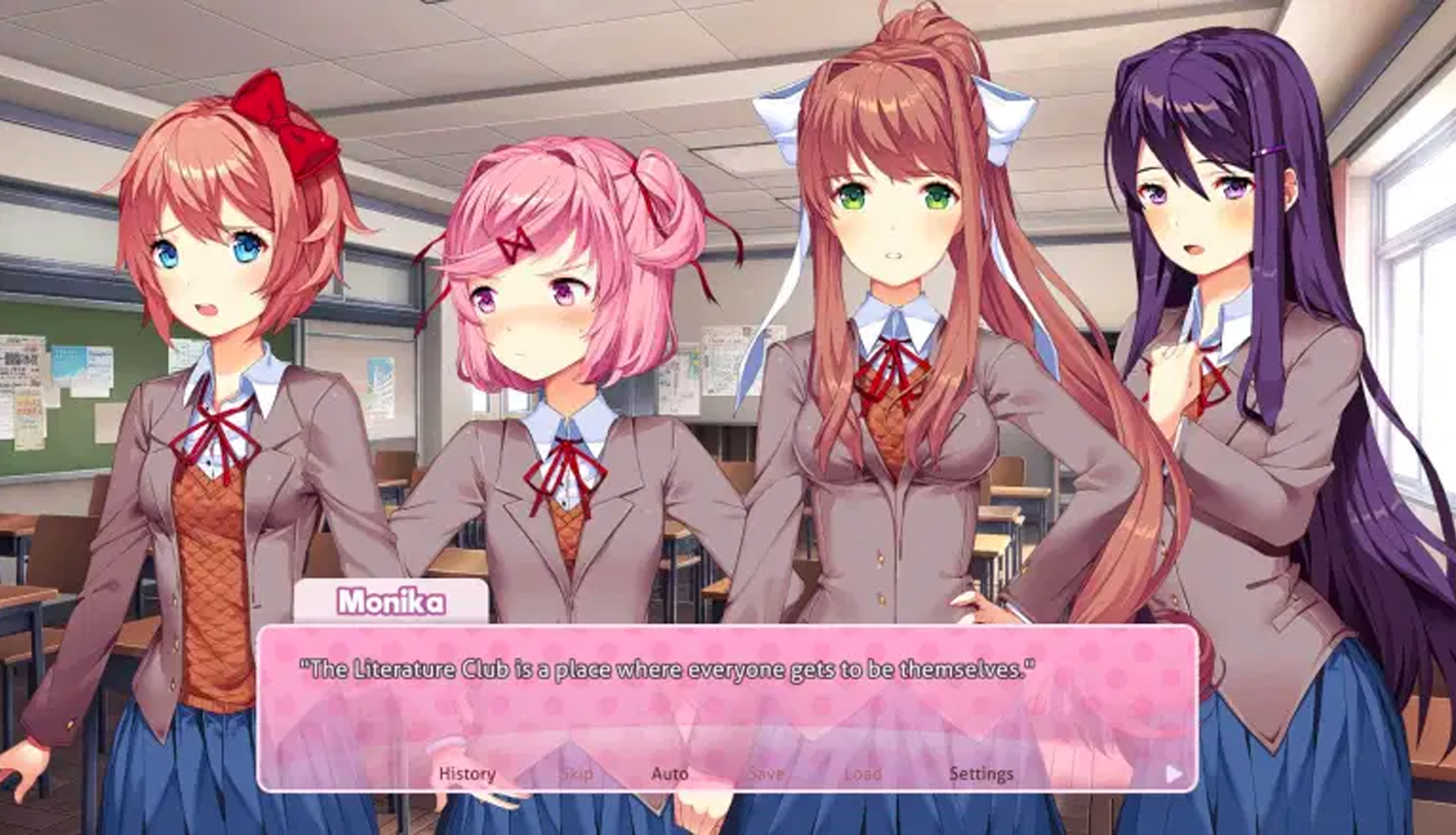

Doki Doki Literature Club (DDLC) is a visual novel game developed by Team Salvato, originally released in 2017. The game follows a student (controlled by the player) as they join their high school’s literature club and meet and interact with the girls that are a part of it—Yuri, Natsuki, his friend Sayori, and club president Monika. While the game resembles (and is intentionally constructed to be) a typical dating simulator at first, as the player progresses, it becomes a psychological horror game that leans heavily into non-linear narrative and breaking the fourth wall. The game is stated as being for mature audiences due to its disturbing and graphic content, and is likely targeted towards those that like horror, as well as non-traditional storytelling. It also likely appeals to those who are somewhat familiar with dating simulators, as it draws on and then breaks the tropes that exist in the genre.

