was still in Google Doc form) and was already excited for it based on the snippets I got to preview, but the final version blew away my expectations.

While the story was fairly linear, I believe it used the IF medium effectively to play with agency and futility in order to create a particular emotional arc that would have been difficult to achieve in a non-interactive medium. At first, it bothered me that my choices during the interview did not seem to matter, particularly those which dealt with Ada’s backstory; during my playtest, I brought up that it felt strange to be allowed to choose Ada’s backstory and motivations, as it felt at-odds the story’s intent to discourage me from drowning out Ada’s voice and speaking on her behalf, and this feeling persisted when playing the final version. However, that changed once I reached the point where the game starts taking away Eliza’s choices; at that point, the narration begins confirming that, in every case where the player was asked to choose from a list of motivations or backstory elements, all of the choices were actually true all along, and the player was merely choosing which to acknowledge. This reframed my understanding of those previous choices and led me to appreciate the purpose they served — to instill an understanding that, although we may pick and choose which elements of ourselves and others to acknowledge, that doesn’t make the hidden elements disappear, and we must be careful when attempting to tell others’ stories for them because there is always more that we don’t know. (At least, this was my takeaway.)

I adored the way language and formatting were used throughout the story — the highlighting of the word “eyes” to draw uneasy attention to the presence of the characters’ Lenses, the redacted choices to give the player a taste of what could have been, the brief but poignant use of “it” to refer to the malfunctioning Ada as the deactivation of their Lens causes a meltdown. The adversarial interview style was an interesting way to pace exposition delivery, and the slow understanding built between two characters who at first appeared to be opposites made for a satisfying emotional arc.

If I had to offer criticism, it would be that in my first playthrough, when I reached what I assume to be the bad (or at least not-true) ending (where the interview is cut short and Ada never reveals her true intentions), it wasn’t clear to me why my choices had led to that ending. Assuming that the intent behind the story was to discourage me from speaking for Ada and encourage skepticism of the technology, I had tried to choose all of the choices which allowed Ada to speak for herself rather than discreetly verifying her information with my Lens. However, this led her to refuse to open up to me, which was the opposite of what I expected. It could be that I misunderstood the message or the intended implications of these choices, so I think making the reason for this outcome clearer would help the player to more effectively achieve the learning goal.