Game: Among Us

Available Platforms: Cross-platform on Mobile (iOS & Android), PC, Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5, Xbox One, and Xbox Series X/S

Platform Used: Mobile (Android)

Game’s Creator: Innersloth; the idea for the concept was given by Marcus Bromander, co-founder of Innersloth.

Target Audience: General, all ages, although the depictions of cartoon violence may suggest a PG (parental guidance suggested) rating. This game became particularly popular during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown restrictions when people were yearning for social connection. In my opinion, it is the most fun to play with friends while on a voice call to help facilitate voting.

How does the game emphasize social deduction through its mechanics?

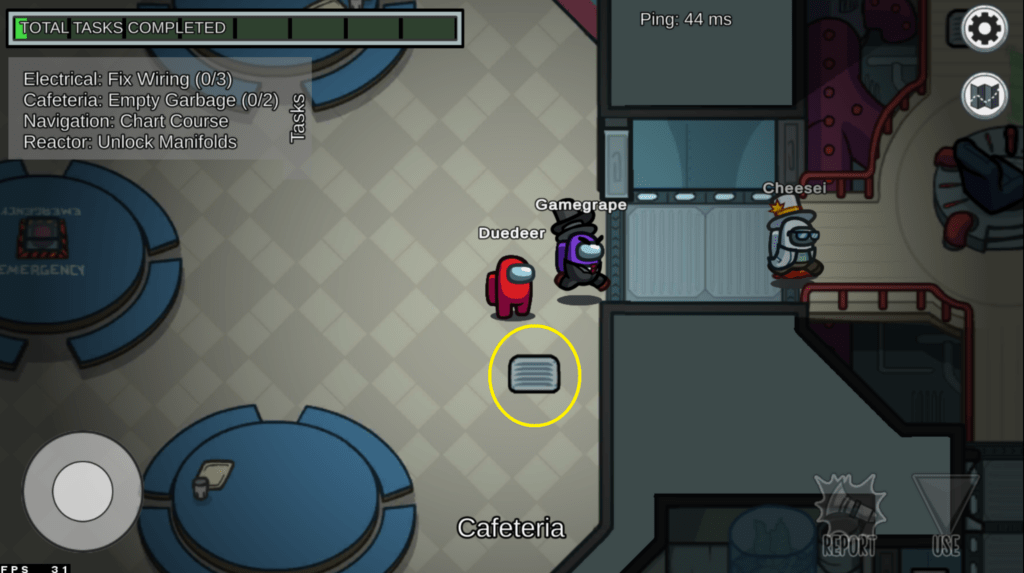

Among Us offers its players consistent windows of deniability that help create chaos among the group trying to argue in favor or against someone’s innocence when deliberating on who are the true imposters in the group. Among Us gameplay commonly relies on unilateral competition between players: the survivors versus the imposters. An example of a window of deniability is the emergency meeting button which can be pressed by either a survivor or an imposter, requiring everyone on the map to meet and optionally vote someone out.

Everyone is only allowed one emergency button press per game. When it is pressed, everyone is made aware of who pressed the button and who is currently dead. Although it may initially seem that the button is meant to help the survivors alert the rest of the group of a new suspicion, potentially allowing them to vote an imposter out before they can commit a murder. However, it is well-known that imposters may hijack this mechanic and attempt to pre-emptively accuse a survivor of foul play if said survivor saw the imposter commit a suspicious act like “venting” and murdering another survivor to remove the eyewitness. “Venting” is when a player travels from one room to another using the map’s ventilation/tunnel system, which is an ability unique to the imposters.

If an emergency meeting is called, there is no verifiable way of determining whether an accusatory button-presser is an imposter or survivor since it becomes a “he said, she said” argument without any additional information introduced by the group to support or deny claims made by the button-presser. Dead players are not given a vote or allowed to speak to their team. Herein, lies the chaos.

Moreover, survivors are given incomplete information. A clever decision made by the game designer to help accomplish this is the physical and administrative separation of tasks throughout the map, requiring the group to split up. The opaque nature of everyone’s specific tasks allows for imposters (who cannot complete tasks) to gaslight the group into believing that they were away from the group to finish the task instead of searching for their next murder target. This is the main environment where players socially deduce who is an imposter and who is a survivor. As it stands, the discussion is mostly text-based which is not ideal due to the time limit present, leading to short, uninformative claims. As a way to enrich the conversation and increase the bandwidth of transferrable information, the game designers may choose to implement a lobby voice chat feature. This decision, however, may introduce the burden of incorporating more moderation safeguards to maintain a welcoming, non-toxic environment, especially for younger players.

Furthermore, when someone works on a task, it takes up a large percentage of the player’s screen, blocking their view of most of the room they might be in, leaving them defenseless and clueless about any surrounding danger.

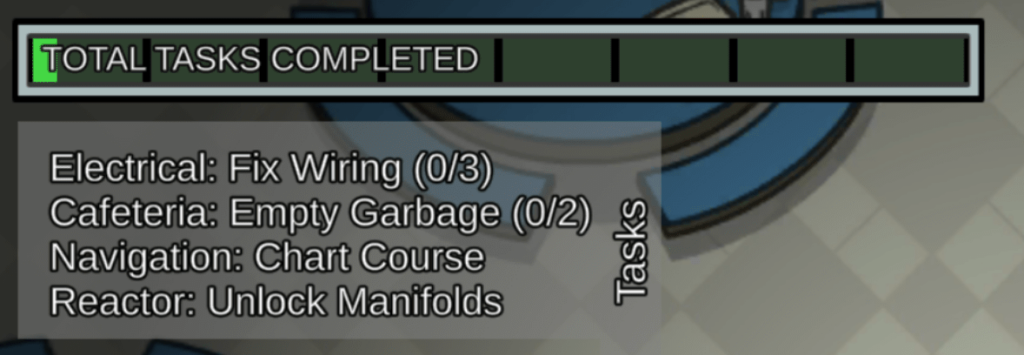

These tasks, apart from being the main objective for the survivors to complete, oftentimes become the subject of discussion since some players may intentionally keep an eye on the task completion bar to see if it changes after a fellow group member “finishes” their task. This strategy seems to be a potential flaw at first, but since the only way to kick someone off (and by extension, “kill” the imposter) is to convince the rest of the group which itself may contain more imposters, the lack of publically-verifiable information puts into question the honesty of each player’s claim of innocence or culpability. Players must consequently outwit everyone else and any attempts at deception. I have come to find Among Us to be a game where players enjoy fun in the social fellowship form.

Nevertheless, if the person who uses this strategy to establish guilt is the deciding vote in kicking an imposter, it may be a mode of gathering information that is inconsistent with the intentions of the game designer. To solve this, the bar’s status may be changed to update at random or consistent periods to help obfuscate when a task is completed from when it is publically marked as done, removing this information leak.