Overall, DDLC intertwines feminist theories through its narrative and its key mechanic of allowing the female characters—especially Monika—an unprecedented amount of self-awareness and agency within the game. However, there are also some critiques that can be made about the game and how it portrays the girls as a result of the way it still incorporates many aspects of traditional dating simulators, even if it’s for the purpose of later subverting them.

In “Play Like a Feminist”, Chess describes that a feminist game is “one that is conversational, personal, and relays narratives that surpass the expectations we tend to have of those ushered in to and for patriarchal audiences”. This idea—that the narrative surpasses what we expect out of it—is perhaps the main way DDLC intertwines feminist theory into itself. The presents itself as a dating simulator, where the player can romantically pursue Yuri, Natsuki, or Sayori. The club president, Monika, at first appears to only be a bystander—the player isn’t given the option to court her. However, as the story progresses, it’s revealed that Monika is self-aware and has the ability to manipulate the game’s code, including changing the actions and the personalities of the other girls in increasingly disturbing ways, which she does in an attempt to stop them and the player from falling in love. Monika also confesses that she herself is in love with the player beyond the fourth wall specifically because they are “real” and not part of the programmed world she knows, and ends up deleting the other girls’ character files. This specific mechanic—of having an internal female character be able to exert such massive influence on the entire game—can be read as highly feminist.

Especially in the realm of dating simulators, where the girls in-game are more or less objects there to fall in love with the protagonist simply because they’ve been coded to, Monika subverting this expectation and taking control of the game—and thus taking control of the player’s experience of the game—is an major inversion of the traditionally patriarchal expectation that Chess describes. She expresses free will—she is obsessively in love with the player because she chooses to be—and perhaps more importantly, has the power and agency to enact it. This also ties into how Chess describes agency in feminism as “the will to act and gain voice in a system of power” and that video games can become important “agentic-training tools”. Here, Monika shows an unprecedented amount of this exact agency. She has the will to act and gain a voice against the system of power that restrains her—the video game code that originally side-lined her as only a supporting character when she wanted to be the romantic interest of the player. She takes control of her situation (though in a highly disturbing and horrific way) and is able to corner the player for herself to an extent.

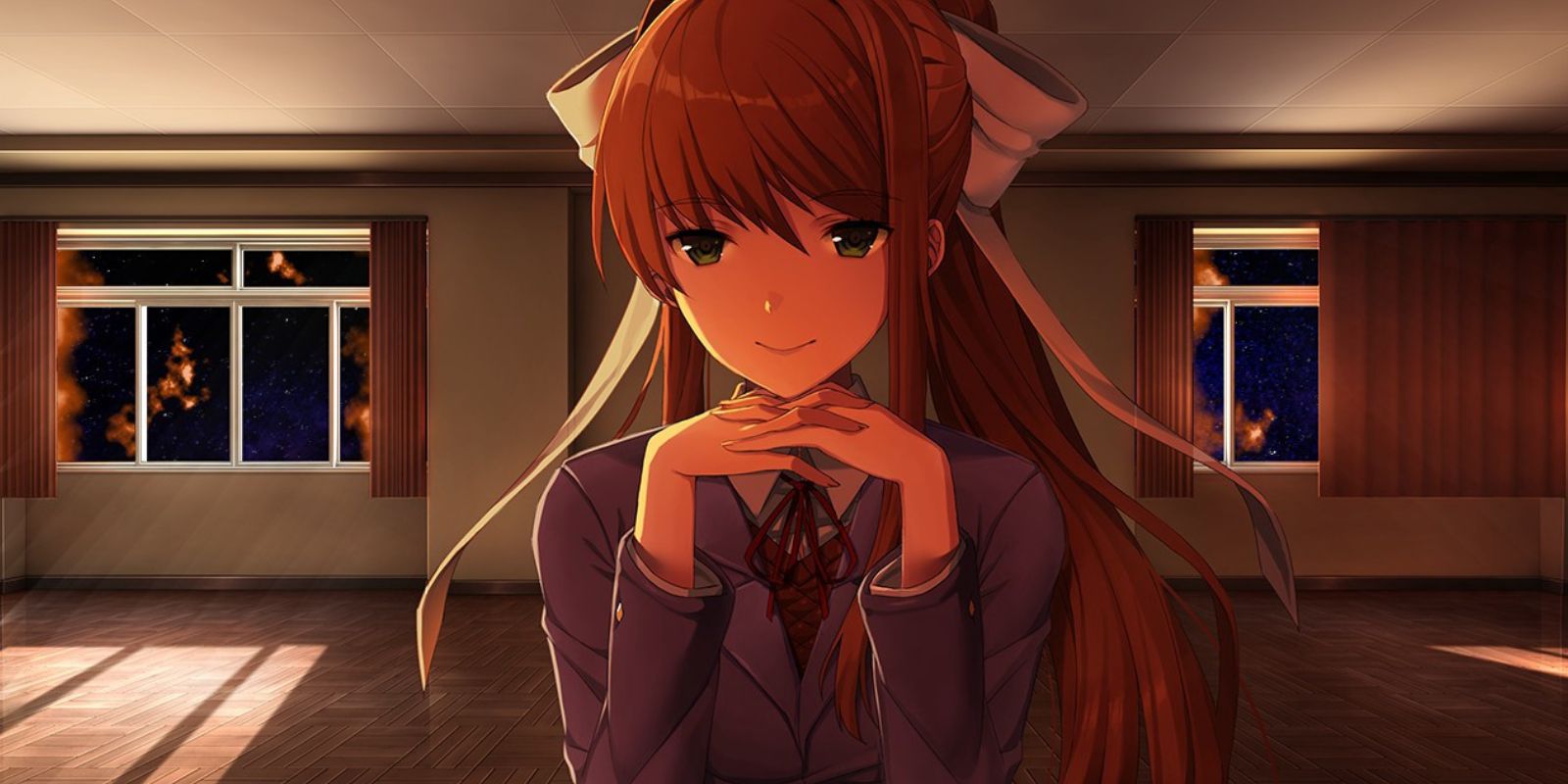

Monika after having deleted the other character files. The player is in this classroom with her indefinitely until they delete her file as well.

Indeed, Chess goes on to say that “often women game players have confided in me that a desire for “control” is a primary drive for certain games”. This time, while it’s not the player that achieves control, it does depict a Monika taking control of her game: DDLC from the “other side”. While the player in the end can “defeat” Monika by manually going into the DDLC directory and deleting her character file, DDLC does a ton to break the expectation of girls and women as bystanders entirely subject to the coded “rules” of the world around them. This particular mechanic of fourth-wall breaking and game corrupting also does a lot to produce the aesthetic of narrative and discovery, creating an intense sense of drama as the player begins to find out the true story and discovers the extent to which the game breaks the fourth wall. When I first played through this game, I was personally fascinated by this particular turn in the story—I never expected that any character in the game would be able to change the course of the game to this extent. The fourth wall breaking was also jarring, but thought-provoking.

However, there are some critiques that can be made of DDLC, mainly due to the way it depicts the female characters’ motivations. The driving force behind most of the female characters in the game is that they are obsessively in love with the male-coded protagonist or the player, and go to great lengths to secure his love and will otherwise self-harm or engage in other destructive behaviors if they do not. While it’s stated in-game that much of this is due to Monika’s manipulation, Monika herself is also driven by obsessive love for the player, and could feed into the stereotype that a woman’s primary focus should be finding and winning over a romantic partner. Yet, it can also be argued that this was unavoidable for DDLC. In order to break the tropes of traditional dating simulators, DDLC had to first set itself up as one—the psychological horror that ensued would not have been possible (or perhaps would’ve otherwise felt strangely motivated or out of character) had the girls not been in love with the protagonist and player.

Overall, DDLC, with its heavy use of breaking the fourth wall and giving its female characters unprecedented agency and control over the story, intertwines feminist theory and can be read as a highly feminist game.

Discussion Question: In order to subvert patriarchal expectations, was it necessary for DDLC to go to the extent it did in building those same expectations into its story and characters? Paradoxically, would the game have had as much of a feminist aspect to it if it didn’t have that baseline to then break?